A bird’s-eye-view of South America’s Yucatán Peninsula has revealed a massive 4,000-year-old fishery in Belize’s largest inland wetland.

The long, zigzagging network of human-made canals and ponds re-engineers the watery landscape into what some researchers describe as a massive fish trap, covering 42 square kilometers (16 square miles) in total.

Excavations on the ground have provided several radiocarbon dates for the channels, which suggest they were in use from about 2000 BCE until 200 CE.

Belize is the home of the earliest Maya settlements, but these fish traps were built at least 700 years before this civilization’s rise to prominence in the region.

“The early dates for the canals surprised us initially because we all assumed these massive constructions were built by the ancient Maya living in the nearby city centers,” says anthropologist Eleanor Harrison-Buck from the University of New Hampshire.

“However, after running numerous radiocarbon dates, it became clear they were built much earlier.”

Harrison-Buck and her colleagues working on the Belize River East Archaeology project argue these channels are part of the first large-scale prehistoric fish-trapping facility recorded in Central America.

They were probably built by Late Archaic hunter-gatherer-fisher groups, possibly as a response to long-term drought. Researchers estimate the traps once caught enough fish to feed 15,000 people for a whole year.

If true, this supports emerging evidence that suggests the Maya civilization was initially built on a feast of fishes, not necessarily a surplus of maize, as other scientists have hypothesized.

“For Mesoamerica in general, we tend to regard agricultural production as the engine of civilization, but this study tells us that it wasn’t just agriculture — it was also potential mass harvesting of aquatic species,” explains Harrison-Buck.

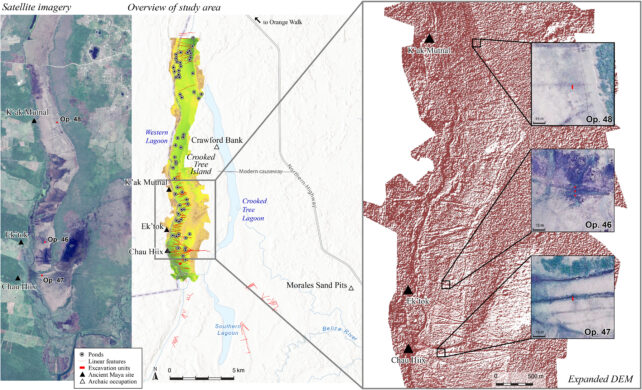

Like other researchers working on the Yucatán, Harrison-Buck’s team has recently started using aerial surveys to peer through dense vegetation or hard-to-access areas. Their focus is on the Crooked Tree Wildlife Sanctuary (CTWS), which has hosted nearly 10,000 years of continuous human occupation, along with several other locations in the Maya Lowlands, including the New River, Rio Hondo, and the Candelaria.

When lagoons in these aquatic environments dry out, the shore hosts marshy grasslands, and the subtle earthen channels built into the clay-rich soil are “barely discernible”, researchers say. Some are only 20 centimeters (8 inches) deep.

With drone footage and Google Earth satellite imagery, however, the pattern is more easily observed.

Satellite imagery includes (A) a contemporary fishery in Zambia, Africa; (B) an ancient fishery in the Bolivian Amazon; and (C) the ancient fishery in the Western Lagoon, CTWS, Belize (all images courtesy of Google Earth). (Harrison-Buck et al., Science Advances, 2024)

Previous studies have interpreted these channels as dams or water catchments for wetland agriculture. But scientists have found no pollen from maize crops, nor any agricultural fields with ditches or drains at these sites.

The waterways are reminiscent of pre-Columbian fish-traps built to the south, in the Bolivian Amazon.

Each year, during the wet season, flood cycles inundate Belize’s wetlands and lagoons, providing a good place for fish to spawn. During the dry season, however, these human-built channels divert receding waters into pools, dragging aquatic life into a confined space.

To this day, locals say these ponds still concentrate fish when flood waters subside. Because much of the region is protected from harvesting, however, most fish are left to rot as the pools slowly evaporate.

Some scientists hypothesize that an abundance of storable food is what first led hunter-gatherer societies to form settlements around important resources.

Drying, salting, and smoking an estimated million kilograms of fish each year would have easily supported a large, sedentary society living in and around the CTWS, argue Harrison-Buck and colleagues.

“Further investigations are necessary to clarify this full history,” they conclude.

The study was published in Science Advances.