The earth is constantly being bombarded from space. Dustpebbles and rocks fall into our atmosphere daily and sometimes burn up spectacularly in a blazing jet across the sky.

These bolides or fireballs are typically larger pieces asteroid or comets that have broken off their mother bodies and fallen into Earth’s gravity.

However, scientists have determined that one such fireball that exploded over Canada last year is not the usual type of meteor. Based on its trajectory across the sky, a team tracked the object all the way through the solar system to a starting point on Earth Oort cloud – a vast sphere of icy objects far, far beyond Pluto’s orbit.

It is not uncommon for material to be ejected from the Oort Cloud and sent inward towards the Sun. However, this one burned and exploded in a way that said it was made of rock, not frozen ammonia, methane, and water could we expect of an Oort Cloud object.

It’s a discovery that suggests our understanding of the Oort cloud could be useful little optimize.

“This discovery supports an entirely different model of solar system formation, one that supports the idea that significant amounts of rocky material coexist with icy objects in the Oort cloud.” says the physicist Denis Vida from the University of Western Ontario in Canada.

“This result cannot be explained by the currently preferred models of solar system formation. It’s a complete game changer.”

Visitors from the Oort Cloud that we have identified so far are extremely icy. They are sometimes referred to as long-period comets, found in orbits around the sun that last Hundreds to tens of millions of years, with random inclinations and strongly elliptical.

They are thought to have been ejected between 2,000 and 100,000 astronomical units from the Sun by gravitational influences from the Oort Cloud and thrown inward on their looping orbits.

There a good number of these long-period comets have been identified, scientists have a good idea of the properties they (and their orbits) share.

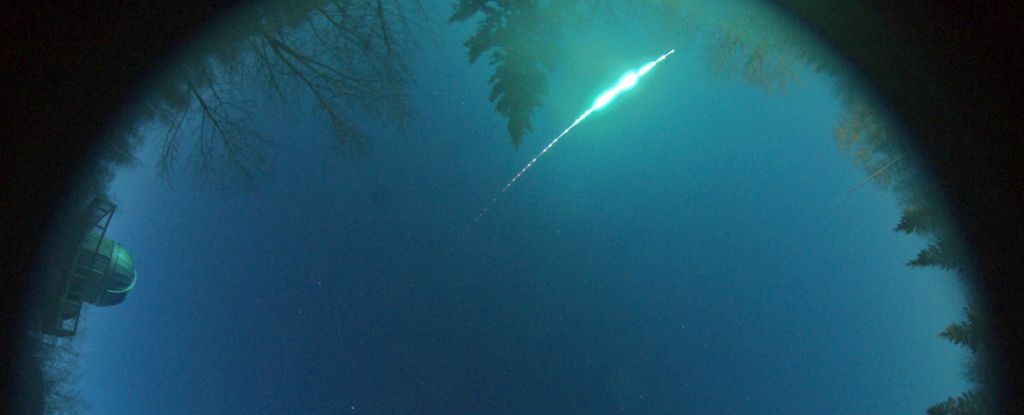

That brings us to February 22, 2021, when a ball of fire blasted across the sky about 100 kilometers (62 miles) north of Edmonton, Canada. It was observed and recorded by multiple instruments, including satellites and two cameras from the Global Fireball Observatory here on Earth.

For 2.4 seconds, these cameras tracked the meteor for 148.5 kilometers, providing scientists with detailed data on the object’s trajectory and decay. Fireballs are thought to heat up and explode when atmospheric gases penetrate tiny cracks in the rock, pressurizing it from within and making it roar.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; write clipboard; encrypted media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allow fullscreen>

The object that Vida and his team found was about 10 centimeters (4 inches) in diameter and weighed about 2 kilograms (4.4 pounds). It was thought to have fallen deeper into the atmosphere than any icy object was ever known to have. In fact, its burning and decay matched exactly that of a rocky fireball.

However, when the researchers used the data to calculate its trajectory, the results did not match the usual local meteor, but rather the orbit of a long-period comet.

“In 70 years of regular fireball observations, this is one of the strangest ever recorded. It confirms the strategy of the Global Fireball Observatory, founded five years ago, which has expanded the ‘fishing net’ to 5 million square kilometers of sky and brought together scientific experts from around the world,” says the astronomer Hadrien Devillepoix from Curtin University in Australia.

“Not only does it allow us to find and study valuable meteorites, but it’s also the only way to capture these rarer events that are essential to understanding our solar system.”

The researchers were also able to search from this one object Meteor observation and salvage project Database and published literature for possible origins of the Oort Cloud and identified two other meteors: one that fell over Czechia in 1997, named the Karlštejn Fireballon an orbit similar to Halley’s Cometand 1979 Meteor MORP 441, which also had a comet-like trajectory.

This suggests that rocky meteors could rarely land on Earth after a long journey from the Oort Cloud, which is believed to be primordial material left over from the formation of the solar system. Figuring out how and why the objects stayed rocky and ended up here is the next step.

“We want to explain how this rocky meteoroid ended up so far away because we want to understand our own origins. The better we understand the conditions under which the solar system formed, the better we understand what was necessary to kindle life.” says Vida.

“We want to paint as accurate a picture as possible of those early moments in the solar system that were so crucial to everything that happened after.”

The research was published in natural astronomy.