Anorexia nervosa is a serious mental health condition, characterized by restricted eating, fear of weight gain, and insidious body-image disturbances. Patients face increased risk of severe anxiety, depression, and malnutrition.

According to a new study, anorexia may arise at least partly due to changes in neurotransmitter function within a patient’s brain.

While the origins and mechanics of anorexia are still not fully understood, this finding may offer valuable insight into how this condition works – and hopefully help reveal better techniques for treating it.

Earlier research has linked anorexia with dramatic changes in brain structure, and in mouse studies with a deficiency of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine in the striatum, which plays a key role in the brain’s motor and reward systems.

The new study highlights a type of protein receptor in the central nervous system called a mu-opioid receptor, or MOR. These receptors are part of a complex opioid system in the brain, the researchers note, supporting control of eating behavior both for sustenance and pleasure.

Anorexia is significantly associated with higher MOR availability in brain regions involved with reward processing, the study’s authors report.

“Opioid neurotransmission regulates appetite and pleasure in the brain. In patients with anorexia nervosa, the brain’s opioidergic tone was elevated in comparison with healthy control subjects,” says co-author Pirjo Nuutila, physiologist at the University of Turku in Finland.

“Previously we have shown that in obese patients the activity of the tone of this system is lowered. It is likely that the actions of these molecules regulate both the loss and increase in appetite.”

The study featured 13 patients with anorexia nervosa, all female, ranging from 18 to 32 years old. Each had a body mass index (BMI) of less than 17.5 kilograms per square meter and was diagnosed less than two years prior.

The researchers compared these patients with 13 healthy controls, also all females between 18 and 32 years old, but with a BMI of 20 to 25 kg/m2 and no eating disorders or history of obesity.

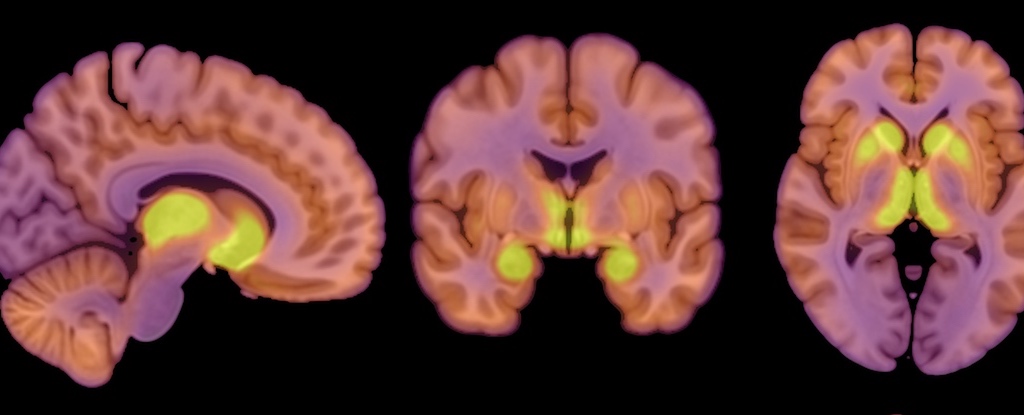

Nuutila and her colleagues measured MOR availability using positron emission tomography (PET) scans, but also used PET to measure the subjects’ brain glucose uptake.

The human brain needs a lot of fuel, accounting for roughly 20 percent of a person’s total energy consumption, the researchers note. They wanted to find out how the brain’s energy balance is affected by the reduced energy intake anorexia patients experience.

The brain seems to take priority, their findings suggest, still receiving its standard rations even when there isn’t enough glucose for the rest of the body.

“The brains of patients with anorexia nervosa used a similar amount of glucose as the brains of the healthy control subjects,” says co-author Lauri Nummenmaa, professor of cognitive neuroscience at the University of Turku.

“Although being underweight burdens physiology in many ways, the brain tries to protect itself and maintain its ability to function for as long as possible.”

Since anorexia was associated with elevated MOR availability, yet brain glucose uptake remained unchanged, the body’s endogenous opioid system might be one of the key components underpinning anorexia, the researchers say.

The effect of this up-regulated MOR availability in anorexia is a “mirror image” of the down-regulated MOR system seen in obesity, the authors note. Previous studies have also shown up-regulation of MORs following weight loss.

The study has some limitations, as the researchers acknowledge. For one, study subjects were all female because anorexia is more predominant in females, they explain, but that means these results may not apply to males.

The sample size is small, too, with only 13 anorexia patients and 13 controls.

The researchers opted against a questionnaire about eating behaviors, since anorexia patients could be especially sensitive to such questions. As a result, however, the study couldn’t link changes in MOR availability and brain glucose uptake with patients’ eating habits.

It also remains unclear whether the observed change in patients’ opioid systems is a cause or result of anorexia, the researchers point out.

More research is needed, but this study nonetheless highlights a significant and compelling link, and hints at anorexia mechanics that make sense given what else we know about the brain’s role in governing both diet and mood.

“The brain regulates appetite and feeding, and changes in brain function are associated with both obesity and low body weight,” Nummenmaa says.

“Since changes in opioid activity in the brain are also connected to anxiety and depression, our findings may explain the emotional symptoms and mood changes associated with anorexia nervosa.”

The study was published in Molecular Psychiatry.