Erosion isn’t a thing on the Moon like it is on Earth. With no atmosphere or tectonic plates, the lunar surface remains scarred with impact craters and covered in dust – dust that could hold clues to our lunar companion’s magnetic history.

A team of scientists has just discovered some oddly reflective dust-covered boulders in an area of the Moon already known for its peculiarities, the Reiner Gamma lunar swirl.

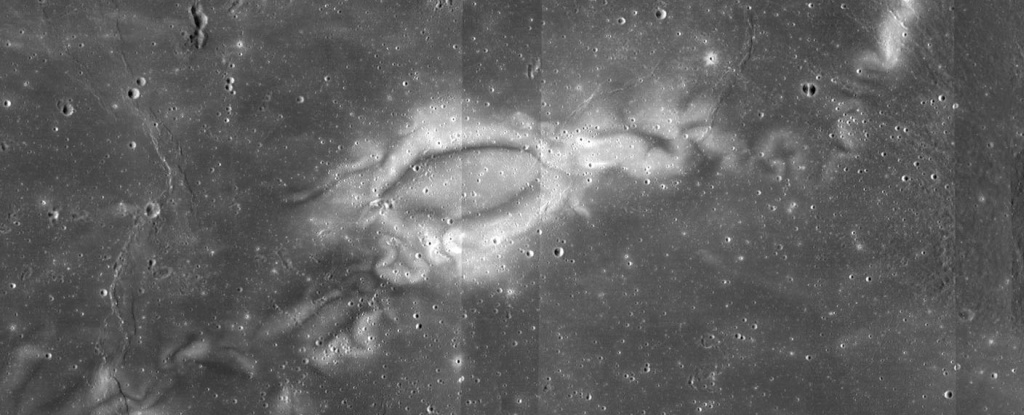

First mistaken as a crater, Reiner Gamma is actually a flat patch that casts no shadow but shines brightly against the darkness of a vast lunar plain called Oceanus Procellarum.

Lunar swirls like Reiner Gamma are thought to be produced by, or at least associated with, pockets of magnetized rock that deflect solar wind particles. The thinking is that the magnetized material is shielded from the solar wind, which darkens surrounding areas through chemical reactions, creating swirls that are so prominent they can be seen from Earth.

But other theories suggest the swirls may have formed because of interactions between magnetic anomalies in the lunar crust, and electrically charged fine dust particles lofted by micrometeorite impacts. It’s also possible the swirls and magnetic fields both formed from plumes of material ejected by comet impacts.

To better understand those interactions, Ottaviano Rüsch, a planetary scientist at the University of Münster in Germany, and colleagues combed through around one million images of fractured rocks snapped by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which is circling the Moon.

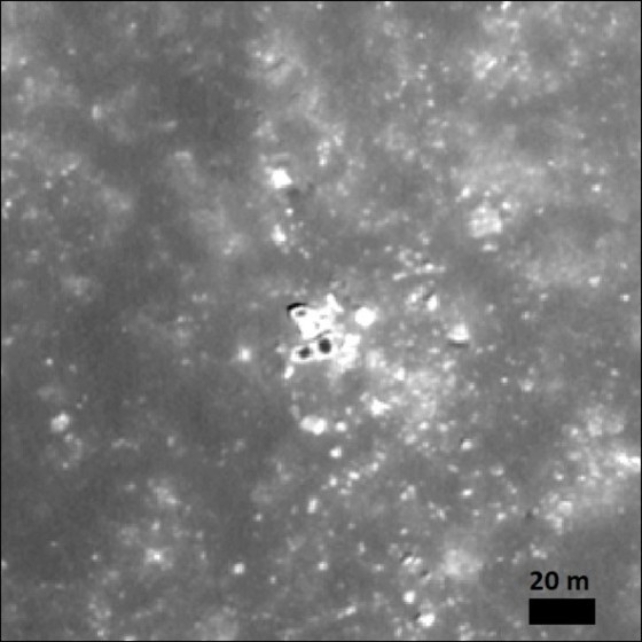

In the Reiner K crater near the Reiner Gamma swirl, they spotted one rock that was reflecting light in a way quite unlike any dust-covered boulders they had seen.

“We recognized a boulder with distinctive dark areas on just one image,” explains Rüsch, who led the initial 2023 survey and latest study. “This rock was very different from all the others, as it scatters less light back towards the sun than other rocks.”

Its peculiar properties prompted the researchers to look for more dusty boulders like it, using artificial intelligence to sort out the odd-looking ones based on size and reflectance. The algorithm identified around 130,000 possibilities, half of which the researchers scrutinized.

The less reflective rocks were localized near the Reiner Gamma magnetic anomaly, but not all rocks in the Reiner K crater exhibited odd reflectance.

So while the rocks may have formed from the crater impact, the researchers suspect their strange reflective properties are more likely due to a thin layer of dust accumulating on some, but not all, of the boulders. This dust probably has a unique density, size, or structure, although the properties are still unclear.

The team says their next step is to use their findings to investigate processes that may explain how lunar swirls form, such as the lifting of dust due to electrostatic forces or the interaction of the solar wind with patches of magnetism in the lunar surface.

Meanwhile, NASA and researchers at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory are preparing to send a lunar lander to visit Reiner Gamma, to investigate its magnetic anomalies on the ground. The lander is due to launch in 2024.

The study has been published in the Journal of Geophysical Research – Planets.