Deep under the ocean, not all ecosystems are created equal.

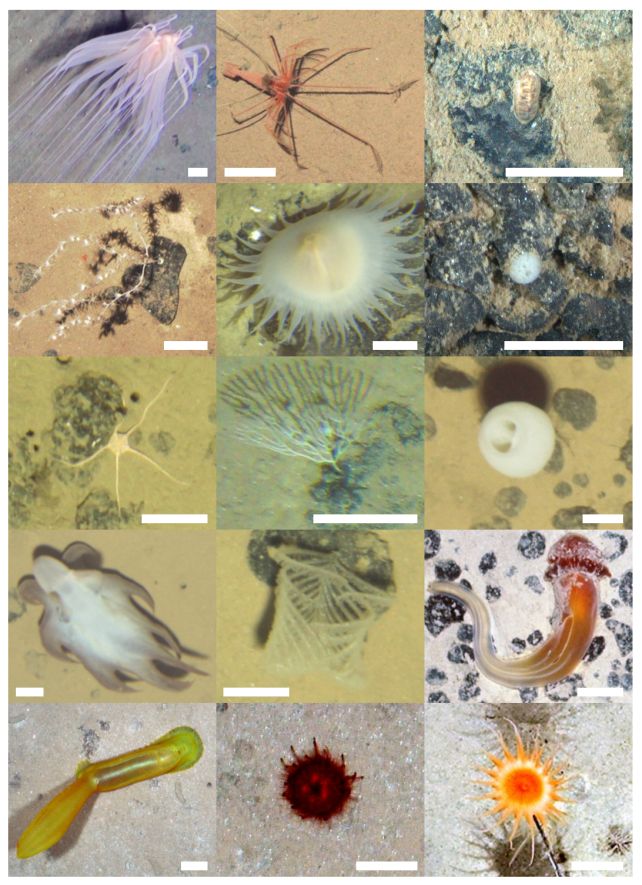

And as an international team of scientists has now discovered, the deepest depths are dominated by a specific type of organism. Below a depth of about 4,400 meters (14,436 feet), most critters that lurk in the dark have soft, soft bodies. Hard-shelled molluscs are generally only found above this limit.

Scientists assume that the reason lies in the availability of the minerals from which mussels are formed. This knowledge could help us protect biodiversity from human activity in these cold, dark, and eerie environments.

“Muddy deep-sea floors were initially considered almost ‘marine deserts’ when they were first explored many decades ago, because of the extreme living conditions there – lack of food, high pressure and extremely low temperatures,” says deep-sea ecologist Erik Simon-Lledó of the National Oceanography Center in the UK.

“But as deep science and technology advances, these ecosystems continue to reveal a great diversity of species comparable to that found in shallow-water ecosystems, only found over a much larger spatial distribution.”

The Abyssal Ocean more than covers 60 percent of the earth’s surface, but so little is known about the life that lives within it. It’s an environment anathema to humans: crushing pressures, freezing temperatures, and more eternal Darknessfar from the light of the sun.

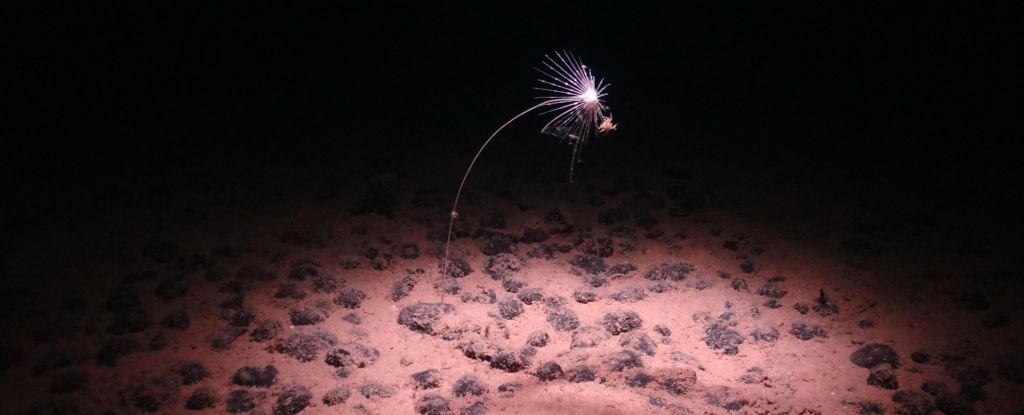

However, technology has improved to the point that we can remotely explore these darkest depths, revealing the strangely pale and soft underside of the world.

Using deep-sea robots, Simon-Lledó and his team collected a large database of images from a deep sea plain known as Clarion Clipperton ZoneIt stretches 5,000 kilometers (3,107 miles) along the bottom of the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Kiribati at depths between 3,500 and 6,000 meters.

They carefully cataloged all the animals they could find in these images that were larger than 10 millimeters. They indexed more than 50,000 abyss creatures — and they found a marked difference between the animal species found at shallower depths compared to those found in the deepest parts of the zone.

“We were surprised to find a deep province so clearly dominated by soft anemones and sea cucumbers, and a shallow abyss that suddenly had soft corals and brittle stars everywhere,” says Simon-Lledó.

Mollusks with their hard shells also did not appear below 4,400 meters, although all types of deep-sea creatures populated a transition zone between the two regions. This certain depth, the researchers found, is probably related to this carbonate compensation depth.

This forms hard shells calcium carbonate, which diffuses from the surface through the ocean. At a certain depth, however, there is not enough calcium carbonate left, leading to a lack of calcium carbonate on the sea floor. be absorbed by the hard-shelled fauna.

This suggests that there is a delicate balance in deep-sea biodiversity that could easily be disturbed by ocean acidification. climate changeand deep-sea mining, for which the Clarion-Clipperton Zone is currently being considered.

“Overall, this reflects far greater ecological heterogeneity at multiple scales than previously expected for benthic aggregations in the Northeast Pacific deep-sea floor.” write the researchers in their work.

“This overlooked heterogeneity, resulting from geochemical and climatic influences, has critical implications for future ecological and macroecological research in deep-sea communities and for the success of regional conservation strategies implemented to protect biodiversity in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone and likely other deep-sea areas targeted by deep-sea mining globally.”

The research was published in natural ecology and evolution.