A bright infrared light emanating from two galaxies in the process of merging has just been roused from hiding.

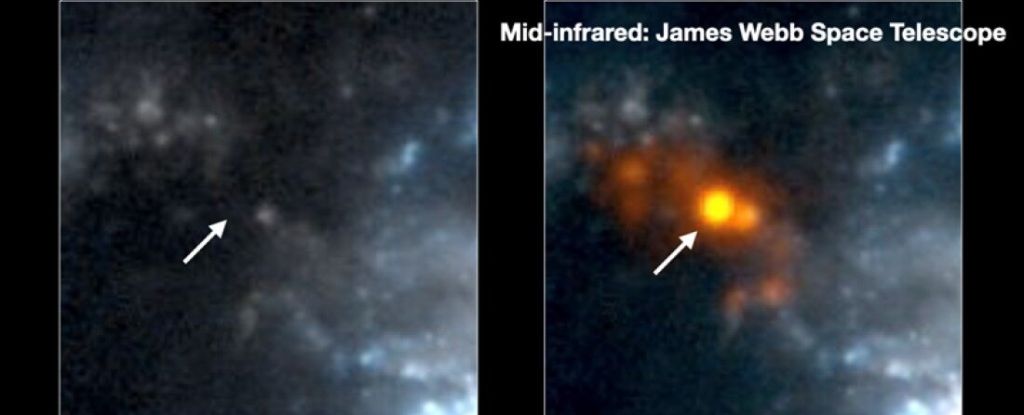

Use of JWSTastronomers have pinpointed the exact position of the light behind a thick wall of dust that obscures it at other wavelengths. Whatever is producing the light is still unknown, but narrowing down where it is helps figure out what it is and why it’s shining so much brighter than expected.

“The James Webb Space Telescope has brought us completely new views of the Universe thanks to the highest spatial resolution and sensitivity in the infrared region,” says astrophysicist Hanae Inami from the Hiroshima Astrophysical Science Center of the University of Hiroshima in Japan.

“We wanted to find the ‘engine’ that powers this merging galaxy system. We knew this source was deeply hidden by cosmic dust, so we couldn’t use visible or ultraviolet light to find it. Only in the mid-infrared, observed with the James Webb Space Telescope, do we now see this source outshining everything else in these merging galaxies.”

Although the universe is mostly empty space, mergers between galaxies are not uncommon. Massive galaxies are pulled together by the unstoppable pull of gravity, combining to form larger galaxies.

It’s not even a distant thing that only happens to other galaxies elsewhere: the Milky Way itself is a cosmic Frankenstein monster made up in part of all other galaxies it is subsumed over its billions of years of life.

Many examples of galactic mergers in various stages have been found throughout the wider universe, but it is a slow process that can take millions to billions of years.

Scientists have to take the examples we have and reconstruct the timeline around them, like a single frame from a movie, and the only other examples are single frames from similar but different movies. It’s tedious work, but it’s one of the best tools we have for understanding galaxy mergers.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; write clipboard; encrypted media; gyroscope; picture in picture; web-share” allowfullscreen>

We also know from the light emanating from these fusions that they are quite vivid. Although galaxies are primarily space, stars can collide with each other or gravitationally interact to disrupt each other’s orbits.

The clouds of star-forming gas between stars can also bump into each other, creating tremors that can trigger angry star-forming waves known as starbursts, visible as infrared light peeking out from clouds of dust.

That’s what the scientists expected when they turned on the infrared Spitzer Space Telescope to a galaxy merger called IIZw096 500 million light-years away in 2010.

Instead, they found a bright infrared light glowing in the middle of the ongoing collision. Unfortunately, Spitzer did not offer high enough resolution to find the exact location of the light source, and the mystery had to be put aside.

That’s because the longer wavelengths of infrared light don’t scatter dust like shorter wavelengths, and Spitzer did top class of its time, so no other telescope had any hope of getting closer. Then came the JWST, and Inami and her colleagues took a closer look.

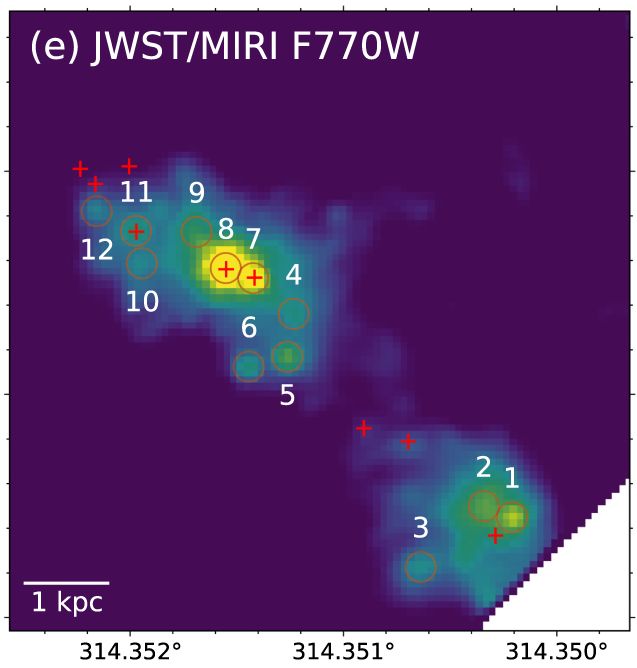

They found the source accounts for about 70 percent of the mid-infrared light emitted by the merging galaxies. Although the two galaxies together span about 65,000 light-years, the infrared source has a maximum radius of 570 light-years. This indicates that the emission source is very compact.

We know that the material around is active black hole emits a lot of light, the supermassive one at that black holes at the centers of galaxies can merge if they meet at the center of the merger. But the place of the light is peculiar; It is not in the center of either galaxy, where one would normally expect such a black hole.

“We want to know what drives this source: is it a starburst or a massive black hole?” says Inami.

“We will use infrared spectra taken with the James Webb Space Telescope to study this. It’s also unusual for the ‘engine’ to lie outside the main parts of the merging galaxies, so we’ll investigate how this powerful source ended up there.”

Researchers also identified 12 smaller mid-infrared light sources clustered around the bright “engine” in the JWST data. Some of these smaller clumps had previously been seen in Hubble near-infrared data, but five of them were new.

They’re less mysterious — the light profile matches the starburst activity — but they do indicate that something energetic is going on where the two galaxies meet.

Future analysis, the researchers hope, will lead to an identification of the source of the mysteriously bright light. In the meantime, they plan further observations to characterize the dust and gas in and around the ongoing and peculiar collision.

The research was published in The Letters of the Astrophysical Journal.