A method for slowing disease progress in Alzheimer’s patients may also delay onset in people predisposed to the disease who are yet to show symptoms.

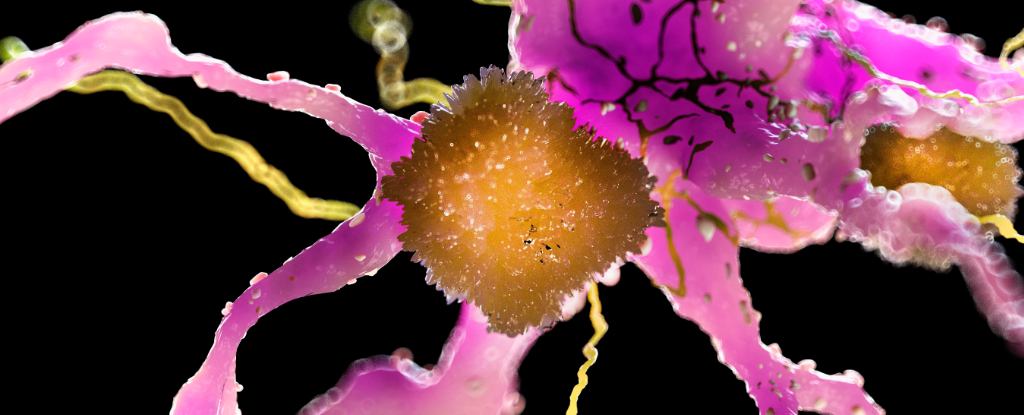

The just-published results from a clinical trial on an experimental drug targeting amyloid plaque buildup suggest the treatment can indeed put the brakes on cognitive decline, if it’s taken early enough.

“I am highly optimistic now, as this could be the first clinical evidence of what will become preventions for people at risk for Alzheimer’s disease,” says Washington University neurologist and senior author, Randall J. Bateman.

“One day soon, we may be delaying the onset of Alzheimer’s disease for millions.”

The trial involved 73 volunteers with Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s, which is caused by genes that ramp up the production of the amyloid protein. Though the mutations are responsible for just 1 percent of all Alzheimer’s cases, they make the development of the condition by their 50s a near certainty.

In 2012, research was initiated into the potential of a therapy based on a combination of two antibodies in slowing the progress of the disease in individuals with no or with minor cognitive decline.

Though the phase 3 clinical trial failed to impact the symptoms of the two groups, one of the drugs – gantenerumab – seemed to cause dramatic improvements in the pathology itself.

Encouraged by the clinical signs of a drop in protein markers, researchers continued investigations into whether higher doses of the treatment might make a difference.

Participants with higher-risk mutations were invited to remain with the trial and receive the drug regardless of whether they were initially in the control group that had only been given the placebo previously.

The extension was itself cut short due to the failure of the clinical trials to meet established goals, but an analysis of gantenerumab’s impact established it still had potential.

Among those who had taken the drug for both the trial period and its extension had their risk of developing symptoms cut in half. The effect might even be more dramatic – the risk of the non-symptomatic group declining in mental health only increases with age.

With time, comparisons between those who had taken the drug since 2012 and those who had only taken it for a couple of years, could yet show an even greater chance of delay.

“Everyone in this study was destined to develop Alzheimer’s disease and some of them haven’t yet,” says Bateman.

“What we do know is that it’s possible at least to delay the onset of the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and give people more years of healthy life.”

Using antibodies in this fashion isn’t without risk. Gantenerumab and similar treatments have been linked to tiny bleeds and swellings in the brain, which in rare circumstances can become fatal. Microbleeds are also known to increase as Alzheimer’s progresses.

Other next-generation anti-amyloid treatments have been approved in the US for the treatment of individuals who have Alzheimer’s symptoms, potentially adding years of improved cognition to their lives.

Time will tell whether those anticipating neurodegeneration in the coming decades may also be given a reprieve. But signs that researchers are on the right track are looking increasingly positive.

This research was published in The Lancet Neurology.