The British Government recently announced that it is working with the German company BioNTech to test vaccines Cancer and other diseases.

The project aims to build on the mRNA vaccine technology that BioNTech became famous for developing and which was so successful prevent serious illness and death from COVID.

This new project aims to deliver 10,000 personalized therapies to UK patients by 2030. The studies could possibly begin as early as this fall.

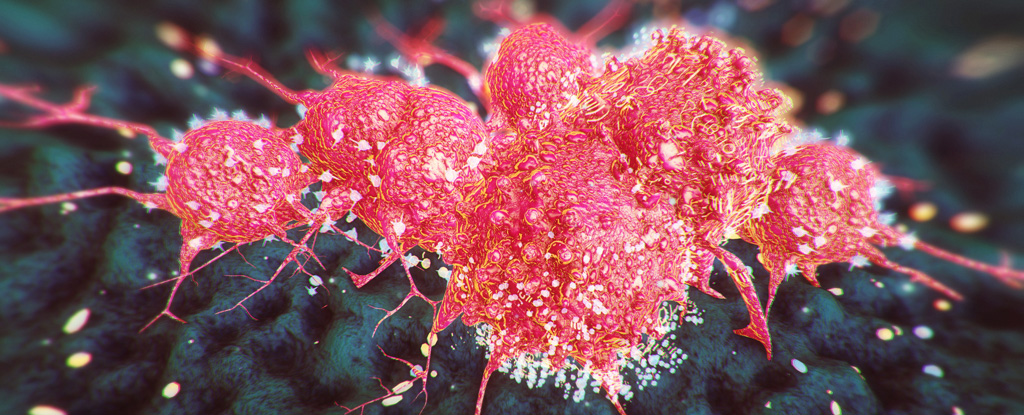

Until recently, cancer was treated with surgery (cutting out cancer cells), radiation therapy (similar to burning cancer cells), and chemotherapy (stopping cancer cells from dividing by killing them directly).

The latter is known for its strong side effects. However, in the last decade we have seen the emergence of newer treatments such as: immunotherapy. Immunotherapy usually works by blocking receptors (proteins with names like CTLA-4, PD1, or PDL1) on the surface of cancer cells.

Our immune system already knows how to fight cancer, but these proteins are used by the cancer cells to turn off the immune system.

By blocking these receptors, the immune system can recognize cancer as an enemy and kill it—like stealing the camouflage from an invader.

Although these drugs have their own side effects, they are usually much less severe than chemotherapy. And when they work, they can continue for many months or even years.

Over a decade ago, scientists noticed that they work particularly well in melanomaan aggressive form of skin cancer.

Since then we’ve seen them work in many different types of cancerfrom lung cancer to bladder cancer, from cancers with lots of PDL1 on their surface to those with lots of mutations in their DNA.

But they don’t work for every cancer and often don’t work at all. Like other cancer medicines, they can work for a while and then stop working.

Recent success with mRNA cancer vaccine

In December 2022, the pharmaceutical companies Moderna and Merck reported positive results with a personalized cancer vaccine. Patients in the ongoing study had stage 3 melanoma, meaning the cancer had spread to the lymph nodes near the cancer.

The normal course of action would be surgery to remove the tumor and surrounding lymph nodes, and then give IVs of an anti-PD1 drug (typically Merck’s Keytruda).

In this new personalized vaccine approach, scientists took samples of melanoma from patients and examined the letters in their DNA.

They took up to 34 of the most mutated bits of DNA, called neoantigens, and inserted them into a strand of mRNA — which you can think of as software inside cells between the DNA (the hard drive) and the protein (the hardware).

This mRNA was then given to patients as a personalized vaccine. It’s personalized because everyone has different neoantigens, so everyone in the study received slightly different vaccines with up to 34 different mutations encoded in just one strand of mRNA.

Just like the mRNA COVID vaccines, this mRNA made a little cancer in the patients and their immune systems responded to offer them protection.

The results of this mid-stage study showed that the addition of the personalized cancer vaccine reduced the risk of the cancer coming back (or dying from the cancer) by 44 percent compared to the standard approach (surgery followed by anti-PD1 immunotherapy).

And there were no additional side effects beyond those of existing immunotherapy.

While these results are potentially groundbreaking, we need to see results in other types of cancer in larger studies.

It is incredibly exciting that one of the larger mRNA companies, BioNTech, will be working with the UK to develop a research center in Cambridge to look at these approaches and scale them up either routinely or in trials involving 10,000 patients in the NHS.

Advances in medicine usually come in small increments, but this cancer vaccine — a new form of personalized, targeted medicine — could be a giant leap, just like the anti-PD1 or anti-PDL1 immunotherapies.

It is exciting that the UK will play a central role in this journey to making cancer not only a chronic disease we can live with, but also one we can cure.

Justin StebbingProfessor of Biomedical Sciences, Anglia Ruskin University

This article is republished by The conversation under a Creative Commons license. read this original article.