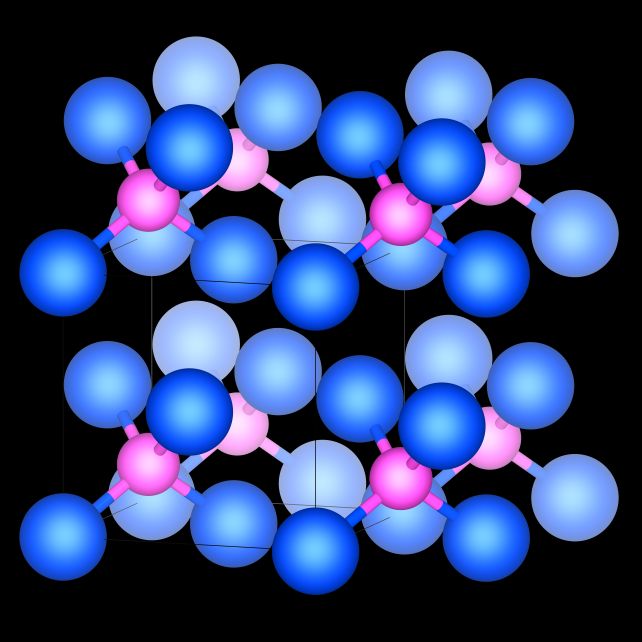

The surprise discovery that one of the lightest elements in the Universe can bind to iron under high pressure to form iron helide means we may have misunderstood the chemistry making up the profoundest depths of our planet.

That’s because it means helium could be mixed up in the core, where iron is in its most highly pressurized state in or on Earth. In fact, according to a team led by physicist Haruki Takezawa of the University of Tokyo, our planet’s dense heart of iron could harbor a large reservoir of primordial helium.

On Earth, helium comes in two stable isotopes. By far the most common is helium-4, with a nucleus containing two protons and two neutrons.

Helium-4 accounts for around 99.99986 percent of all the element on our planet. The other stable isotope, accounting for just about 0.000137 percent of Earth’s helium, is helium-3, with two protons and one neutron.

Helium-4 is primarily the product of the radioactive decay of uranium and thorium, made right here on Earth. By contrast, helium-3 is mostly primordial, formed in the moments after the Big Bang, though a portion is a by-product of the radioactive decay of hydrogen-3, or tritium.

Interestingly, when a volcano erupts, small amounts of helium-3 are detected in the gasses belched out from deep underground, leading scientists to suppose that there might be primordial helium trapped in Earth’s mantle, captured from the solar nebula of gas and dust from which our planet formed.

The work of Takezawa and his colleagues suggests an alternative source.

“I have spent many years studying the geological and chemical processes that take place deep inside the Earth. Given the intense temperatures and pressures at play, experiments to explore some aspect of this environment must replicate those extreme conditions. So, we often turn to a laser-heated diamond anvil cell to impart such pressures on samples to see the result,” says physicist Kei Hirose of the University of Tokyo, in whose lab the experiments were conducted.

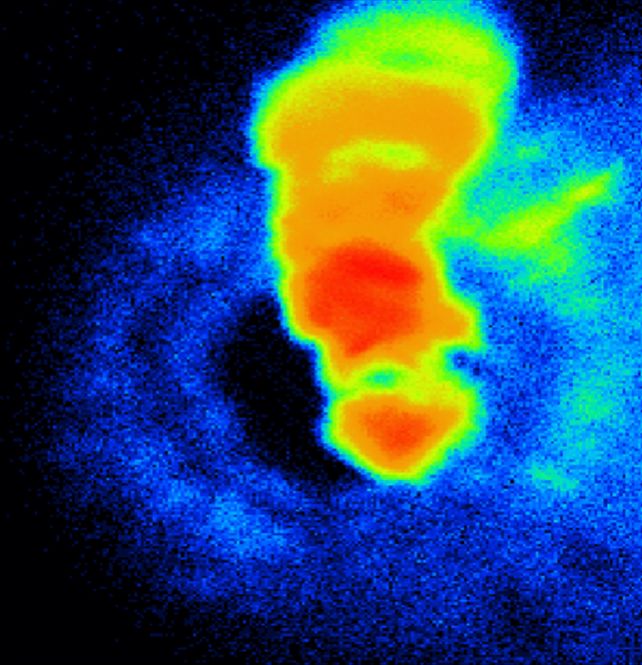

“In this case, we crushed iron and helium together under about 5-55 gigapascals of pressure and at temperatures of 1,000 kelvins to nearly 3,000 kelvins. Those pressures correspond to roughly 50,000-550,000 times atmospheric pressure and the higher temperatures used could melt iridium, the material often used in car engine spark plugs due to its high thermal resistance.”

Previous studies showed that helium binds to iron in minute, trace amounts, something in the range of just a few parts helium to a million parts iron.

In their experiments, Takezawa and his colleagues reported a ratio of helium to iron as high as 3.3 percent. That’s nearly 5,000 times higher than previously reported – a result the researchers attribute to the design of their experiment.

“Helium tends to escape at ambient conditions very easily; everyone has seen an inflatable balloon wither and sink. So, we needed a way to avoid this when taking our measurements,” Hirose explains.

“Though we carried out the material syntheses under high temperatures, the chemical-sensing measurements were done at extremely cold, or cryogenic, temperatures. This way prevented helium from escaping and allowed us to detect helium in iron.”

The finding suggests that, although helium is chemically inert under ambient conditions – that is, it doesn’t react with other elements – it can be induced to interact when conditions are pushed to more extreme levels.

In turn, this could mean that primordial helium was absorbed into Earth’s body as the planet formed, binding to iron and becoming sequestered in the core during planetary differentiation. It could also mean that primordial helium was captured in the cores of the Moon and Mars, too.

If this is the case, there may be other implications. Primordial helium in the planet’s core could be the source of the isotope in volcanic gasses, rather than a reservoir trapped in the lower mantle.

Helium isn’t the only element with a primordial isotope, either; hydrogen, the lightest element, exists in a primordial form, too. If primordial helium was present in abundance during Earth’s formation, hydrogen may have been too, contributing to Earth’s early water.

Hopefully, future work will investigate these possibilities further.

The research has been published in Physical Review Letters.