Long before we knew that birds could “see” the Earth’s magnetic field, Albert Einstein discussed the possibility of animals with supersenses in his fan mail to fellow researchers.

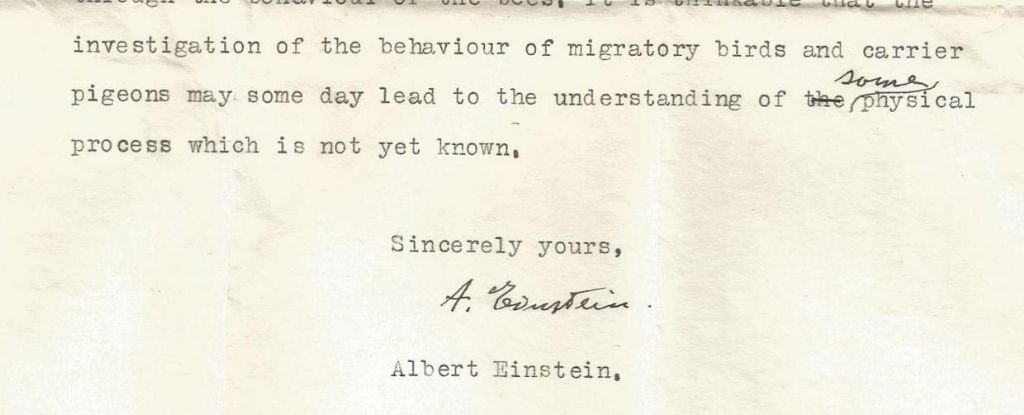

A long-lost letter from the scientist to an inquiring engineer in 1949 turned out to be extraordinarily forward-looking in the fields of biology and physics.

The original question from engineer Glyn Davys that started the correspondence has since been lost, but judging by Einstein’s answer, Davys’ question had something to do with animal perception and what it can tell us about the physical world.

“It is conceivable that the study of the behavior of migratory birds and carrier pigeons will one day lead to an understanding of an as yet unknown physical process,” Einstein wrote in his reply.

More than 70 years later, we now know that Einstein’s hunch was correct. Evidence now suggests birds can do this perceive the earth’s magnetic field with special photoreceptors in their eyes that are sensitive to subtle shifts in the planet’s magnetic field. This allows them to travel thousands of kilometers without getting lost.

Other animals, like sea turtles, dogsAnd beesalso demonstrate an uncanny ability to sense our planet’s magnetic fields, though not necessarily through the eyes.

“That is amazing [Einstein] conceived of this possibility decades before empirical evidence showed that several animals could actually sense magnetic fields and use such information for navigation,” wrote Researchers at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 2021, where the letter was donated.

Still, the Nobel laureate had some clues to guide his thinking. At the time the letter was written, life science and physics were beginning to merge like never before. had bat echolocation recently discoveredand radar technology began to take hold.

In fact, Davys was a researcher in the field himself, which is probably why he was interested in other strange animal senses, like those of bees.

He found a like-minded person in Einstein. It seems that the famous physicist was also fascinated by biological science as a window into unseen physical forces.

His reply letter, which remained undiscovered until Davy’s death in 2011, is brief but confirms that Einstein was similarly fascinated by the behavior of bees.

(Dyer et al., J Comp Physiol A2021)

In the typed note, Einstein admits that he is well acquainted with Karl von Frisch, who recently discovered that bees use the polarization patterns of light to navigate.

It is known that Einstein attended one of Frisch’s lectures at Princeton University six months before the letter was sent. He even had a face-to-face meeting with the researcher, and those interactions clearly made an impression.

While Davys seems most interested in how this new biological knowledge can inform future technologies, Einstein argues that we need more biological research.

“I see no way to use these results for studying the fundamentals of physics,” he replied to Davys.

“This could only be the case if the behavior of the bees opens up a new type of sensory perception or its stimuli”.

Since the letter was sent, we’ve learned a lot about bee behavior and how these curious insects perceive the world. As Einstein predicted, this knowledge is already helping us to improve technology, like the cameras on our iPhones.

However, despite decades of research, there are still many mysteries. The exact mechanisms by which animals perceive light or sense the Earth’s magnetic field are still being pulled apart, and it may not be the same for every species.

Bees, for example, seem to sense this magnetic field in her stomachwhile birds and dogs appear to do this primarily via special photoreceptors in their eyes called cryptochromes.

Even human cells make cryptochromes, and recent research shows that these cells respond dynamically to changes in the magnetic field.

That’s ironic, because that’s what you would expect from a unique quantum reaction. For a photoreceptor to sense a magnetic field, electrons would need to be entangled within the cell, and Einstein dismissed that idea at the time, calling it “spooky action at a distance.”

Einstein wasn’t always right, of course, but even when it came to areas of science outside his area of expertise, the man was smart.

The study was published in Journal of Comparative Physiology A.

A version of this article was first published in May 2021.