For every year of rugby played, with repeated head knocks sustained, the risk of players developing a life-altering degenerative brain disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) rises sharply, a new study finds.

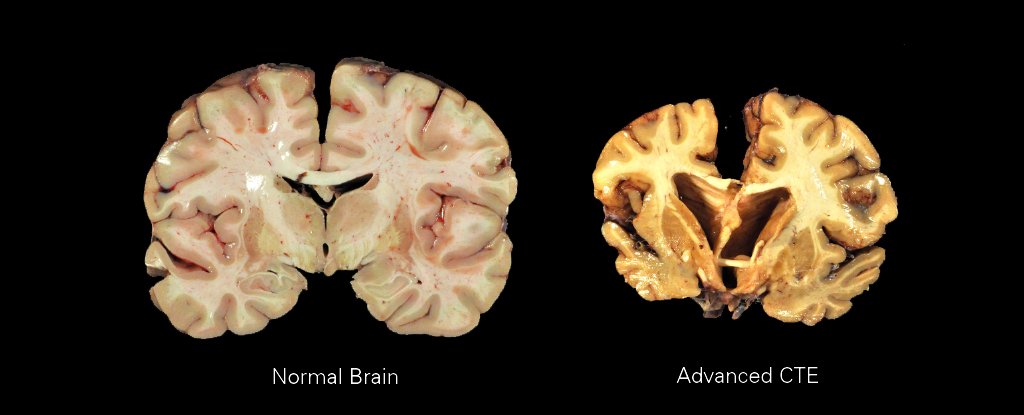

CTE is thought to be a result of repeated head injuries that slam the brain into the side of the skull, damaging its tissues.

Although a diagnosis can only be made after death, CTE most often manifests in later life as memory problems, mood changes, depression, and dementia; however people who died as young as 17 have been diagnosed with the condition.

In this new study, among 31 former rugby union players who donated their brains to research, around two-thirds (68%) of the brains examined by neuropathologists had CTE. The post-mortem diagnosis was made in both amateur and elite players.

The risk for developing CTE was linked to the length of a player’s rugby career, with each extra year of play adding 14 percent to CTE risk.

Nineteen players had reported a history of concussions, although concussions were similarly common in athletes without CTE, which suggests the number of non-concussive head knocks added up over a playing career drives brain changes.

“CTE is a preventable disease; there is an urgent need to reduce not only the number of head impacts, but the strength of those impacts, in rugby as well as the other contact sports, in order to protect and prevent CTE in these players,” says Ann McKee, study author and neuropathologist at the Boston University CTE Center.

The study, albeit small, adds another piece of evidence to the grim pattern emerging from contact sports. Amateur players as well as professional athletes, female sports stars as well as males, can develop CTE after years of grueling matches and hard-hitting training.

Much of the evidence about head knocks and CTE risk comes from NFL players: over 90 percent of ex-NFL athletes in several large post-mortem studies have been diagnosed with CTE. Studies of soccer, Australian rules football (AFL) – and now rugby players – are yielding similarly shocking results.

Rugby union has a notably high risk of concussion compared to other contact sports, yet relatively few cases of CTE have thus far been described in former rugby players, McKee and her colleagues note.

“While this current study did show some people who played amateur rugby had brain pathology, the strongest data linking contact sports to neurodegeneration still come from professional or elite players,” says Tara Spires-Jones, a neuroscientist at the University of Edinburgh who was not involved in the study.

As the evidence grows, we’ve come to understand that the biggest risk factor for CTE is repeated hits to the head, irrespective of concussion symptoms, and we now know that multiple ‘mild’ head injuries can lead to memory problems and other cognitive deficits.

In June, a study of 631 deceased football players – the largest CTE study to date – found that NFL players’ chances of developing CTE were related to both the number and strength of head impacts, and the length of players’ careers, but not the number of full-blown concussions they sustained.

These findings suggest “that we could reduce CTE risk through changes to how football players practice and play,” Dan Daneshvar, a neuroscientist at Harvard Medical School, said in June.

“If we cut both the number of head impacts and the force of those hits in practice and games, we could lower the odds that athletes develop CTE.”

The rugby study has been published in Acta Neuropathologica.