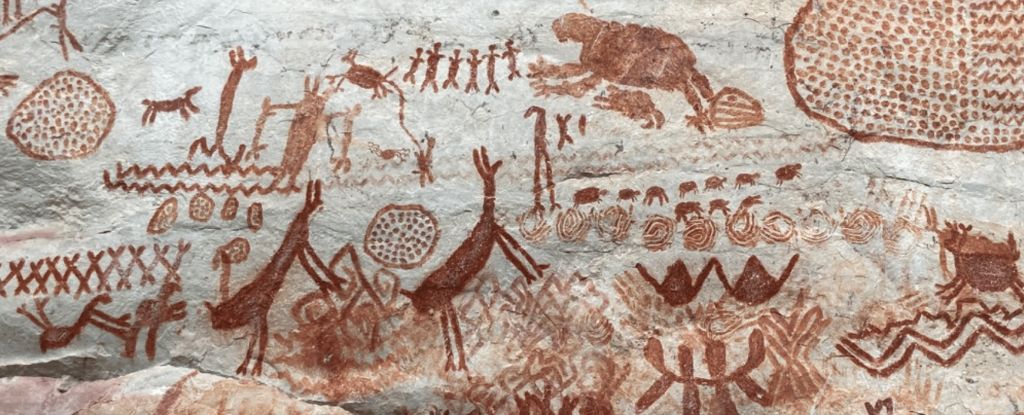

Staggeringly diverse rock art motifs in galleries across what is today Serranía De La Lindosa, Colombia, record a history of otherworldly beliefs held by the Amazon’s Indigenous peoples.

With the help of Indigenous elders and ritual specialists, Colombian and UK researchers finally documented tens of thousands of images at six of the sites after political unrest and geographical inaccessibility prevented access for most of the last 100 years.

“I have worked with rock art and Indigenous groups on every continent – and never have we been fortunate enough to have such a direct fit between Indigenous testimony and specific rock art motifs,” says University of Exeter archaeologist Jamie Hampson.

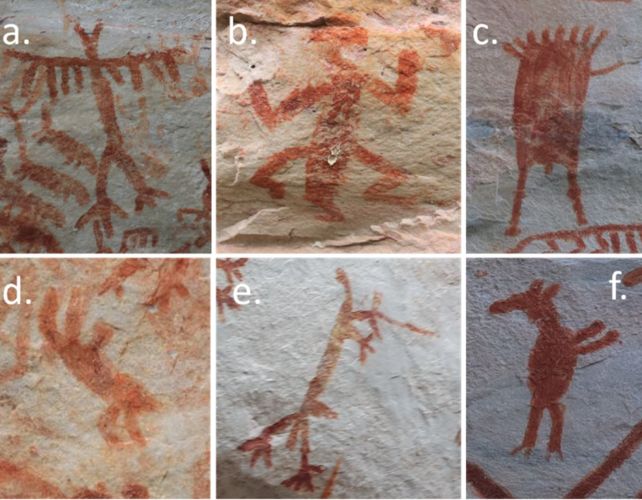

The ochre characters, some of which estimated to be more than 11,000 years old, include hundreds of human figures along with a whole ecosystem of different animals, plants, and geometric shapes.

The elders and specialists revealed the paintings aren’t just a record of what the artists observed around them at the time, but include records of ritualized negotiations with the spirit realms. The paintings include scenes of people transforming into animals, and even plant/human hybrids.

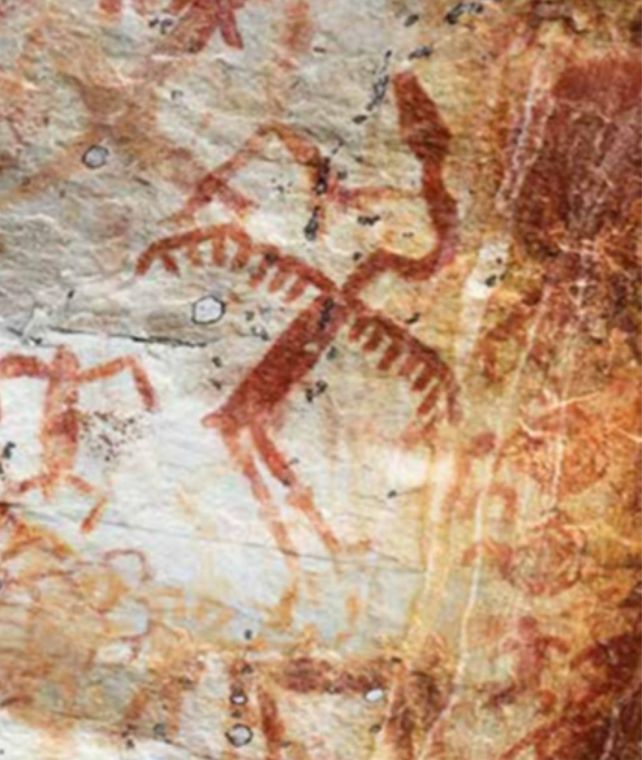

“Here are the animals that are there, they exist in that mountain range that was formerly and still is, but it is in the spiritual world…” Tukano-speaker Ismael Sierra explains of the paintings found at a site called La Fuga.

“These are men with two arms, they are giants that exist in that spiritual maloca (house)… there is an animal, a panther lion that has two heads, one head here and the other here, instead of a tail it has a head, they are from the spiritual world.”

Many Amazon cultures feature forest spirits that protect the wildlife.

“The release of game and a successful hunt requires negotiation with these spirits,” Hampson and colleagues explain in their paper.

To bridge the gap between the human and non-human world the people painted the animal they need on a rock wall with red pigment, along with other symbols to represent other requests like for fertility.

Some animals represent humans, the team explains. Jaguars are viewed as avatars for shamans, for example, as well as serving as “mediators between the three cosmic divisions of the world, between life and death, between the human world and the spirit world of the ancestors, and between nature and culture.” In at least one of the languages spoken in the area, Desana, the word yee means both jaguar and shaman.

“[The collaboration with Indigenous elders] enables us to not simply look at the art from an outsiders’ perspective and guess; we know why specific motifs were painted, and what they mean,” says Hampson. “It enables us to understand that this is a sacred, ritualistic art, created within the framework of an animistic cosmology, in sacred places in the landscape.”

Around the world, disconnection of indigenous art from its peoples puts historic records at risk of destruction. Documenting art and connecting its stories with existing cultures not only serves an anthropological purpose, it helps indigenous descendants retain their heritage.

Tukano elder Ismael fears for the future of the paintings, having been forced to leave the area due to the human conflicts.

‘Who is going to maintain [the paintings]?” asks Ismael. “Those who take care of you are spirits… No one believes it, but here are the spirits… We believe because my father was one of those [ritual specialists] who interacted with these characters here.”

This research was published in Advances in Rock Art Studies.