A preliminary test on a handful of volunteers suggests our respiratory system can tolerate at least short-term exposure to low concentrations of graphene nanoparticles.

Graphene’s impressive flexibility, exceptional strength and conductive properties mean it has potential in many fields from water filtration to condoms, supercomputers, and medical devices.

Unfortunately we humans have an appalling track record of unintentionally poisoning ourselves and the life around us with our technological breakthroughs. While their uses have undeniably advanced our societies, everythiung from transport to pesticides to plastics has come at a cost to our health and wellbeing.

In an effort to break this habit, researchers from across Europe and the UK have put one of the most promising new materials to a direct health test.

“Nanomaterials such as graphene hold such great promise, but we must ensure they are manufactured in a way that is safe before they can be used more widely in our lives,” says University of Edinburgh’s cardiologist Mark Miller.

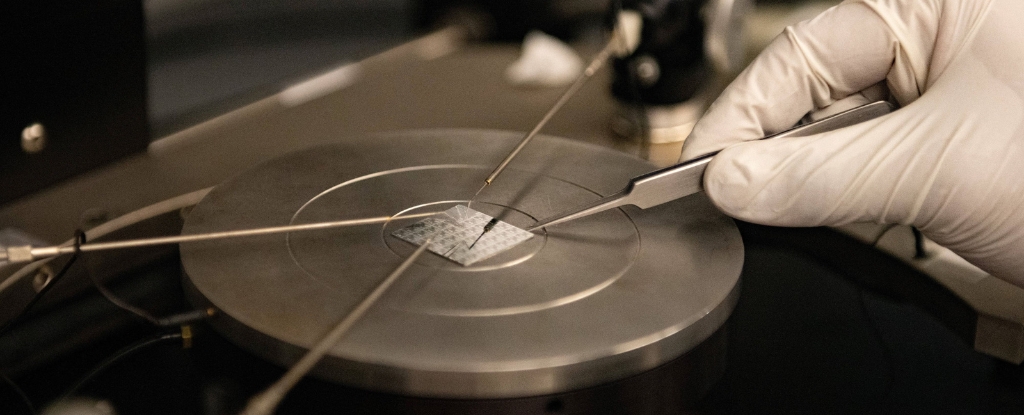

After a decade of laboratory tests on mice and human tissues, University of Edinburgh cardiologist Jack Andrews, Miller, and colleagues recruited 14 volunteers to directly inhale different concentrations of graphene oxide nanoparticles.

Their blood pressure, clotting, and inflammation markers were measured along with lung function before breathing in the particles and every two hours during the exposure. The process was repeated again two weeks later.

The volunteers did not experience any clear changes in their respiratory or cardiovascular systems, nor show signs of inflammation after inhaling the very pure form of graphene oxide. In contrast, similar concentrations of diesel exhaust do produce signs of cardiovascular dysfunction, the researchers explain.

The controlled laboratory environment meant the scientists could eliminate other environmental stressors that can confound results. However, lessons from plastics show some particles react very differently once they’ve interacted with the outside world. What’s more, some of our body’s inflammation pathways take longer to respond than the six hour duration of the study, the researchers point out.

The team did note a small increase in blood clotting when they tested graphene in model of an injured artery outside of the human body. So the tiny nanoparticles, thousands of times thinner than our hairs, may not yet be completely in the clear.

“The findings… lay the foundations for future investigations to establish which properties of graphene materials determine their biological actions,” the team writes in their paper, explaining this is only a starting point for establishing this material’s safety limits.

Next, they’re keen to test different forms of graphene and longer-term exposures.

“Being able to explore the safety of this unique material in human volunteers is a huge step forward in our understanding of how graphene could affect the body,” says Miller.

“With careful design we can safely make the most of nanotechnology.”

This research was published in Nature Nanotechnology.