In Fayum, Egypt, where now lies a barren desert, a lush forest once stood, teeming with life.

Paradise for all creatures therein, however, it was not. The primates, hippopotamuses, elephants, and hyraxes that lived there 30 million years ago were all likely prey for one fearsome hunter: a leopard-sized apex predator with crushing jaws and razor-sharp teeth.

We know this because paleontologists have just made a startling find: a nearly complete skull from this newly discovered hypercarnivore. It belonged to a member of the extinct order of carnivores known as Hyaenodonta.

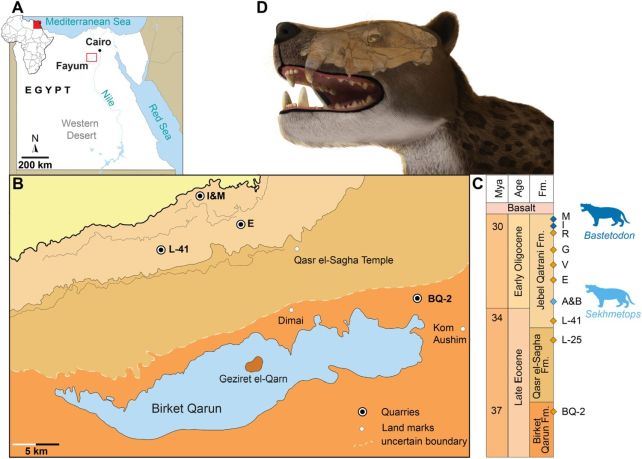

A team led by paleontologist Shorouq Al-Ashqar of Mansoura University and the American University in Egypt has given the fearsome creature the name Bastetodon syrtos, after the Egyptian lioness-headed goddess of protection, Bastet.

“For days, the team meticulously excavated layers of rock dating back around 30 million years,” Al-Ashqar recalls of the dig that yielded the fossilized skull bones.

“Just as we were about to conclude our work, a team member spotted something remarkable – a set of large teeth sticking out of the ground. His excited shout brought the team together, marking the beginning of an extraordinary discovery: a nearly complete skull of an ancient apex carnivore, a dream for any vertebrate paleontologist.”

The Fayum Depression, where the bones were found, represents an incredibly rich and important fossil assemblage for understanding a 15 million-year period in the history of the region, during the Paleogene, a crucial time in the rise of mammals.

Paleontologists have been working in the region for more than a century, uncovering the rich ecosystem that once thrived there.

“The Fayum is one of the most important fossil areas in Africa,” explains paleontologist Matt Borths of Duke University in the US. “Without it, we would know very little about the origins of African ecosystems and the evolution of African mammals like elephants, primates, and hyaenodonts.”

Although all bones are important for understanding the anatomy of extinct beasts, the skull is arguably the most important, revealing much about an animal’s survival strategies. The skull of Bastetodon reveals dentition consistent with Hyaeonodonta, allowing its confident classification, as well as insights into its lifestyle.

The animal, the researchers say, was a hypercarnivore – one whose diet, much like cats (wild ones, at any rate) and crocodiles, consists of more than 70 percent meat. It would have occupied a top predator position in its local food web.

But the discovery allowed something else – the contextualization of fossils discovered 120 years ago. These remains belonged to a group of lion-sized hyaenodonts that lived in the Fayum region millions of years ago. When they were first analyzed in 1904, they were lumped in with European hyaenodonts.

Al-Ashqar and her colleagues found that these fossils, newly grouped together under the genus Sekhmetops (for the Ancient Egyptian lioness-headed goddess of war, Sekhmet) originated in Africa in waves, and are distinct from the European hyaenodonts. Bastetodon also originated in Africa.

From there, the animals spread across the Northern hemisphere, making their way to Asia, Europe, India, and North America. However, their reign in Africa was curtailed by environmental changes that led to their eventual extinction, opening ecological niches for other predators to rise to prominence.

“The discovery of Bastetodon is a significant achievement in understanding the diversity and evolution of hyaenodonts and their global distribution,” Al-Ashqar says. “We are eager to continue our research to unravel the intricate relationships between these ancient predators and their environments over time and across continents.”

The research has been published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.