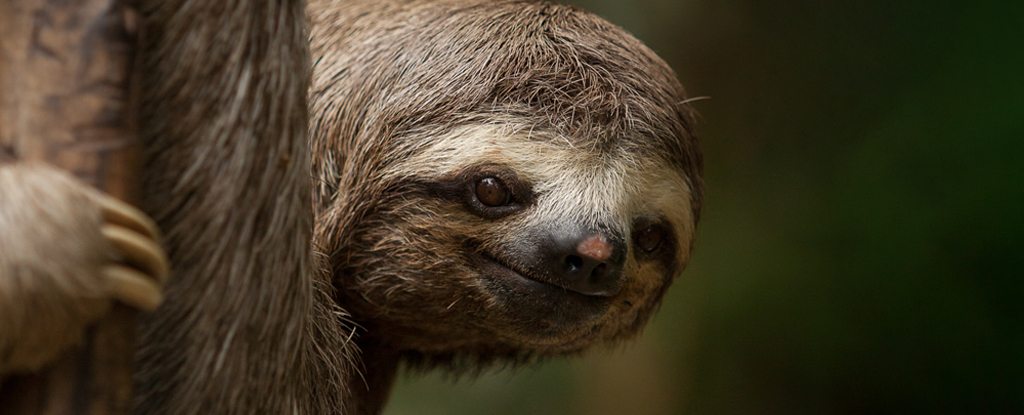

Sloths are surprisingly stronger than their adorably goofy expressions suggest, which makes sense considering they literally dangle their lives from trees by their bony fingernails.

Amazingly, although sloths use all four limbs to grasp branches, they appear to be particularly strong on their left side compared to their right. Anatomist Melody Young of the New York Institute of Technology and colleagues discovered this in the very first attempts to accurately measure the strength of a brown-throated three-toed sloth.

Very few mammals are designed for a life spent almost entirely in the canopy, especially those that live only on leaves. Honestly, while you wouldn’t be short of food, it’s difficult to extract enough nutrients from the fibrous plant matter.

Lots of mammals leaf eater (Leaf eaters) such as giraffes and moose circumvent this problem by utilizing a large digestive system. However, not all mammals can afford to reproduce in ways that help process the tough, nutrient-poor plant materials. Other mammals, like the koala, are content to squander precious energy by relaxing among the branches.

Likewise, the sloth is elongated bone claws Give them the ability to stay strong without wasting mass and energy on muscle power. According to this new study, the grip strength behind that slow dangling is exceptional for the job.

It takes two explorers to demolish a sloth hugging a third, Young told New Scientist; one explorer for each leg. And there have been some reports of sloths continue to cling to trees even in death.

Young and his colleagues built a special mount to hold this powerful grip in five brown-throated sloths (Bradypus variegatus). They found that sloths, with an average weight of 3.8 kilograms, have about twice as strong finger flexor muscles relative to their body weight as people and other primates.

The sluggish fuzzballs could easily support more than 100 percent of their body weight with just one hand or foot, with no measurable difference between front and back legs. Primates, on the other hand, are stronger in their hind legs, which also absorb about 50 to 70 percent of their weight when climbing. Sloths also distribute their weight more evenly.

But there was up to a 16 percent difference between their left and right grip strength, particularly in their hands. In contrast, primates like us tend to be stronger on the right side.

“The consistent tendency toward left-sidedness in the subjects studied was unexpected, and future work should explore the potential ecological and anatomical correlates of such a finding,” the team said writes.

Young and colleagues suspect that they actually underestimated the sloth’s grip given the limitations of their experimental setup.

“Anecdotal accounts from members of the conservation team have been described B. variegatus to grip their substrates so tightly to prevent predators from pulling them away that the skin on their backs would be more likely to peel off,” the researchers said to explain.

That’s a hell of a lot of power by any animal’s standards, let alone such a slow beast with a ridiculously low metabolism.

This research was published in the Journal of Zoology.