A mysterious ancient graveyard that has flummoxed Finnish archaeologists for decades could be one of the largest Stone Age cemeteries in northern Europe, a new study suggests.

Located on the edge of the Arctic Circle in Tainiaro, a place of long and bitter winters, the site was first unearthed in 1959 and studied again in the late 1980s, but the findings of those excavations never saw the light of day.

Thousands of artifacts were described, and archeologists later discovered the sandy soils were tinged with ash and streaked red with ochre.

But no human remains have ever been found in the dozens of shallow pits at Tainiaro, leaving researchers to wonder what brought people to congregate on the forested shores of an almost-Arctic estuary.

Now, a new analysis of the site, led by archaeologist Aki Hakonen of the University of Oulu in Finland, strengthens the idea that the site was used as a graveyard, with up to 200 possible burial pits dug some 6,500 years ago by Stone Age communities otherwise known for their nomadic forager lifestyle.

“Even though no skeletal material has survived at Tainiaro,” Hakonen and colleagues write in their paper, “Tainiaro should, in our opinion, be considered to be a cemetery site.”

To reach that conclusion, the team pored over the old records of the site to relocate the previously excavated trenches, then excavated a few more, and compared the shape, size, and contents of the pits to other Stone Age burial sites located elsewhere in Finland.

Bones buried in the region’s acidic soils can decay in several thousand years, yet thousands of stone artifacts, scraps of pottery, and a few burnt animal bones were preserved and found scattered throughout the site.

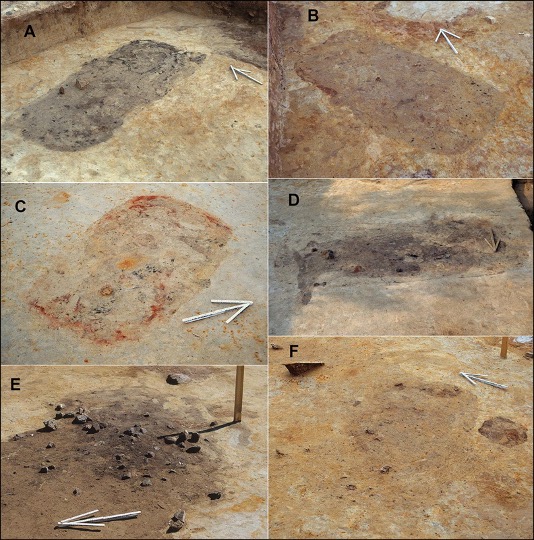

Most of the pits contained traces of ash and charcoal, though not nearly as much as the thick layers of burnt material unearthed at Stone Age hearths elsewhere. Others had occasional streaks of red ochre, but not enough to mark the hollows as ceremonial burial plots.

The shape and size of the Tainiaro pits, however, closely matched hundreds of Stone Age graves found at 14 cemeteries in northern Europe. Many of the Tainiaro pits were shallow rectangles with rounded corners, measuring between 1.5 and 2 meters long and roughly half a meter deep.

Based on their comparisons, the team interpreted 44 of an estimated 200 pits as graves, although only one-fifth of the site has so far been excavated, so much more could be revealed with further studies.

If the pits are indeed graves numbering in the hundreds, then it suggests Stone Age societies living close to the Arctic were possibly larger than previously thought. Other nearby gravesites are much smaller, Hakonen says, containing around 20 burial pits.

The team plans to use ground-penetrating radar to study the site without disturbing it. Hakonen says soil samples could also be analyzed for human DNA, fossilized hair, or animal furs and bird feathers to understand more about possible burial practices.

Just last year, researchers discovered the remains of a child whose elaborate grave, located in modern-day Finland, was layered with feathers and fur. The lucky find painted a rich picture of Stone Age communities in the region, who may have had an intimate relationship with death.

However, Tainiaro might not have been solely a sanctum for burials, given the litany of tools and scorched material found at the site, Hakonen and colleagues note. Nomads may have lit fires or worked stone tools alongside graves, living – if for a time – among the dead.

“Many questions about Tainiaro remain unanswered,” the team writes.

“For the time being, however, the notion that a large cemetery seems to have existed near the Arctic Circle should cause us to reconsider our impressions of the north and its peripheral place in world prehistory.”

The study has been published in Antiquity.