With depression affecting around 1 in 10 of us at some point during our lives, the need for new and improved treatments is a top priority for researchers – and it appears that spinal cord stimulation could be one route for experts to investigate.

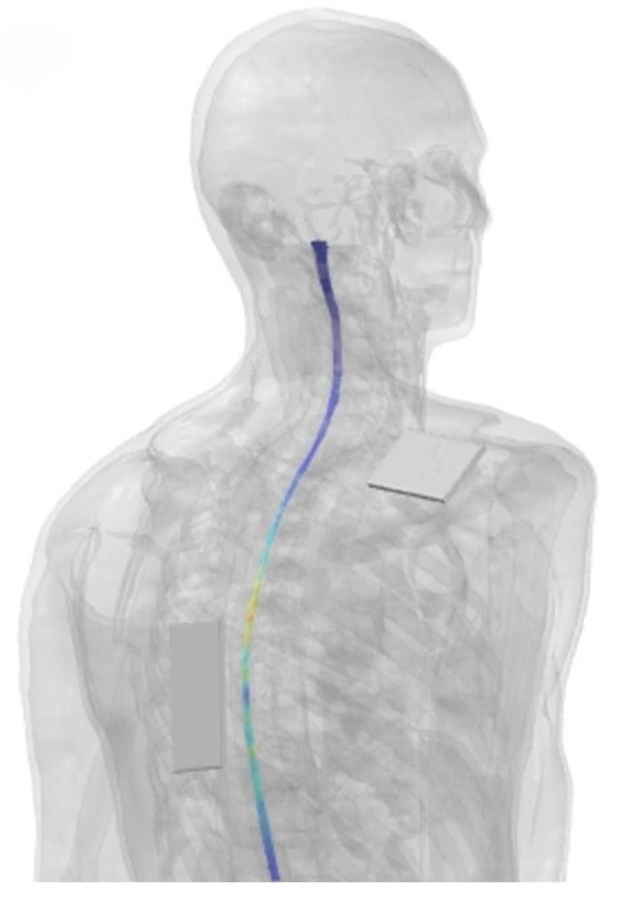

A team led by researchers at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine devised a pilot clinical trial in which a little black box was placed on the spinal cord of 20 volunteers with depression, with one electrode on the back and one on the right shoulder.

The box then delivered a specially customized, low-level electric buzz to half of the volunteers, for three sessions per week over eight weeks. This was shown to have a greater effect on depressive symptoms than the different, ‘ placebo‘ charge administered to the other half of the volunteers.

“Spinal cord stimulation is thought to help the brain modulate itself as it should by decreasing the noise or decreasing the hyperactive signaling that may be in place during a depressive syndrome,” says neuroscientist Francisco Romo-Nava, from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine.

Previous research has established that the spinal cord is constantly feeding back information to the brain about what’s going on in the body, and that this can affect emotions and mood.

The researchers hypothesize that this information pathway could get overloaded in some cases of depression. Chronic stress, for instance, might burn out the system with its constant signaling, leading to negative responses in the brain.

For the purposes of this study, transcutaneous spinal direct current stimulation (tsDCS) was used, previously shown to help regulate the electrical activity of neurons in the brain when applied to the scalp.

Here the neurons in the brain weren’t directly influenced by the signal being applied. Instead, they were shown reaching the spinal gray matter, which would then have an effect on the activity of the brain – or at least that’s the theory.

“It is not the current that reaches the brain, it is the change in the signal that then has an effect,” says Romo-Nava. “This study is not sufficient to prove all of these components of the hypothesis, but we think it’s a great start.”

This was very much an exploratory study, laying the groundwork for future research: a relatively small number of participants were involved, and the researchers didn’t look deeply at the biological mechanisms causing the change in depressive symptoms.

However, there is enough in these initial results to show it’s an approach that’s worth pursuing. Only minor side effects, including skin redness and temporary sensations of itching and burning, were noted.

“We think that the connection between the brain and the body is essential for psychiatric disorders,” says Romo-Nava.

“Many of the symptoms of mood disorders or eating disorders or anxiety disorders have to do with what one could interpret as dysregulation in this brain-body interaction.”

The research has been published in Molecular Psychiatry.