The ‘silent’ X chromosome within female brains may not be so silent after all.

A new study has found evidence in both mice and humans that as we age, ‘sleeping’ X chromosomes can be ‘awakened’ in brain cells critical to learning and memory.

The overlooked influence of this genetic library could be a key reason why females live longer than males and exhibit slower cognitive aging.

“In typical aging, women have a brain that looks younger, with fewer cognitive deficits compared to men,” explains neurologist Dena Dubal from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

“These results show that the silent X in females actually reawakens late in life, probably helping to slow cognitive decline.”

The X chromosome harbors about 5 percent of the human genome, and it is largely understudied in the aging brain, explain Dubal and her co-authors from UCSF, led by neurologist Margaret Gadek.

Female mammals possess two X chromosomes – one from each parent – but in each cell of the body, a random one of those chromosomes is silenced and the other is activated.

Some select genes from the X chromosome, however, can escape inactivation, and evidence suggests that as we grow older, more X chromosomes are not held down by genetic ‘gag orders’.

This means that the expression of both X chromosomes could potentially drive the different ways that male and female brains age.

To test that idea, researchers investigated brain cells in the female hippocampus, which is a brain region strongly involved in learning, memory, and emotional processing.

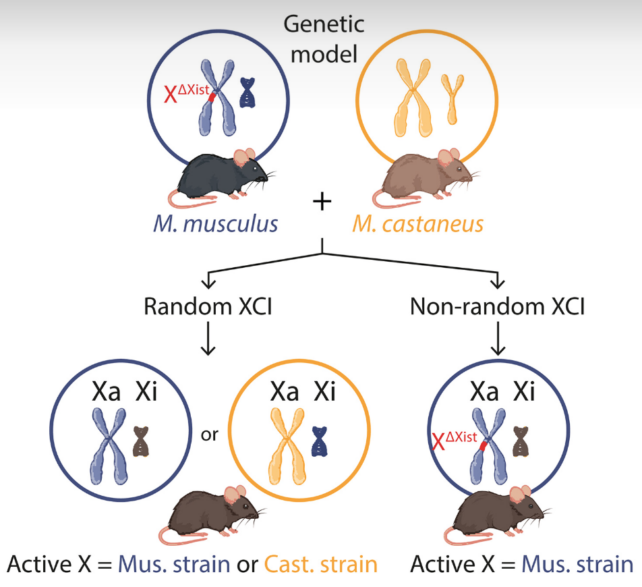

First, the team studied mice with X chromosomes from two different rodent ‘strains’, Mus musculus and M. castaneus. In their models, the X chromosome in M. musculus is missing an important gene, called Xist, which means it cannot be silenced like usual.

This means in some of their offspring the M. castaneus X chromosome is always the one getting deactivated, so if its genetic effects show up in brain cells, then it is considered an “escapee”.

Using RNA sequencing, researchers looked at the nuclei of 40,000 hippocampal cells in four young and four old female mice to figure out which X chromosome is active.

Readings that rose from the X were 91.7 percent M. musculus and 8.3 percent M. castaneus. Because the M. castaneus X chromosome was supposed to be silenced, this suggests between 3 and 7 percent of its genes somehow escaped inactivation.

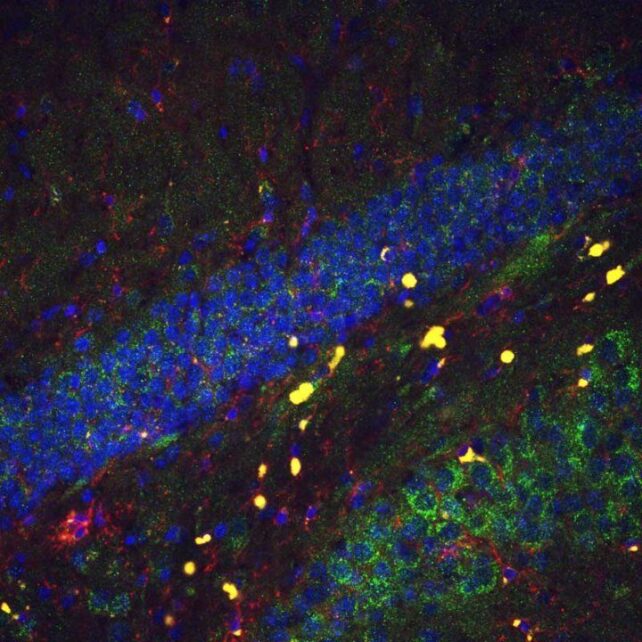

This was true of most cell types in the mouse hippocampus, and more so in older brains. The cells most likely to express genes of the inactive X include dentate gyrus neurons, which play a critical role in memory, and oligodendrocytes, which support the formation of neural connections.

To see if these findings extend to human brains, researchers at UCSF looked through previously published data on inactive X genes that change with age in at least one or more types of brain cells.

Around half of the aging-induced targets identified on the inactivated X chromosome caused human intellectual disability if mutated. This suggests that the inactivated X chromosome carries genes enriched for cognition-related factors.

One of these genes, called PLP1, particularly increases its expression with age in the neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes of the dentate gyrus. The PLP1 gene expresses a protein involved in the formation of myelin sheaths that surround neurons and allow them to send messages more efficiently.

“In parallel to mice, older women showed increased PLP1 expression in the parahippocampus, compared to older men,” the authors explain.

Increasing the expression of the PLP1 gene in male and female mice improved cognition in the aging brain, enhancing learning and memory in the animal models. This could be a possible target for future treatments of brain aging.

“The study of female-specific biology is historically underrepresented in science and medicine but is essential and expanding fervently,” the team concludes.

“What X activation broadly means for women’s brain health – or for other systems of the body – is now a critical area of investigation.”

The study was published in Science Advances.