An ancient supervolcano in the United States may be hiding the largest deposit of lithium found anywhere in the world.

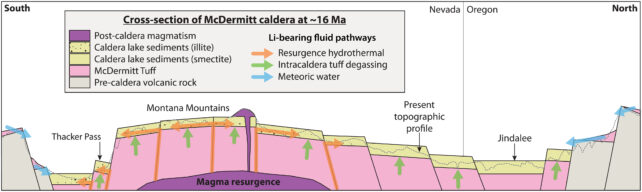

A new study hypothesizes that the McDermitt Caldera, which sits on the border between Nevada and Oregon, contains more than double the concentration of lithium seen in any other bed of clay globally, around 20 to 40 million metric tons in total.

It’s worth noting that the study was funded by a mining company, and current plans to mine the soft, silvery metal are steeped in controversy.

Many scientists, environmentalists, ranchers, and First Nations people are concerned by the US government’s recent decision to approve the Thacker Pass Lithium mine in the McDermitt Caldera, which sits on land that is sacred to several Indigenous tribes and contains precious wildlife habitats.

Today, lithium is like liquid gold for car manufacturers. It’s used to build the batteries in electric vehicles, and to meet rapidly rising demand, an estimated million metric tons of it will be needed by 2040.

Transitioning away from fossil fuels is of the utmost necessity, but this particular climate solution is hardly perfect.

In fact, the global rush to unearth more lithium could have some serious adverse impacts on nature and people. Lithium operations can destroy ecosystems, deplete groundwater, and produce masses of waste. During battery manufacturing, fossil fuels are also burned.

At the moment, the US is largely reliant on China for its lithium, so there’s been a recent push to mine more on federal lands. If all goes ahead, the Thacker Pass Lithium mine will be the second large-scale mine of its kind in the nation.

The project is owned by Lithium Nevada, LLC, a subsidiary of Lithium Americas Corporation (LAC), which funded the recent research.

According to the company’s latest review, the caldera’s southernmost rim, including Thacker Pass, contains the highest concentrations of lithium in the region.

When the ancient supervolcano erupted around 16 million years ago, hot liquid magma gushed through the ground’s cracks and fissures and enriched the clay soil with lithium, according to experts from Lithium Nevada, the University of Oregon, and the New Zealand research institute GNS Science.

Most of the caldera’s clay is called magnesium smectite, which is a known source of lithium elsewhere in the world.

But towards the southernmost rim of the caldera, researchers have found an unusual type of clay, called illite, that is especially concentrated with lithium.

This mining hotspot, the team argues, is likely the result of another resurgence of magma after the caldera’s ancient lake had dried out.

The chemical reaction that ensued from this event would have replaced lithium-smectite in lake sediment with an even richer lithium-illite claybed – but only near Thacker Pass, not throughout the caldera.

“If you believe their back-of-the-envelope estimation, this is a very, very significant deposit of lithium,’ Anouk Borst, a geologist who was not involved in the study, told Chemistry World.

“It could change the dynamics of lithium globally, in terms of price, security of supply, and geopolitics.”

But it also comes at a significant cost.

Ranchers are concerned that the lithium project will cause groundwater levels to drop to precipitous levels, and an environmental review by the US Interior Department highlighted possible dangers to native pronghorn antelope, sage grouse, and golden eagles, which are particularly sacred birds to local First Nations people.

Thacker Pass, also known as Peehee Mu’huh, is the traditional homeland of several Indigenous nations, who hunt deer here, tend to native cherry orchards, and forage for traditional medicines.

It is also the place of a bloody massacre, in which American soldiers killed 31 members of the Paiute tribe in 1865. The many caves in Thacker Pass are said to have saved the Fort McDermitt tribe from being rounded up by soldiers and sent to faraway reservations over a century ago.

Building a mine on these lands, some tribal members say, is equivalent to desecrating Pearl Harbor or Arlington National Cemetery.

“We understand that all of us must be committed to fighting climate change,” wrote the People of Red Mountain in a Statement of Opposition to the mine in 2021.

“Fighting climate change, however, cannot be used as yet another excuse to destroy native land. We cannot protect the environment by destroying it.”

The study was published in Science Advances.