When famed 17th century Renaissance astronomer Tycho Brahe wasn’t gazing at the stars, he turned his hand to deciphering the makeup of matter here on Earth. The exact nature of his chemistry, however, has remained something of a mystery.

A team of researchers from the University of Southern Denmark and the National Museum of Denmark carried out an analysis of a handful of glass and ceramic shards recovered from Brahe’s lab 35 years ago, identifying clues on what his alchemy studies may have entailed.

On four of the five shards, enriched levels of several trace elements were found: nickel, copper, zinc, tin, antimony, tungsten, gold, mercury, and lead. It suggests these elements, including the gold and mercury often used by alchemists to treat diseases, featured heavily in Brahe’s experiments.

“Most intriguing are the elements found in higher concentrations than expected – indicating enrichment and providing insight into the substances used in Tycho Brahe’s alchemical laboratory,” says physicist and chemist Kaare Lund Rasmussen from the University of Southern Denmark.

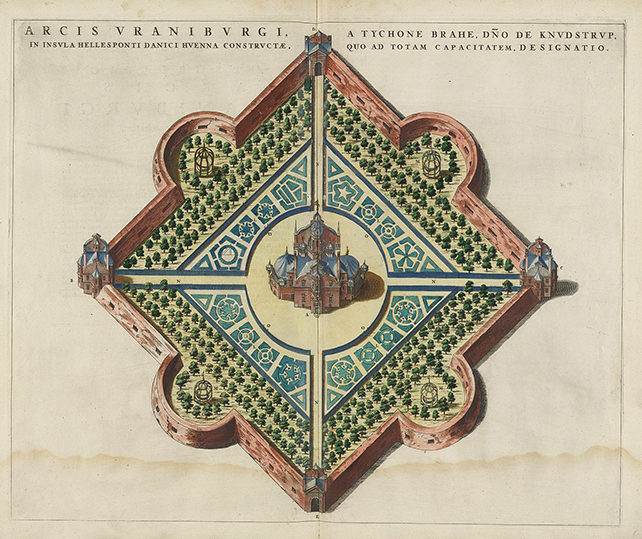

Mass spectrometry was adapted for the chemical analysis, where sample molecules are converted into charged ions to figure out their composition – giving us clues as to what went on in Brahe’s state-of-the-art underground lab, on the now-Swedish island of Ven.

The most intriguing discovery here is the presence of tungsten. It wasn’t actually identified as an element until 1781, so what was it being used for in a lab that was demolished almost 200 years prior?

It may have been incidentally separated from a mineral without Brahe understanding its uncharacterized nature. Alternatively, it’s possible that the scientist was building on the work of German mineralogist Georgius Agricola, who had previously made the first steps towards identifying tungsten in tin ore.

“Maybe Tycho Brahe had heard about this and thus knew of tungsten’s existence,” says Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

“But this is not something we know or can say based on the analyses I have done. It is merely a possible theoretical explanation for why we find tungsten in the samples.”

Brahe lived in an age where sharing experimental knowledge wasn’t necessarily the norm, especially in the field of alchemy. Brahe only told a select number of people about this part of his research, but we know he was working on developing medicines for diseases such as plague, syphilis, leprosy, and fever.

Like many of his contemporaries, Brahe believed in the correspondence of the heavens, Earth, and the human body – so, for example, the Sun, gold, and the heart shared common features. Indeed, an earlier study of Brahe’s remains suggested that he may have taken gold as a form of medicine himself.

“It may seem strange that Tycho Brahe was involved in both astronomy and alchemy, but when one understands his worldview, it makes sense,” says museum curator Poul Grinder-Hansen, from the National Museum of Denmark.

The research has been published in Heritage Science.