Every now and again, our planet ponies up a fossil so spectacular that almost all you can do is gape in wonder.

Sometimes those fossils are the magnificent remains that once trod Earth’s surface with thunderous feet. Sometimes, they are mere motes, particles at which you may not look twice – but contain within them the secrets of multitudes.

Such is the fossil of a sesame-seed-sized baby worm discovered encased in rock in China. Hailing from the Cambrian period some 520 million years ago, the larva represents a whole new genus and species of euarthropod called Youti yuanshi.

Such a small speck of rock might be easily overlooked, but this remarkable fossil has been almost perfectly preserved with its internal anatomy intact. And it represents a species ancestral to the arthropods that teem all over our planet today – spiders, crabs, and insects. That means it can tell us things about the evolutionary history of these animals that very few fossils can reveal.

“When I used to daydream about the one fossil I’d most like to discover, I’d always be thinking of an arthropod larva, because developmental data are just so central to understanding their evolution,” says paleontologist Martin Smith of Durham University in the UK.

“But larvae are so tiny and fragile, the chances of finding one fossilized are practically zero – or so I thought! I already knew that this simple worm-like fossil was something special, but when I saw the amazing structures preserved under its skin, my jaw just dropped – how could these intricate features have avoided decay and still be here to see half a billion years later?”

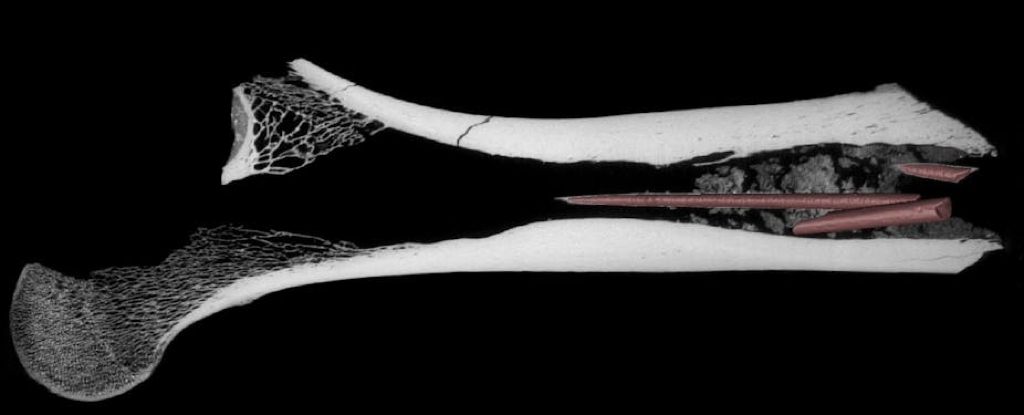

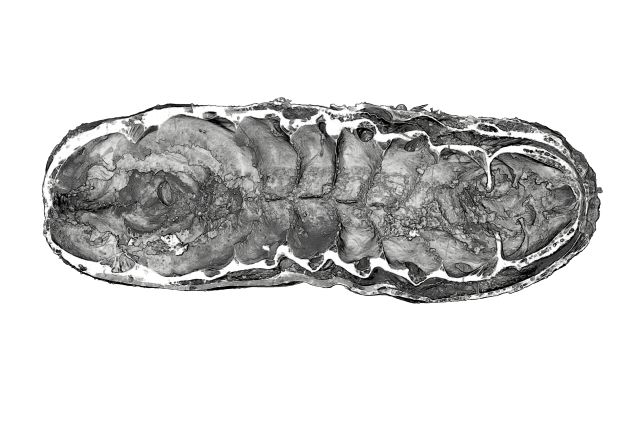

The three-dimensional fossil was found in a shale rock known to be particularly rich in fossils called the Yu’anshan Formation. It was carefully extracted using acetic acid, and then subjected to high-resolution scanning to image it throughout – and maybe catch a glimpse of whatever lurked within.

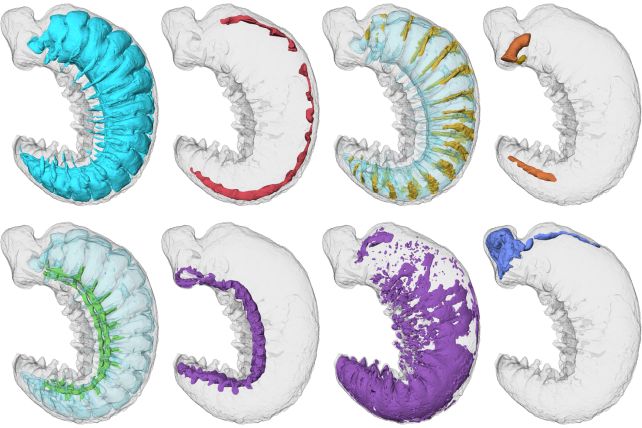

Although no bigger than just a few millimeters in size, the fossil itself is spectacularly detailed. Its exterior has a textured skin, head, and legs. And, on the inside, X-ray computed tomography revealed its intact internal anatomy. That includes the larva’s brain, digestive glands, circulatory system, and nervous system.

“It’s always interesting to see what’s inside a sample using 3D imaging,” says geologist Katherine Dobson of the University of Strathclyde in the UK, “but in this incredible tiny larva, natural fossilization has achieved almost perfect preservation.”

Because the larva is so old, and because it represents a developmental stage in an arthropod’s life cycle rarely seen in ancient fossils, scientists believe that Y. yuanshi can help us learn about the early development and evolution of this extremely successful phylum of the animal kingdom.

The worm itself seems simple compared to the complex bodies of arthropods today, but hints of the animals that would later emerge can be seen in its internal anatomy. Its protocerebrum, for instance – the worm’s brain region – foreshadows the more complex cranial anatomy that developed as arthropods evolved.

In addition, Y. yuanshi‘s circulatory and digestive anatomies can be linked to later development of arthropod features.

This early anatomy, the researchers say, highlights how brilliantly arthropods diversified, developing the ability to specialize a wide range of ecological settings and succeed across the entire globe.

Although this single Y. yuanshi fossil would be dwarfed in the palm of your hand, its discovery has big implications for our understanding of life on Earth.

The research has been published in Nature.