Vaccination saves lives – an astounding 154 million of them since 1974 when the World Health Organization (WHO) launched its expanded global immunization programme, according to new research.

The goal of the programme was to make vaccines available to all children, and while there are enduring challenges in that regard, the upshot is abundantly clear in the multitude of deaths that were averted in the past 50 years, the vast majority of which children under 5.

“We also discovered that measles vaccination accounted for 60 percent of the total benefit of vaccination over the 50-year period, which was also the greatest driver of lives saved,” says Andrew Shattock, an infectious disease modeler at the Telethon Kids Institute in Australia, who led the study.

The findings are a timely reminder of just how well vaccination works, protecting not only the vaccinated but also the most vulnerable within our communities, including young children, the elderly, and immunocompromised people from infectious diseases.

But that protection only goes so far. Just months ago, experts warned that the US was close to reaching a dangerous tipping point where vaccination rates had dropped so low that unvaccinated people were no longer necessarily protected by the vaccinated community, which could lead to otherwise preventable deaths.

Global trends are similarly concerning. A record number of children weren’t vaccinated against measles in 2021, leading to numerous outbreaks of the infectious disease around the world in subsequent years, including the US – a country that had eliminated the disease in 2000.

Experts suggest vaccine complacency and apathy, rather than hesitancy, have been driving factors behind the precipitous decline in vaccination rates.

Part of the problem might be that when vaccines work to prevent disease, we see fewer cases and outbreaks, removing the most emotive reminders of the risks of failing to vaccinate populations. As the saying goes, vaccines are victims of their own success.

Smallpox was the first and only infectious disease to have been globally eradicated with vaccines, with the last known natural case in 1977.

In more recent memory, WHO said in 2023 that vaccination programmes were on the brink of eradicating wild poliovirus from Afghanistan and Pakistan, the two countries in which polio is still endemic, but challenges remain.

Earlier this year, a study revealed that no cases of cervical cancer have been detected in Scotland in anyone who received the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine when they were teenagers – putting the country on track to eliminate cervical cancer in young women.

Acknowledging the known but rare side effects of vaccination, the effort of population-wide vaccination is clearly worth it. The new study from Shattock and colleagues adds to that evidence, showing how on the whole kids live longer when vaccination programs reach them.

Vaccination accounted for 40 percent of the observed decline in global infant mortality, the researchers found, with other likely contributors including improved sanitation, healthcare, and access to clean drinking water.

“In 2024, a child at any age under 10 years is 40 percent more likely to survive to their next birthday thanks to vaccination efforts over the past 50 years,” Shattock says.

The WHO-funded study also found that for every life saved with vaccines, an average of 66 years of full health were gained, translating to a whopping total of 10.2 billion years of health that would have otherwise been stolen by childhood deaths.

If you’re one of those lucky ones living well into adulthood, yet need another reason to stay up to date with your vaccinations, look no further: Multiple studies have recently underscored the link between viral infections, such as influenza and shingles – for which vaccines are available – and the risk of developing dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease.

While vaccines won’t prevent all infections, they can dramatically reduce the severity of illness and your chances of hospitalization – which in turn, may potentially help prevent neurodegenerative disease.

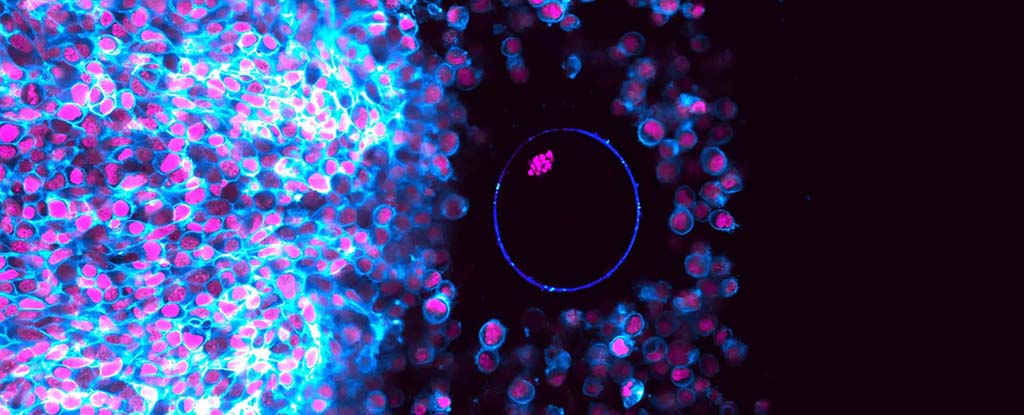

Meanwhile, researchers are hard at work improving their techniques for developing vaccines and experimenting with new vaccine technologies to protect us against even more infectious diseases and cancers, too.

The research has been published in The Lancet.