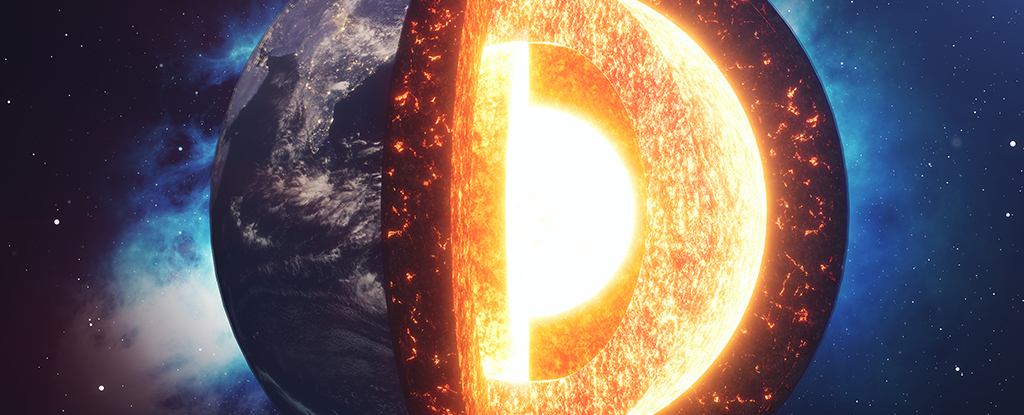

Around 3,000 kilometers (1,864 miles) beneath our feet, there’s a mysterious band of material called the D” layer, which has long fascinated scientists for its lumpiness.

Thin in patches and thick elsewhere, this layer may have formed from an ancient magma ocean thought to have covered early Earth billion years ago, new research suggests.

Chemical reactions driven by extreme pressures and temperatures at the bottom of this ancient magma ocean might have caused the unevenness we see in the D” layer today, simulations from the international team of researchers indicate.

Their simulations differ from previous models in one key way: water, which was present in Earth’s ancient magma oceans – but its effect on those oceans as they cooled and solidified has rarely been considered.

The new study posits that water could have mixed with minerals to create iron-magnesium peroxide or (Fe,Mg)O2. This peroxide attracts iron, so its presence could explain how iron-rich layers formed where the D” layer sits, just above the boundary between Earth’s molten outer core and the surrounding mantle.

“Our research suggests this hydrous magma ocean favored the formation of an iron-rich phase called iron-magnesium peroxide,” says data scientist Qingyang Hu, from the Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research (HPSTAR) in Beijing.

“According to our calculations, its affinity to iron could have led to the accumulation of iron-dominant peroxide in layers ranging from several to tens of kilometers thick.”

As the iron was dragged around, these chemical reactions were concentrated in certain areas and the D” layer formed, the team suggests in their new paper.

If their thinking is right, it would also help explain the ultra-low velocity zones (ULVZs) deep inside Earth – dense regions of material that slow seismic waves down to a crawl.

Furthermore, the researchers think these iron-rich layers would have had an insulating effect, keeping different regions down at the base of the lower mantle separate from each other.

“Our findings suggest that iron-rich peroxide, formed from the ancient water within the magma ocean, has played a crucial role in shaping the D” layer’s heterogeneous structures,” Hu says.

This magma ocean was created by a gargantuan collision with another planet some 4.5 billion years ago, scientists think.

Some leftover chunks were ejected and formed what we now call the Moon, while a heady mix of volatile elements (including carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, and sulphur) remained on our planet to help spark life.

Of course, staring back through so much time isn’t easy, and there remains a lot of scientific debate about what lies beneath the surface of Earth and how it got there. As we get better at answering those kinds of questions, we also get a better picture of what Earth was like many billions of years ago.

“This model aligns well with recent numerical modelling results, suggesting the lowermost mantle’s heterogeneity may be a long-lived feature,” says geophysicist Jie Deng, from Princeton University.

The research has been published in National Science Review.