Claims that we ought to subscribe to a low-carb, high-protein ‘paleo diet‘ are typically based on assertions our ancestors avoided complicated plant processing in favor of simpler meals consisting of meats, nuts, fruit, and raw vegetables.

Evidence is mounting that this dietary advice is based on a misconception. A new study has found Pleistocene hominins in what is today Israel had the know-how to derive a significant portion of their calories from a surprisingly wide variety of plants.

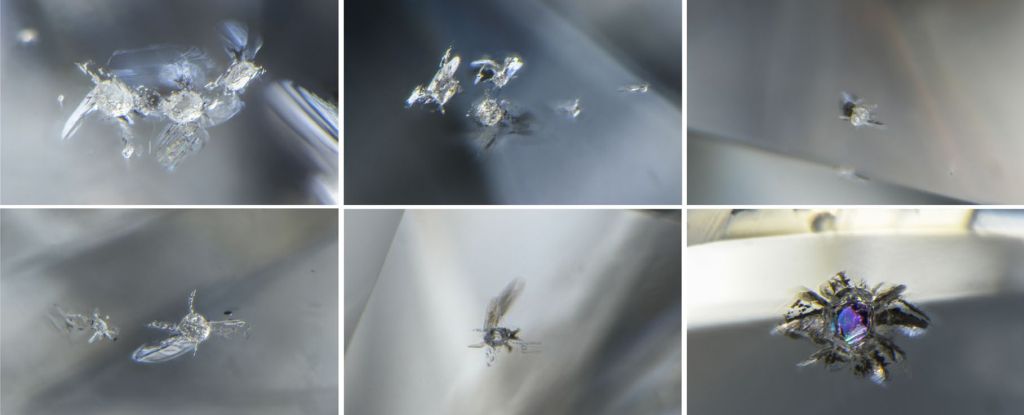

Work carried out by an international team of researchers at the Gesher Benot Ya’aqov site on the banks of the Jordan River has revealed hundreds of different starch granules and other plant matter stuck to tools encased in sediment dating back some 780,000 years.

Not only are these the oldest starch granules ever dug up by archaeologists, they’re also signs of a varied diet that goes way beyond meat: the granules were linked to oak acorns, wheat and barley grains, legumes, and edible water plants such as yellow water lilies and water chestnuts.

The tools on which these tiny remains were found, specifically hammerstones and anvils, suggest the plants had been specifically chosen and processed, implying early hominids had developed complex methods to extract nutrients and calories from diverse sources of vegetation.

“This discovery underscores the importance of plant foods in the evolution of our ancestors,” says archaeologist Hadar Ahituv, from Bar-Ilan University in Israel. “We now understand that early hominids gathered a wide variety of plants year-round, which they processed using tools made from basalt.”

“This discovery opens a new chapter in the study of early human diets and their profound connection to plant-based foods.”

Named after the Paleolithic era (around 3.3 million to 11,700 years ago), ‘paleo’ diets tend to recommend prioritizing proteins from animal sources based on the assumption that modern human physiology evolved from ancestors who were on similar diets. This meat eating has been identified as one of the driving forces behind human evolution.

It’s been assumed that most plant materials have been too tough, toxic, or impalatable to bother with. These new discoveries suggest even hundreds of thousands of years ago cultures had advanced ways of preparing vegetation as an energy source, supporting some previous studies that plants contribute greatly to the ongoing growth of the human brain.

“These results further indicate the advanced cognitive abilities of our early ancestors, including their ability to collect plants from varying distances and from a wide range of habitats and to mechanically process them using percussive tools,” write the researchers in their published paper.

This isn’t the first study to draw these kinds of conclusions. An analysis of 15,000-year-old bones and teeth found in Morocco, for example, has previously pointed towards “a substantial plant-based component” in the food of hunter-gatherers.

With the bony remnants of our kills more likely to stick around for tens to hundreds of thousands of years, it’s little wonder researchers have largely focused on the protein components of ancient diets. As technology improves, scientists are at last turning their attention to the rest of our paleolithic pantry.

“Our results further confirm the importance of plant foods in our evolutionary history and highlight the development of complex food-related behaviors,” write the researchers.

The research has been published in PNAS.