In the icy waters of Antarctica lurks an entire mysterious ecosystem. There, scuttling across the seafloor on spindly little legs, eerie sea spiders make their home.

One known as the giant Antarctic sea spider (Colossendeis megalonyx) has had one of its secrets revealed. Scientists have finally seen the way these curious creatures reproduce – and as far as experts know it’s unlike any other species of sea spider.

“In most sea spiders, the male parent takes care of the babies by carrying them around while they develop,” says marine ecologist Amy Moran of the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa.

“What’s weird is that despite descriptions and research going back over 140 years, no one had ever seen the giant Antarctic sea spiders brooding their young or knew anything about their development.”

In spite of the name, sea spiders are not actually spiders that live in the sea. Nor are they crustaceans, like spider crabs. They are marine arthropods that belong in a group all of their own, known as pantopods, the phylogeny of which has proven surprisingly tricky to classify.

Nevertheless, they are very successful. They can be found in different environments all around the world, including deep and shallow waters, waters of varying salinity, and various temperature ranges.

While we don’t know as much about sea spiders as we do other animals, their reproduction has been pretty well characterized. Once a pair has decided to mate, the male climbs onto the female and they line up the genital pores on their legs. The female releases her eggs; the male fertilizes externally. Then, the female makes an exit while the male stores the eggs on a pair of special legs called ovigers to carefully tend them while they incubate.

Although we’ve known about this particular species of giant Antarctic sea spider since at least 1881, its particular reproductive habits had never before been verified as typical.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” allowfullscreen>

At the end of 2021, Moran and her colleagues made an expedition to Antarctica, to study a phenomenon known as polar gigantism. This is a phenomenon whereby many polar species are much physically larger than their lower-latitude relatives. Sea spiders are no exception: most species of sea spiders are smaller than a fingernail. At the poles, sea spider leg spans can reach 70 centimeters (2.3 feet).

While diving under the ice in McMurdo Sound, some of the team came across giant Antarctic sea spiders that appeared to be mating. So, they gently collected the animals and transferred them to observation tanks to figure out how the heck these enigmatic creatures procreate.

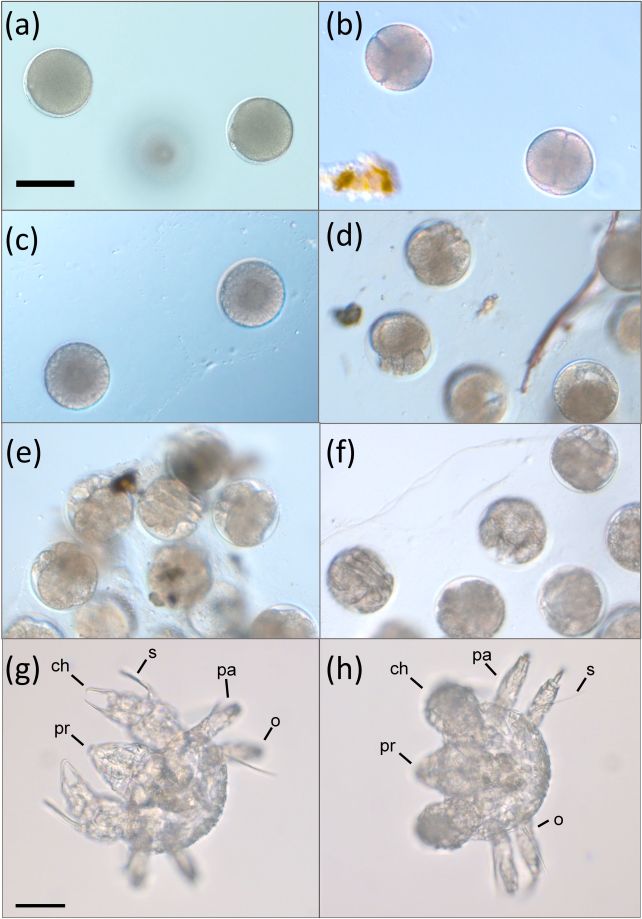

They carefully watched two separate breeding groups, and the results were astonishing. Between them, they produced thousands of eggs, seen as gelatinous clouds that surrounded a single spider that had previously been part of a mating group.

One parent – probably the male – took this cloud of eggs and, over the course of two days, painstakingly glued them to the substrate at the bottom of the tank. There, the eggs developed for several months before hatching tiny little sea spider larvae. The first hatching occurred 8 months after spawning.

Following the observation in the tanks, the researchers spotted similar gelatinous clouds around adult sea spiders several times in the wild. Collection and analysis showed that these, too, were eggs.

So, unlike other sea spiders whose reproductive strategy is known, giant Antarctic sea spiders stash their eggs in rocks on the seafloor to incubate.

The incubation period for many species of sea spider is unknown, but we do know that, for one species in the North Atlantic, Pycnogonum litorale, the period is around 1 to 3 months, at least in a laboratory setting. It’s unknown why the giant Antarctic sea spiders don’t brood their young in the same way as other sea spiders, but the length of incubation may have something to do with it.

Over a matter of weeks the stowed eggs are covered in a carpet of algae, making them effectively invisible. This neatly explains why no one had seen them before – but also suggests that hiding under the algae for periods of at least 8 months might be a safer bet than hanging about on dad’s far more vulnerable legs.

“We were so lucky to be able to see this,” says marine biologist Aaron Toh of the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. “The opportunity to work directly with these amazing animals in Antarctica meant we could learn things no one had ever even guessed.”

The team’s research has been published in Ecology.