Mars – dusty, dry, and desert-clad – was once so rich in water it had not just lakes, but oceans, according to a new study.

Observations using ground-penetrating radar have revealed underground features consistent with beaches on the red planet, 4 billion years ago. It’s some of the best evidence to date that Mars was once so soggy as to host a northern sea.

The research team has named that sea Deuteronilus.

“We’re finding places on Mars that used to look like ancient beaches and ancient river deltas,” says geologist Benjamin Cardenas of The Pennsylvania State University. “We found evidence for wind, waves, no shortage of sand – a proper, vacation-style beach.”

The water history of Mars is a huge puzzle. At a glance, the planet looks as though it has never seen a drop of liquid. Its global dust storms are legendary.

It would be easy to believe that Mars has always been a ball of dry rock; yet a growing, and overwhelming, body of evidence shows that Mars didn’t just have liquid water on its surface once upon a time, but that the liquid flowed in abundance.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

So there’s no longer any question that water existed on Mars. But there are still a lot of other questions. How much water was there? How long ago did it vanish? Where did it go, and how?

“Oceans are important on planets. Oceans have a large effect on climate, they shape the surface of planets, and they are potentially habitable environments,” geophysicist Michael Manga of the University of California, Berkeley told ScienceAlert.

“Hence the ‘follow the water’ theme of Mars exploration. Most exciting to me was the chance to look beneath the surface at a place we think there could have been an ocean and to see what we think are beach deposits.”

Using data collected by the Chinese National Space Administration’s (CNSA) Zhurong Mars rover, a joint Chinese-American team led by engineer Jianhui Li and geologist Hai Liu of Guangzhou University has now given us a deeper answer to the first question, at least: enough to fill an ocean.

As it traveled along the Utopia Planitia, Zhurong used ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to take measurements of the rock up to 80 meters (260 feet) below the surface of Mars.

This technology sends radio waves into the ground; when they encounter materials of varying densities, they bounce back in different ways, allowing the generation of a three-dimensional map of structures deep below ground.

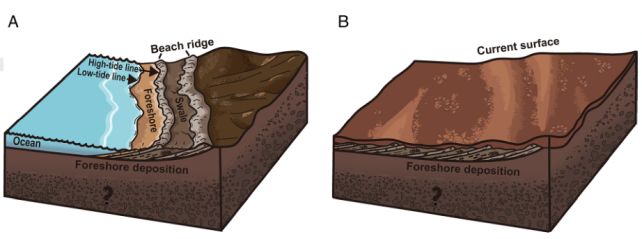

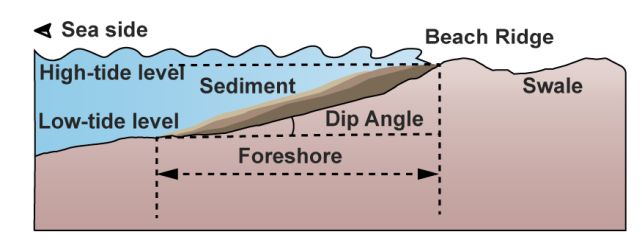

A previous study based on Zhurong data had found features that suggested a shoreline, but that interpretation was not confirmed. The GPR data revealed thick layers of material along Zhurong’s route, sloped upwards towards the supposed shoreline at an angle of 15 degrees, just like ancient buried shorelines on Earth.

“The structures don’t look like sand dunes. They don’t look like an impact crater. They don’t look like lava flows. That’s when we started thinking about oceans,” Manga says.

“The orientations of these features are parallel to what the old shoreline would have been. They have both the right orientation and the right slope to support the idea that there was an ocean for a long period of time to accumulate the sand-like beach.”

These features imply a large, liquid ocean, fed by rivers dumping sediment, as well as waves and tides. This also suggests that Mars had a water cycle for millions of years – the length of time such deposits take to form on Earth. Such deposits would not form at the edges of a lake.

“The bigger the body of water, the bigger the tides can get. And there is more space and time for wind to make bigger waves. Bigger tides and waves help shape beaches,” Manga told ScienceAlert.

Mars doesn’t have Earth’s Moon, which exerts the biggest influence on our tides here on Earth. But the Sun also exerts an influence on Earth’s ocean tides. Although ocean tides on Mars might look quite different from what we’re used to here at home, they would have existed. And surface waves are generated by wind, which Mars has aplenty.

The new discovery bolsters the case for past habitable conditions on Mars for life as we know it, and suggests a place to look for signs of ancient life on the red planet, if we can get there with the right equipment.

“Coastal environments where there is water, land, and atmosphere all together are potentially habitable environments. Knowing where and when those environments existed can help guide where we explore and how we interpret other observations like those from satellites,” Manga said.

“Shorelines are great locations to look for evidence of past life. It’s thought that the earliest life on Earth began at locations like this, near the interface of air and shallow water.”

Recent research by Manga and his colleagues suggests that much of Mars’ water may have been swallowed up into its interior, where it lurks today as vast, unreachable liquid reservoirs. This new paper could be the next piece of the puzzle: the presence of sufficient liquid water to fill those reservoirs during Mars’s fascinating, mysterious past.

The next step, though, will be to interrogate the idea of liquid oceans further, and try to model those alien waves and tides.

The team’s research has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.