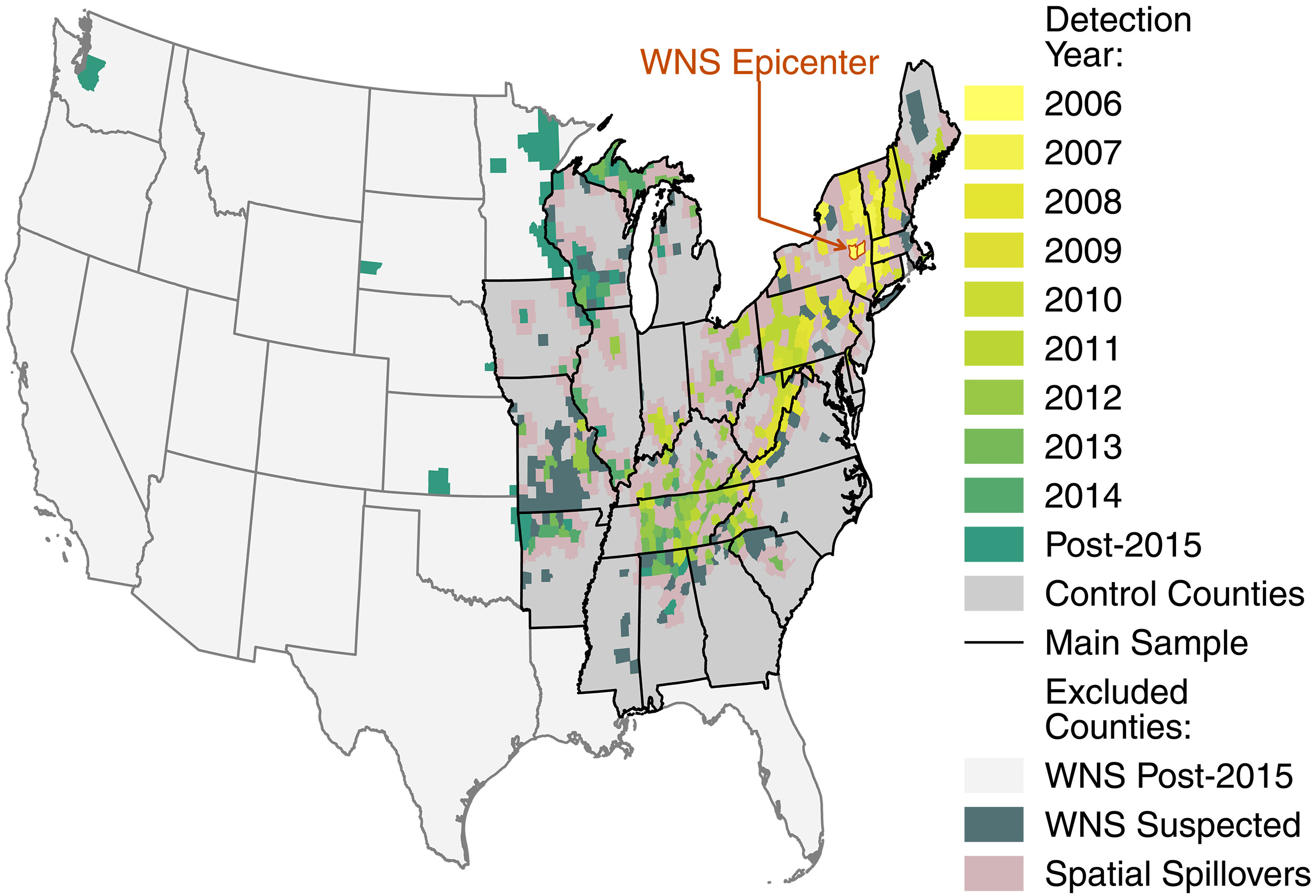

In 2006, people found bats in New York’s Howe Cave that had a peculiar, fuzzy white substance growing on their snouts.

This was the first sighting of white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that has devastated bat populations across the US.

Now, a new study has found more than 1,000 human infant deaths resulted from the loss of bats in North America – which led to increased pesticide use, a grim reminder of how vital this much-maligned mammal is to our wellbeing.

“Bats have gained a bad reputation as being something to fear, especially after reports of a possible linkage with the origins [of] COVID-19,” says the study’s author Eyal Frank, an ecological economist at the University of Chicago.

“But bats do add value to society in their role as natural pesticides, and this study shows that their decline can be harmful to humans.”

White-nose syndrome (WNS) is caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, which grows around the bats’ mouths, noses, and ears.

Frank used quasi-experimental, observational methods to explore how, in the wake of a mass die-off of bats due to WNS, pesticide use increased along with infant mortality.

Insect-eating bats keep crop pest numbers in check, so with bat mortality rates from WNS averaging above 70 percent in the US since the disease was first detected in 2006, farmers were forced to compensate by turning to chemical solutions to protect crops.

Frank addressed both the economic and health costs of this shift, comparing the impacts of pesticide use in counties where WNS caused mass bat die-offs, with counties that were seemingly unaffected.

Counties affected by bat die-offs, he found, increased pesticide use by around 31 percent. Meanwhile, crop sales revenue dropped by nearly 29 percent.

“This demonstrates the substitution between a declining natural input and a human-made input – providing the first empirical validation of a fundamental theoretical prediction in environmental economics,” Frank writes.

He estimates the combined cost to farmers in communities affected by bat die-offs was US$26.9 billion between 2006 and 2017.

And in those same counties, infant mortality rates due to internal causes of death rose by 8 percent. That translates to around 1,334 additional infant deaths, which Frank shows were likely a result of the increased use of pesticides in WNS-affected counties.

In the context of the staggered expansion of the wildlife disease, Frank found these results could be interpreted as causal.

“Any additional alternative explanation would need to change along the expansion path of the wildlife disease around the same timing of its expansion,” he writes.

In additional analyses, he demonstrated that changes in crop composition, other mortality types, or economic conditions could not explain the observed results.

“When bats are no longer there to do their job in controlling insects, the costs to society are very large – but the cost of conserving bat populations is likely smaller,” says Frank.

“More broadly, this study shows that wildlife adds value to society, and we need to better understand that value in order to inform policies to protect them.”

This research is published in Science.