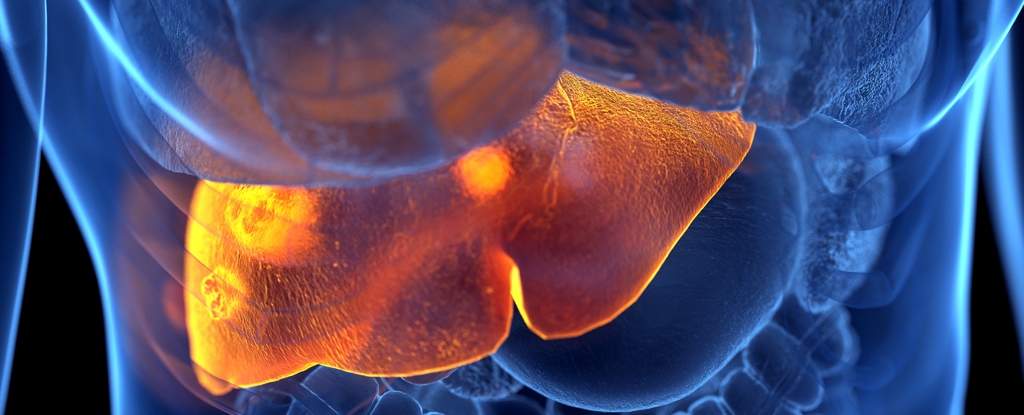

Giving meat a miss for just one meal reduces harmful ammonia buildup in people with late stage liver disease, according to a small clinical trial in the US. The findings suggest that even small dietary interventions could help these patients avoid serious complications.

Ammonia is highly toxic, especially if it reaches our brains, but it’s also the natural byproduct of protein digestion in the human body, a normal waste product we’re usually equipped to deal with.

In a healthy person, ammonia is released from our food by bacteria in the intestines as they break down proteins. It passes into the liver which converts it to a less toxic form, urea, which is disposed of in urine.

Foods high in protein – especially those from animal sources – are usually considered part of a healthy diet, but this new study suggests that moderating meat intake might ease the load on people with cirrhosis, the most advanced stage of liver disease.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

The more meat you consume, the more ammonia your liver has to process, and an already damaged liver will inevitably struggle to get the job done. This leads to a backlog of ammonia in the blood, which is linked to hepatic encephalopathy (HE), a type of cognitive decline.

The onset of HE can be gradual or sudden with liver failure and can sometimes lead to coma, where swelling of brain tissue can be fatal. This new research suggests a seemingly simple way for people with cirrhosis to dodge these concerning flow-on effects, by going straight to the source.

Thirty male outpatients with cirrhosis treated at the Richmond Veterans Affairs Medical Center participated in the study, though not all participants were veterans. All were habitual meat-eaters with similar Western-style diets and had similar gut bacteria profiles before the experiment. Half of them had prior HE.

The patients were split into three groups, each given a different kind of burger at mealtime. All burgers contained exactly 20 grams of protein: pork/beef burgers for the first group, a vegan meat substitute for the second group, and a vegetarian bean burger for the third. All burgers were served with whole grain buns, low-fat potato chips, and water – no extras allowed, no supersize.

As much as possible, the only main difference between groups was the protein source on their burgers. But that difference had a measurable effect, according to the analysis of their blood samples taken before and after the meal.

Blood serum ammonia levels were significantly elevated for patients in the meat burger group, compared with the other two groups and all patients’ baseline levels before the meal.

Patients with prior HE had higher blood serum ammonia levels across the board, but those in the meat group also showed the post-burger spike within one hour of eating, a trend unique to their group.

“It was exciting to see that even small changes in your diet, like having one meal without meat once in a while, could benefit your liver by lowering harmful ammonia levels in patients with cirrhosis,” says gastroenterologist Jasmohan Bajaj from Virginia Commonwealth University.

“Liver patients with cirrhosis should know that making positive changes in their diet doesn’t have to be overwhelming or difficult.”

While the study is preliminary and the measurements were taken after just one meal, the team is confident enough in the results to suggest that physicians start implementing them by encouraging their meat-eating liver disease patients to incorporate plant-based alternatives into their diets.

We know from other research that eating less meat and more vegetables is linked to longer, healthier lives with a lower risk of cancer. It’s also good for the planet.

The researchers think the next step is to conduct longer-term studies on the effects of similar diet changes on patients with cirrhosis.

“We now need more research to learn if consuming meals without meat goes beyond reducing ammonia to preventing problems in brain function and liver disease progression,” says Bajaj.

This research is published in Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology.