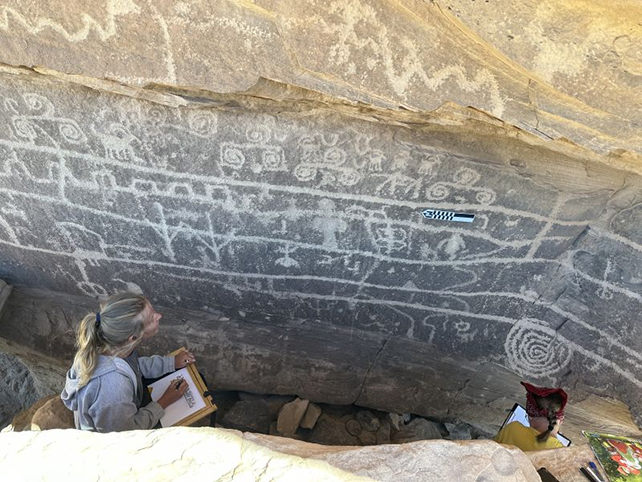

The Castle Rock Pueblo settlement complex on the Mesa Verde plateau where Colorado borders Utah is well-known for buildings within cliff-side hollows and rock art dating from thousands of years ago.

A research team from Jagiellonian University in Poland has reported back on new findings from the area, including a variety of previously undiscovered rock carvings covering a distance of some 4 kilometers (about 2.5 miles).

Considering how extensively experts have studied this part of the world in the past, the new carvings or petroglyphs are a surprising and exciting finding – and they could transform our thinking about life in the region up to around 3,000 years ago.

“I used to think that we studied this area thoroughly, conducting full-scale excavations, geophysical surveying, and digitalization,” says archaeologist Radosław Palonka from Jagiellonian University.

“Yet, I had some hints from older members of the local community that something more can be found in the higher, less accessible parts of the canyons.”

Sure enough, approximately 800 meters (2,625 feet) above the famous settlements, the researchers found a variety of lines, swirls, and other designs scratched into the walls. Some of the etchings are spirals up to a meter (almost 40 inches) in diameter, thought to be calendars that help to mark special dates and track astronomical observations.

Palonka says the findings “completely change” the perception of the area, in what’s known as the Basketmaker Era in the 3rd century CE. At the time, the Pueblo people would have lived in semi-subterranean pit houses enclosed by wooden stockades, engaging in activities such as farming and the making of mats and baskets.

“The agricultural Pueblo communities developed one of the most advanced Pre-Columbian cultures in North America,” says Palonka. “They perfected the craft of building multi-storey stone houses, resembling medieval town houses or even later blocks of flats.”

“The Pueblo people were also famous for their rock art, intricately ornamented jewelry, and ceramics bearing different motifs painted with a black pigment on white background.”

The researchers say that there may have been far more people living in the region in the 13th century than previously thought, based on the newly discovered calendars and other diagrams. It makes you wonder what historians will make of the remnants of today’s societies, thousands of years in the future.

Work is now underway to map the area in even greater detail, using LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology that should be able to get down to a resolution of 5-10 centimeters (2-3.9 inches) – and perhaps uncover even more carvings.

“We are waiting for the final results of their work and hope to spot new, previously unknown, sites, mainly from earlier periods,” says Palonka.