A large communications satellite has broken up in orbit, affecting users in Europe, Central Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Australia, and adding to the growing swarm of space junk clouding our planet’s neighbourhood.

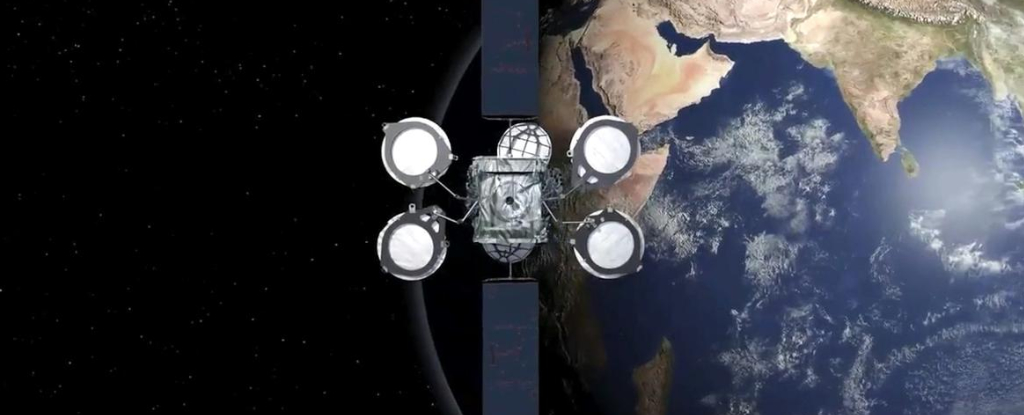

The Intelsat 33e satellite provided broadband communication from a point some 35,000 km above the Indian Ocean, in a geostationary orbit around the equator.

Initial reports on October 20 said Intelsat 33e had experienced a sudden power loss. Hours later, US Space Forces-Space confirmed the satellite appears to have broken up into at least 20 pieces.

So what happened? And is this a sign of things to come as more and more satellites head into orbit?

A space whodunnit

There are no confirmed reports about what caused the breakup of Intelsat 33e. However, it is not the first event of its kind.

In the past we’ve seen deliberate satellite destructions, accidental collisions, and loss of satellites due to increased solar activity.

What we do know is that Intelsat 33e has a history of issues while in orbit. Designed and manufactured by Boeing, the satellite was launched in August 2016.

In 2017, the satellite reached its desired orbit three months later than anticipated, due to a reported issue with its primary thruster, which controls its altitude and acceleration.

More propulsion troubles emerged when the satellite performed something called a station keeping activity, which keeps it at the right altitude. It was burning more fuel than expected, which meant its mission would end around 3.5 years early, in 2027. Intelsat lodged a US$78 million insurance claim as a result of these problems.

However, at the time of its breakup, the satellite was reportedly not insured.

Intelsat is investigating what went wrong, but we may never know exactly what caused the satellite to fragment. We do know another Intelsat satellite of the same model, a Boeing-built EpicNG 702 MP, failed in 2019.

More importantly, we can learn from the aftermath of the breakup: space junk.

30 blue whales of space junk

The amount of debris in orbit around Earth is increasing rapidly. The European Space Agency (ESA) estimates there are more than 40,000 pieces larger than 10 cm in orbit, and more than 130,000,000 smaller than 1 cm.

The total mass of human-made space objects in Earth orbit is some 13,000 tonnes. That’s about the same mass as 90 adult male blue whales. About one third of this mass is debris (4,300 tonnes), mostly in the form of leftover rocket bodies.

Tracking and identifying space debris is a challenging task. At higher altitudes, such as Intelsat 33e’s orbit around 35,000 km up, we can only see objects above a certain size.

frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen=”allowfullscreen”>

One of the most concerning things about the loss of Intelsat 33e is that the breakup likely produced debris that is too small for us to see from ground level with current facilities.

The past few months have seen a string of uncontrolled breakups of decommissioned and abandoned objects in orbit.

In June, the RESURS-P1 satellite fractured in low Earth orbit (an altitude of around 470 km), creating more than 100 trackable pieces of debris. This event also likely created many more pieces of debris too small to be tracked.

In July, another decommissioned satellite – the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) 5D-2 F8 spacecraft – broke up. In August, the upper stage of a Long March 6A (CZ-6A) rocket fragmented, creating at least 283 pieces of trackable debris, and potentially hundreds of thousands of untrackable fragments.

It is not yet known whether this most recent event will affect other objects in orbit. This is where continuous monitoring of the sky becomes vital, to understand these complex space debris environments.

Who is responsible?

When space debris is created, who is responsible for cleaning it up or monitoring it?

In principle, the country that launched the object into space has the burden of responsibility where fault can be proved. This was explored in the 1972 Convention of International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects.

In practice, there is often little accountability. The first fine over space debris was issued in 2023 by the US Federal Communications Commission.

It’s not clear whether a similar fine will be issued in the case of Intelsat 33e.

Looking ahead

As the human use of space accelerates, Earth orbit is growing increasingly crowded. To manage the hazards of orbital debris, we will need continuous monitoring and improved tracking technology alongside deliberate efforts to minimise the amount of debris.

Most satellites are much closer to Earth than Intelsat 33e. Often these low Earth orbit satellites can be safely brought down from orbit (or “de-orbited”) at the end of their missions without creating space debris, especially with a bit of forward planning.

In September, ESA’s Cluster 2 “Salsa” satellite was de-orbited with a targeted re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere, burning up safely.

Of course, the bigger the space object, the more debris it can produce. NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office calculated the International Space Station would produce more than 220 million debris fragments if it broke up in orbit, for example.

Accordingly, planning for de-orbiting of the station (ISS) at the end of its operational life in 2030 is now well underway, with the contract awarded to SpaceX.

Sara Webb, Lecturer, Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology; Christopher Fluke, Professor, Swinburne University of Technology, and Tallulah Waterson, PhD Student at the Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.