Last week, Earth was treated to a rare event: not one, but two large asteroids, passing by within hailing distance.

Neither 2024 MK nor 2011 UL21, as the asteroids are named, came close enough to pose a hazard, but both were within range of radar imaging systems. So NASA got a few happy snaps to mark the occasion.

These are more than just asteroid flyby souvenirs. Scientists can study the images to understand the properties of the rocks that can be found in Earth’s vicinity – information that can help us put together strategies for any future asteroids that might one day threaten our planet.

Earth’s little corner of the Solar System is mostly empty, but not completely. The occasional comet or asteroid sails by as it makes its own looping orbit around the Sun.

The vast majority of these are not going to be a problem. But anything that passes within a certain distance of Earth, or is above a certain brightness, is classified as potentially hazardous.

That’s because, even though their current path might be fine, something unexpected could happen, such as a collision with another object that knocks it onto a collision course with Earth. It’s not probable, but also not impossible.

Both 2024 MK and 2011 UL21 were in the potentially hazardous category; luckily for us, no unforeseen wackiness knocked them off course in our direction.

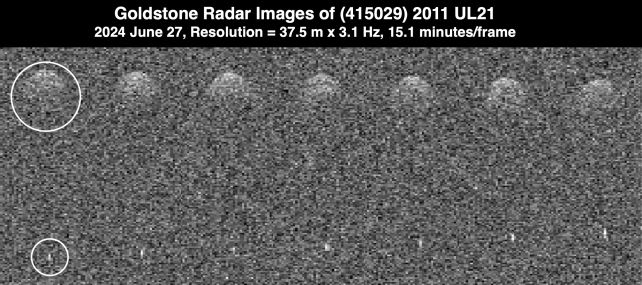

2011 UL21 flew past Earth on June 27, at a distance of 6.6 million kilometers (4.1 million miles), about 17 times the distance between Earth and the Moon.

Then, less than two days later, 2024 MK made an appearance. On June 29, it flew past at a minimum distance of 295,000 kilometers (184,000 miles). That’s much closer, about three quarters of the distance between Earth and Moon.

Imaging such objects isn’t exactly easy, even when they’re relatively close and classified as “large” asteroids. They’re still pretty small in the scheme of things, and not very bright.

That’s why NASA uses a large radar telescope to transmit radio waves into space, and receive the return signal from which scientists can construct images.

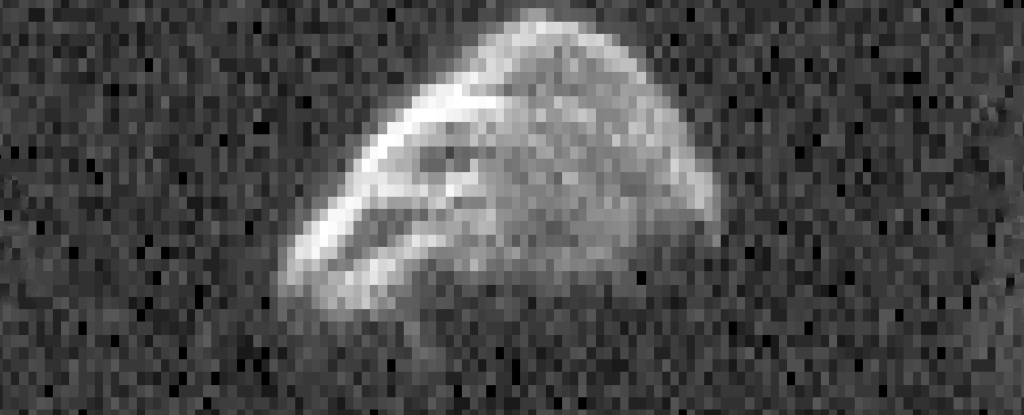

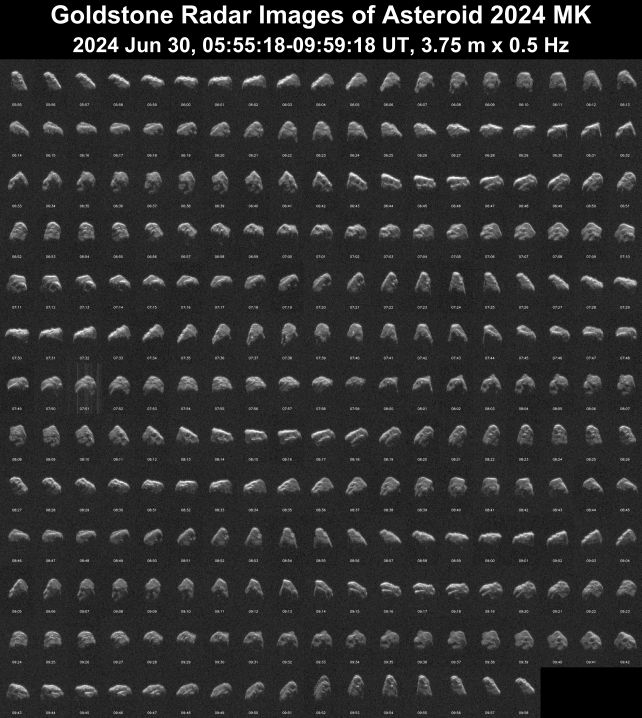

Because 2024 MK was a lot closer – such proximity for an asteroid flyby only occurs every few decades or so – we were able to get much more detailed images.

NASA used one telescope to transmit the radio waves, and a second one to receive them, resulting in images of 2024 MK that include not just the shape of the asteroid, but bumps, divots, boulders, and ridges.

It measures roughly 150 meters (500 feet) across, and has an elongated shape with lots of flat planes. It tumbles as it moves through space, too.

It was only discovered on June 16, and its orbital path was altered by Earth’s gravity, so the observations allow scientists to figure out what 2024 MK is going to do in the future. They revealed that for the foreseeable future, it’s going to safely stay out of our way. Phew.

“This was an extraordinary opportunity to investigate the physical properties and obtain detailed images of a near-Earth asteroid,” says astronomer Lance Benner of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

2011 UL21, at its much greater distance, didn’t return images that were as detailed… but those images did include a little surprise. There, accompanying the 1.5-kilometer-wide asteroid, astronomers spotted a tiny moonlet, at an orbital distance of around 3 kilometers.

This is something we’re finding more and more with large asteroids, actually.

Last year, asteroid Dinkinesh, an object in the asteroid belt visited by the NASA Lucy probe, was discovered to have a little moon. And NASA’s famous Double Asteroid Redirection Test, in which a spacecraft was smashed into an asteroid, was performed on Dimorphos, the smaller of a binary asteroid pair.

We’re finding more binary asteroids because our imaging capabilities are improving, and this is excellent news for planetary defense, and our understanding of Solar System evolution.

“It is thought that about two-thirds of asteroids of this size are binary systems,” Benner says, “and their discovery is particularly important because we can use measurements of their relative positions to estimate their mutual orbits, masses, and densities, which provide key information about how they may have formed.”

And they’re just so gosh-danged cute. Hey there, lil buddy. Fly by any time.