Last year Earth warmed around 0.2 °C more than climate models predicted. While that may not seem like much in isolation, when you consider it’s a measure across an entire planet it amounts to a heck of a lot of unexplained heat.

“It’s humbling, and a bit worrying, to admit that no year has confounded climate scientists’ predictive capabilities more than 2023 has,” writes NASA climatologist Gavin Schmidt in an article for Nature.

“The 2023 temperature anomaly has come out of the blue, revealing an unprecedented knowledge gap perhaps for the first time since about 40 years ago, when satellite data began offering modellers an unparalleled, real-time view of Earth’s climate system.”

Schmidt warns if this unexplained anomaly doesn’t settle by August, in line with previous El Niño fluctuations, then we will be in uncharted territory.

Several theories have been posed for the excess heat beyond what is expected from the El Niño and known rates of increasing CO2. These include a decrease in surface-cooling aerosols from shipping after regulation changes in 2020; an increase in heat-trapping water vapor from the 2022 eruption of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai; and peak activity in the current solar cycle sending more heat our way.

But even combined these all don’t fully account for observed extra heat, Schmidt argues.

The concern is we’re missing something critical in our understanding of Earth’s climate systems, that would explain an accelerated rate of warming, such as a potential miscalibration in the start date of humanity’s impact on the climate.

Being ahead of schedule would explain why extreme climate consequences, including deadly floods, fires, and storms, have been whacking us so hard and fast already.

“It could imply that a warming planet is already fundamentally altering how the climate system operates, much sooner than scientists had anticipated,” explains Schmidt.

Yet the sudden jump in heat may still be a short-term anomaly or ‘blip’ in the data, Schmidt concedes.

“There is a risk of conflating shorter-term climate variability with longer-term changes,” Berkeley Earth climate scientist Zeke Hausfather cautions in an analysis for Carbon Brief.

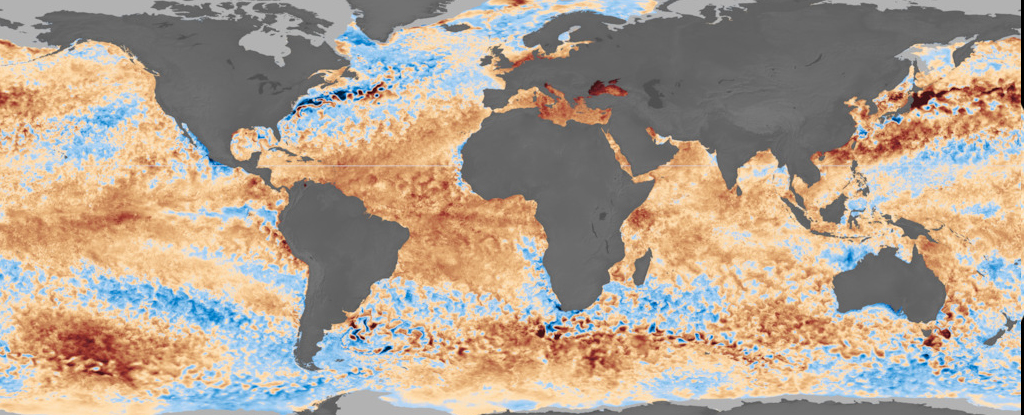

However, Hausfather also notes, there are some early signs that this may be more than a temporary anomaly, including accelerated warming recorded in ocean heat and satellite measurements of Earth’s energy imbalance.

What’s more, there’s also no sign of this sharp increase in climate indicators changing course. We’ve just hit the 10th straight month of record global heat, with 12 months now above the Paris Agreement’s pledge of keeping the average global temperature below 1.5 °C of warming.

While researchers probe and debate the numbers (exactly as scientists should!) we’re experiencing and witnessing the very real consequences of this excess heat all around us.

Three-quarters of the world’s largest coral reef system, the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, is currently suffering high to extreme levels of bleaching. Animals are dying en masse and millions of people are going hungry as climate change drives famine in Africa.

This is only the beginning. Some places are already feeling the heat far more than others.

While it is important to work out these potentially large uncertainties in climate modeling, a greater priority is making substantial progress towards stopping the greenhouse gas emissions that drive the bulk of global warming.