Please note: This article discusses subject matter that may be upsetting to some readers.

The human body is a strange and wonderful thing. It’s also soft and squishy and vulnerable to all manner of threats, both from outside the body and within.

One extremely rare protection strategy arises in response to a very unusual and also unfortunate set of circumstances.

Every now and then, a fertilized human egg starts to develop into a fetus outside the uterus, within the mother’s abdominal cavity. Known as an abdominal pregnancy, this is very dangerous, and potentially fatal.

In a very small percentage of abdominal pregnancies, the body is able to protect itself when the fetus dies – by turning the fetus to ‘stone’.

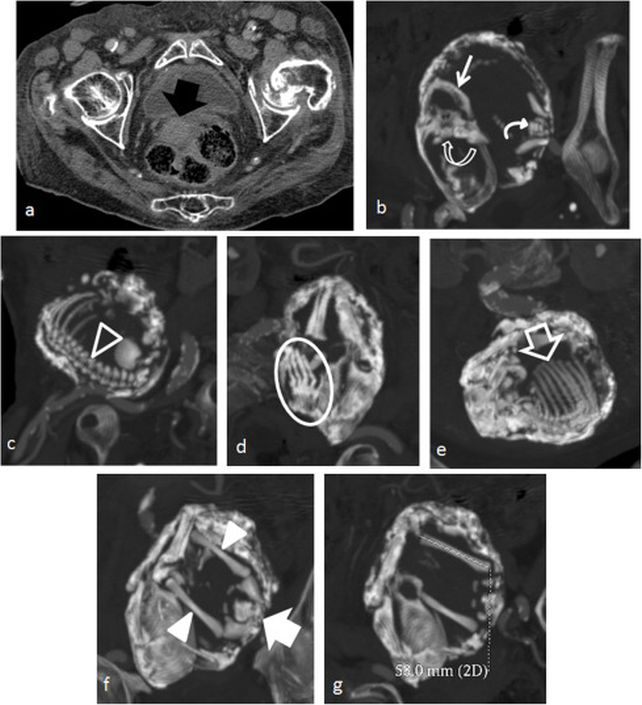

It’s not actually stone, but metal. The mother’s body permeates the fetus with the metallic mineral calcium, a major component of bones, in a process known as calcification. This safely quarantines the fetus from the mother’s own body, and thus protects her from sepsis.

The official term for such a calcified fetus is lithopedion – from the ancient Greek for ‘stone baby’ – and the phenomenon is so rare, at least in terms of it being discovered, it’s only been documented a few hundred times over the course of human history.

What makes it particularly remarkable is that, more often than not, the stone baby can remain undetected in the mother’s body for years – even decades, remaining undiscovered until well past menopause, or, in some cases, death.

The mother can even gestate and birth other babies, completely unaware of the calcium-encrusted fetal remains.

A lithopedion is thought to occur in 1.5 to 1.8 percent of abdominal pregnancies, but nowhere near that many are documented.

Abdominal pregnancy is a form of ectopic pregnancy, in which the fertilized embryo implants itself outside the uterus. The most common form of ectopic pregnancy takes place in the fallopian tube, but the ovary or the cervix are also known locations.

Roughly 2 percent of all pregnancies are ectopic; of those, an estimated 0.6 to 4 percent are abdominal. Although they’re dangerous, and the fetus usually doesn’t survive, an abdominal pregnancy can, in rare cases, deliver a live baby, typically prematurely.

A 2023 study estimates 208 million pregnancies occur worldwide every year. Based on that figure, and the lower estimates for the rates of abdominal pregnancies and lithopedions, 374 pregnancies should result in a stone baby annually.

According to a 2019 paper, fewer than 300 lithopedions have been documented across 400 years of human history.

There may be cases that go undetected. Several lithopedions have been found in ancient burial grounds, with the earliest known case dating back to 1100 BCE.

According to a 1949 review of the phenomenon, in which 128 cases were analyzed, the average age at which a mother is discovered harboring a lithopedion is 55.

In 1996, a case report detailed the discovery of a lithopedion in an 85-year-old patient who had successfully delivered four other babies prior to what her doctors described as “an incomplete abortion” at the age of 41 and went on to live for decades not knowing that parts of the fetus remained in her abdomen.

A 2000 case report detailed the phenomenon in an 80-year-old patient. A case report published in 2014 describes a lithopedion in a 77-year-old patient who believed she had never been pregnant at all. And a 2016 case report documented the case of a lithopedion in an 87-year-old deceased woman during a post-mortem autopsy.

Thanks to rising standards of gynecological and obstetric care, experts believe that the phenomenon is becoming even more rare. Abdominal pregnancies are more likely to be caught early, and treated before the fetus develops to the point of calcification.