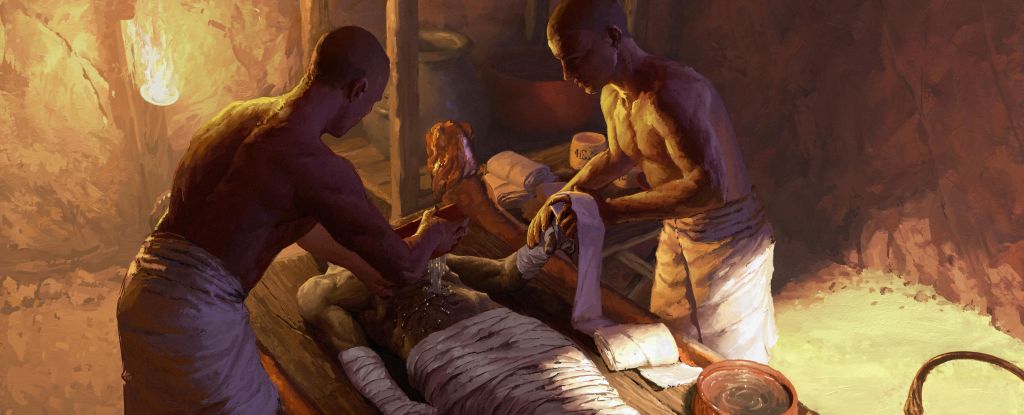

An analysis of the residues on pottery found in an ancient embalming workshop has given us new insights into the way the ancient Egyptians mummified their dead.

Even more amazing, a team of scientists managed to link different substances to the specific parts of the body they were used on.

This discovery is partly due to the residues themselves, which were studied using biomolecular techniques; but many of the vessels were intact, including not only the names of their contents but instructions for use.

“We have known the names of many of these embalming ingredients since ancient Egyptian writings were deciphered,” says archaeologist Susanne Beck of the University of Tübingen in Germany in a press statement.

“But so far we have only been able to guess which substances are behind the individual names.”

The workshop was part of a whole burial complex in Saqqara, Egypt Discovered in 2018 by a joint German-Egyptian teamfrom the 26th or Saite dynasty, between 664–525 BC.

The burial goods recovered were spectacular, including mummies, canopic jars with their organs and Ushabti figuresto serve the dead in their afterlife.

And there was the workshop, filled with ceramic jugs, measuring cups, and bowls, neatly labeled by content or use.

Led by archaeologist Maxime Rageot from the University of Tübingen, the researchers thoroughly examined 31 of these vessels Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry determine the ingredients of the embalming materials contained therein.

The detailed results are fascinating and in some cases completely unexpected.

“The substance referred to by the ancient Egyptians as antiu has long been translated as myrrh or frankincense. But we have now been able to show that it is actually a mixture of very different ingredients,” explains Rageot in the statement.

Those ingredients were cedar oil, juniper or cypress oil, and animal fat, the team found, although the mix can vary from place to place and from time to time.

The team also compared the instructions on some jars to their contents to see how each mixture was used. Instructions included “put his head on”, “bandage or embalm with it” and “make his smell pleasant”.

Eight different ships had instructions on how to treat the deceased’s head; Pistachio resin and castor oil were two ingredients unique to these vessels, often in a mixture containing other elements such as elemi resin, vegetable oil, beeswax, and tree oils.

animal fat and Burseraceae Resin was used to deal with the odor of the decomposing body, and animal fat and beeswax were used to treat the skin on the third day of treatment. Tree oils or tars could be used along with vegetable oil or animal fat to treat the bandages used to wrap the mummy, as found in eight other vessels.

Even more fascinating is what these mixtures can reveal about world trade at the time.

Pistachios, cedar oil, and bitumen all likely come from the Levant on the east coast of the Mediterranean.

However, elemi and another resin called dammar come from much further afield: elemi grows in both sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, but the tree that produces dammar only grows in Southeast Asia.

Therefore, it is possible that these two resins traveled the same trade route to Egypt, the researchers note in theirs Paper, suggesting that great effort was expended in procuring the specific ingredients for embalming. This may have played a significant role in the establishment of global trade networks.

Meanwhile, the team’s work continues on the 121 bowls and mugs recovered from the workshop.

“Thanks to all the inscriptions on the vessels, we will be able in the future to further decode the hitherto insufficiently understood vocabulary of ancient Egyptian chemistry,” says archaeologist Philipp Stockhammer from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in the release.

The excavation of the tomb complex was led by archaeologist Ramadan Hussein from the University of Tübingen, who sadly passed away last yearbefore the work could be completed.

The research was published in Nature.