One of the most beautiful sights in the summer twilight is the gentle glow of fireflies lighting up the crepuscular gloom.

These twinkling insects are the most abundant bioluminescent beetles, with roughly 2,500 species known around the world. Their glowing abdomens serve multiple purposes – but what we don’t really have a good handle on is how this trait evolved.

According to a team led by paleontologist Chenyang Cai of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, a firefly magnificently preserved for eons in golden amber may have some answers.

Some 99 million years ago, Flammarionella hehaikuni was already lighting up the dusk, suggesting its ancestors had well-and-truly evolved their characteristic glowing butt by the Mesozoic.

It’s the second such Mesozoic firefly found preserved in Myanmar amber. The first, Protoluciola albertalleni, also had a beautifully preserved firefly lantern. And a bioluminescent beetle from a different family was also found in the same amber deposit.

What makes the new discovery so exciting is that the trapped specimen’s lantern is different from the lanterns seen in its amber-trapped contemporaries, showing that by 99 million years ago, insect bioluminescence was already well developed and diverse.

Bioluminescence in fireflies seems to serve two main functions – attracting other fireflies for courtship, and warning predators about any lucibufagin toxins they may be loaded with. Scientists have recently argued, however, that bioluminescence emerged in fireflies before lucibufagins did, which raises some questions about the early benefits of insect bioluminescence.

Cai and his colleagues found their firefly in amber in Kachin State in northern Myanmar, the same region from which the other Mesozoic light-up insects hailed.

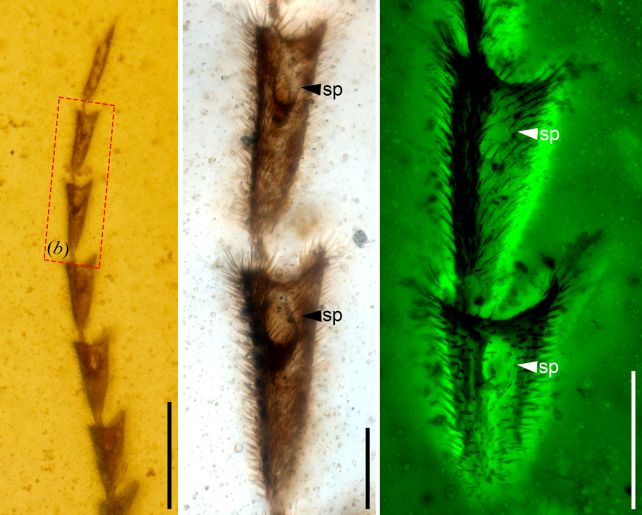

The amber itself is remarkably clear, revealing the insect in exquisite detail. Based on its physical characteristics, the researchers were able to identify the specimen as a female belonging to Luciolinae – one of the largest subfamilies of fireflies, whose members possess flashing lanterns in their abdomens.

But there are some differences. The antennae of Flammarionella (named for French astronomer Camille Flammarion) are densely covered in hair-like appendages called setae, with deep, oval-shaped indentations on many of its segments.

Although we’ve never seen this characteristic in living fireflies, similar features can be found in other bugs. Related to the insect’s sense of smell, the indentations maximize surface area and aid recognition of sex pheromones. Male fireflies often have wackier antennae than females of their species, so finding a male Flammarionella would help us better understand these features.

The fossilized specimen’s lantern is also unmistakable, comprising two segments at the end of the insect’s abdomen. A comparison with other species of Mesozoic bioluminescent insects may, hopefully, be the subject of future work.

Meanwhile, the search continues for other fossilized fireflies and their insect relatives.

“As the fossil record expands in the future,” the researchers write in their paper, “we anticipate further revelations that will broaden our knowledge of when, how and why bioluminescence evolved in these fascinating animals during the Mesozoic era.”

The findings have been published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.