This month marks the anniversary of a great achievement in astrophysics.

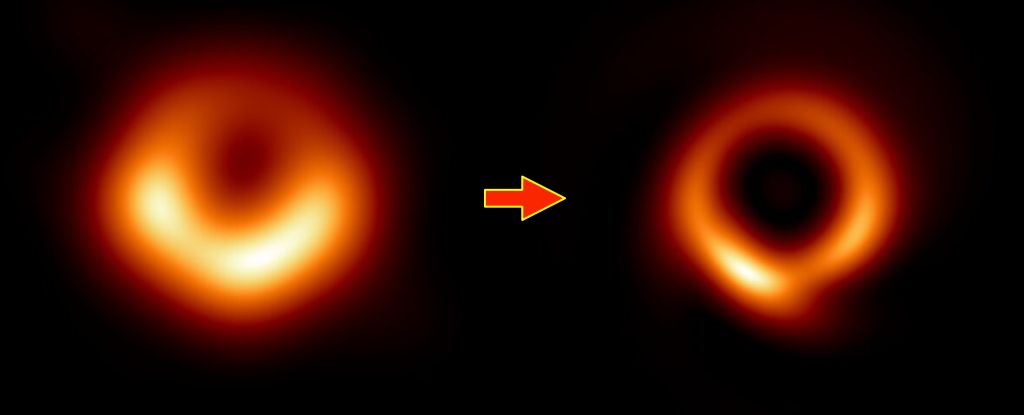

On April 10, 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration revealed the first direct image of the shadow of a black hole. Now scientists have used a new one machine learning Technique to reprocess the original data to show a new, sharper view of the bright orange material swirling around M87*.

This fresh look gives us a more detailed look at the extreme environment around a black holewhich in turn improves scientific analysis.

“With our new machine learning technique PRIMO we were able to reach the maximum resolution of the current array”, says astrophysicist Lia Medeiros of the Institute for Advanced Study and the EHT.

“Because we can’t study black holes Up close, the detail in an image plays a crucial role in our ability to understand its behavior. The width of the ring in the image is now about a factor of two smaller, which will impose a severe limitation on our theoretical models and tests of gravity.”

The galaxy with M87*, Messier 87 (or M87), is 55 million light-years distant. It was chosen as the first target for the EHT because it is relatively close and because the supermassive black hole at its center, at 6.5 billion solar masses, is large and active enough that our current technology could resolve it.

Obviously, black holes themselves cannot be seen; but an active supermassive black hole, or one actively feeding on matter, has a hot disk and torus of the material all around it glows. Even so, mapping M87* was not an easy task.

It took seven radio telescopes around the world to join forces to effectively create an Earth-sized telescope, and four days of observation to gather the data that eventually became the image we are familiar with today. Then came data processing, and that was very labor intensive.

Though groundbreaking and effective, the technique of combining the seven telescopes – known as interferometry – is not perfect. There are gaps in the data because the telescopes aren’t really one large, Earth-sized receiver — they’re spatially separated. So Medeiros and her colleagues developed a machine learning algorithm called Principal Component Interferometry Modeling (PRIMO) to fill in these gaps.

“PRIMO is a new approach to the difficult task of creating images from EHT observations,” explains the astronomer Tod Lauer of the NOIRLab of the National Science Foundation. “It offers a way to compensate for the missing information about the observed object that is needed to produce the image that would have been seen with a single gigantic Earth-sized radio telescope.”

PRIMO relies on something called dictionary learning, in which an algorithm is trained by showing it thousands of examples of a thing to learn the rules of how that thing works. Researchers trained PRIMO on over 30,000 simulated images of active black holes so it could learn how the process works and look for patterns.

According to the researchers, PRIMO then created a high-precision image of M87* with the currently maximum possible resolution. It shows the structure missing from the original image and matches – approximately – four days of data collected in 2017 5 petabytes worth – and theoretical predictions.

This new image allowed the team to take more detailed measurements of M87* than before and conduct more rigorous tests of the gravitational regime around it. In the future, the algorithm can be applied to other such images, including that of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way that became known last year.

“The picture from 2019 was just the beginning”, says Medeiros. “If a picture is worth a thousand words, the data underlying that picture has many more stories to tell. PRIMO will continue to be a crucial tool for gaining such insights.”

The research was published in The Letters of the Astrophysical Journal.