The presence of parasitic microbes has for the first time been found literally altering the metabolism of their hosts.

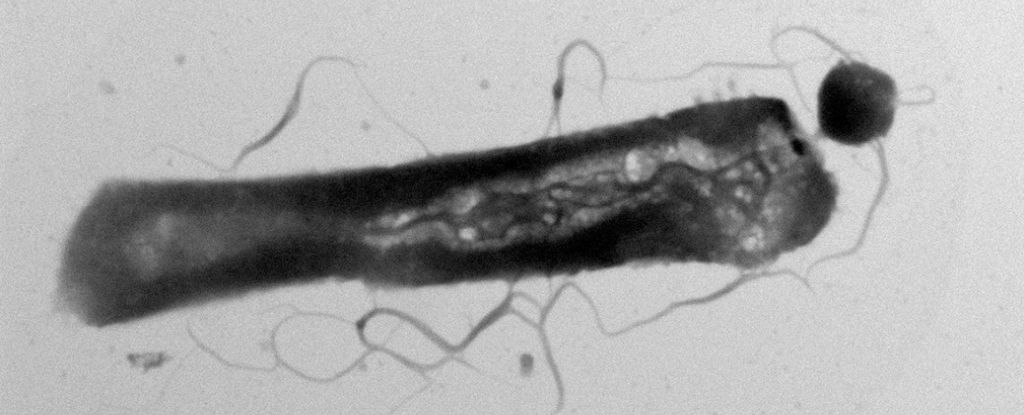

The culprits are tiny, parasitic archaea of the species Candidatus Nanohaloarchaeum antarcticus that parasitize other single-celled organisms, the host archaeon species Halorubrum lacusprofundi.

And researchers have found that these parasites are very selective about the resources they steal from the body of their host.

“In other words,” says marine microbiologist Joshua Hamm of the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ), “Ca. N. antarcticus is a picky eater.”

Archaea are single-celled organisms that are similar to bacteria, but belong to an entirely different domain of organisms. Ca. N. antarcticus belongs to a group of archaea known as DPANN – small archaea. Some of these parasitize other single-celled organisms, slurping up their hosts’ lipids as building materials for their own membranes.

A few years ago, a team of scientists found that Ca. N. antarcticus doesn’t just parasitize any old microbe – it’s specifically, and surprisingly, reliant on H. lacusprofundi for lipids and other metabolites that it can’t make itself.

Led by NIOZ microbiologist Su Ding, a team of researchers took a much closer look at both organisms to better understand Ca. N. antarcticus’ dependency. Their work involved analyzing the lipids, or fatty compounds, found both in host-parasite pairs, and in H. lacusprofundi that have not been parasitized by Ca. N. antarcticus.

This was only possible using a new analytical technique developed by Ding that allowed the researchers to see all the lipids present, even lipids they hadn’t yet identified. Previous techniques only allowed scientists to see lipids if they knew what they were looking for.

Their findings were surprising. Firstly, the parasites analyzed didn’t slurp all the lipids willy-nilly from their hosts. They were found to be selectively taking only certain compounds for their own use, and leaving the rest untouched. Picky eaters indeed.

Secondly, the metabolism of H. lacusprofundi shows marked differences between parasitized and non-parasitized individuals. The quantities of the lipids present differ for a parasitized microbe, with a significant depletion in the lipids taken by Ca. N. antarcticus, but an increase in other lipids in the host’s tiny body.

The researchers say this is likely a response to the increased metabolic load generated by the parasite’s presence. In addition, the host species has an unusual membrane for archaea. While it provides H. lacusprofundi with an ecological advantage in terms of being more energy-efficient, it may also allow the parasite to get away with its fussy taste in fats.

The researchers also noted that some of the changes in infected hosts’ membrane composition may be a defensive response to the parasite.

Further research will be required to understand the mechanisms behind both the parasite’s selection of lipids, and the host’s defensive response, but just knowing that a parasitic archaeon can change its host’s metabolism has some interesting implications.

Bolstering defenses and altering lipid production in response to a parasite, the researchers say, could have implications for how the host responds to other external influences, such as changing temperatures or acidity levels.

“Not only does [the discovery] shed a first light on the interactions between different archaea; it gives a totally new insight in the fundamentals of microbial ecology,” Hamm says.

“Especially that we’ve now demonstrated that these parasitic microbes can affect the metabolism of other microbes, which in turn could alter how they can respond to their environment. Future work is needed to determine to what extent this may impact the stability of the microbial community in changing conditions.”

The team’s research has been published in Nature Communications.