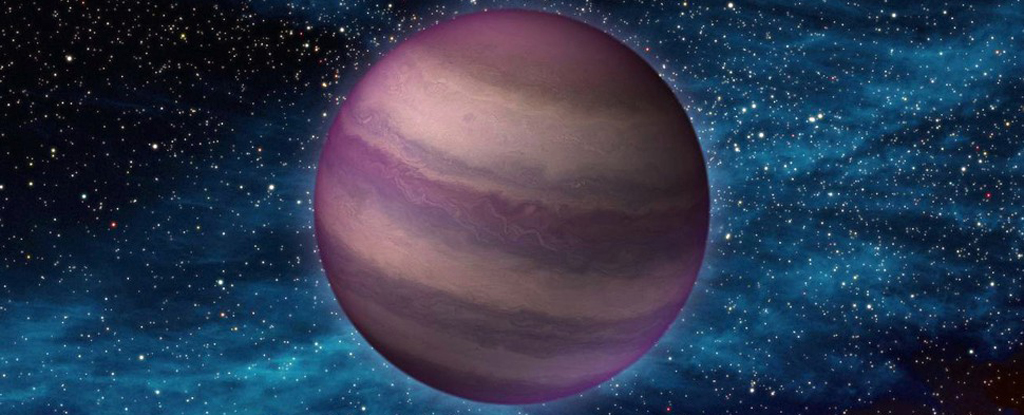

A team of astrophysicists has discovered a binary pair of extremely cool dwarfs so close together they appear like a single star.

They are notable because they take only 20.5 hours to orbit each other, meaning their year is less than one Earth day. They are also much older than similar systems.

We can’t see ultra-cool dwarf stars with the naked eye, but they are the most numerous stars in the galaxy. They are so small in mass that they only emit infrared light, and we need infrared telescopes to see them.

They’re interesting objects because theory shows stars should exist so close together, but this system is the first time astronomers have observed this extreme closeness.

A team of astronomers presented their findings at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle. Chih-Chun “Dino” Hsu, an astrophysicist at Northwestern University, led the research. The system is called LP 413-53AB.

“It’s exciting to discover such an extreme system,” said Chih-Chun “Dino” Hsu, a Northwestern astrophysicist who led the study. “In principle, we knew that these systems should exist, but so far no such systems have been identified.”

The extremes of nature play an important role in calibrating our theoretical models, and this is true for low-mass binaries. Before this discovery, astronomers were only aware of three extremely cool, short-period binaries.

The research team found the pair in archival data. They combed through data using an algorithm Hsu wrote that models stars based on their spectral data.

But in these earlier images, the stars were randomly aligned so they appeared as a single star. The odds of this happening are high for a tight binary pair like this.

But Hsu and his colleagues thought the data was odd, so they took a closer look at the star using the Keck Observatory. The observations showed that the light curve was changing so rapidly that there had to be two stars.

Eventually, they realized they had found the closest binary pair ever found.

“When we did this measurement, we could see how things changed over the course of a few minutes of observation,” said Professor Adam Burgasser from UC San Diego. Burgasser was Hsu’s advisor while Hsu was a graduate student.

“Most of the binaries we follow have round-trip times of years. So you get a measurement every few months. After a while you can put the puzzle together. With this system, we could see the spectral lines moving apart in real time. It’s amazing to see things happening in the universe on a human timescale.”

To emphasize how close the stars are to each other, Hsu compared them to our own solar system and another known system.

The couple is closer than Jupiter and one of its Galilean moons, Callisto. It is also closer than the red dwarf star TRAPPIST-1 to its nearest planet, TRAPPIST-1b.

The stars are much older than the other three similar systems known to astronomers. While these three are relatively young at up to 40 million years, LP 413-53AB, like our Sun, is several billion years old.

Their age is an indication that the stars didn’t start out so close together. Researchers believe they could have launched in an even tighter orbit.

“That’s remarkable, because when they were young, about 1 million years old, these stars would have been on top of each other.” said Burgasser.

Or the stars began as a pair in broader orbits and then converged over time.

Another possibility is that the stars started out as a triple star system. Gravitational interactions could have simultaneously ejected one star and pulled the remaining two into closer orbit.

Further observations of the unique system could help answer this.

Astronomers are interested in such stars because they might tell us something about habitable worlds. Because ultra-cool dwarves are so dark and cool, their habitable zones are narrow regions.

This is the only way they could heat the planets sufficiently to obtain liquid surface water. But in the case of LP 413-53AB, the habitable zone distance is the same as the stellar orbit, ruling out the possibility of habitable exoplanets.

“These ultra-cool dwarfs are neighbors of our sun,” Hsu said said. “To identify potentially habitable hosts, it’s helpful to start with our close neighbors. But if close binaries are common among ultra-cool dwarfs, there may be few habitable worlds.”

Now that astronomers have found a system as tight as this, they want to know if there are more. This is the only way to understand all these different scenarios.

It’s difficult to draw any conclusions at all when you only have one data point.

But astronomers don’t know if they’ve found just one because they’re so rare or because they’re so hard to spot.

“These systems are rare”, said Chris Theissen, co-author of the study and Postdoctoral Fellow of the Chancellor at UC San Diego.

“But we don’t know if they’re rare because they rarely exist or because we just can’t find them. That’s an open question. Now we have a data point to build on. This data had been sitting in the archive for a long time. Dino’s tool will allow us to search for more binaries like this.”

This article was originally published by universe today. read this original article.