It took a birds’ eye view for archaeologists to realize prehistoric communities of Central and Eastern Europe were still thriving during the Late Bronze Age.

That’s a big deal, because these Carpathian Basin societies were thought to be in a state of fragmentation and collapse at that time.

In fact, most of the civilizations that encircled the Mediterranean and its adjacent seas were headed towards disaster, known as the Late Bronze Age collapse.

An international team, led by archaeologist Barry Molloy from University College Dublin, Ireland, started their investigation on the ground doing surveys, excavation and geophysical prospection.

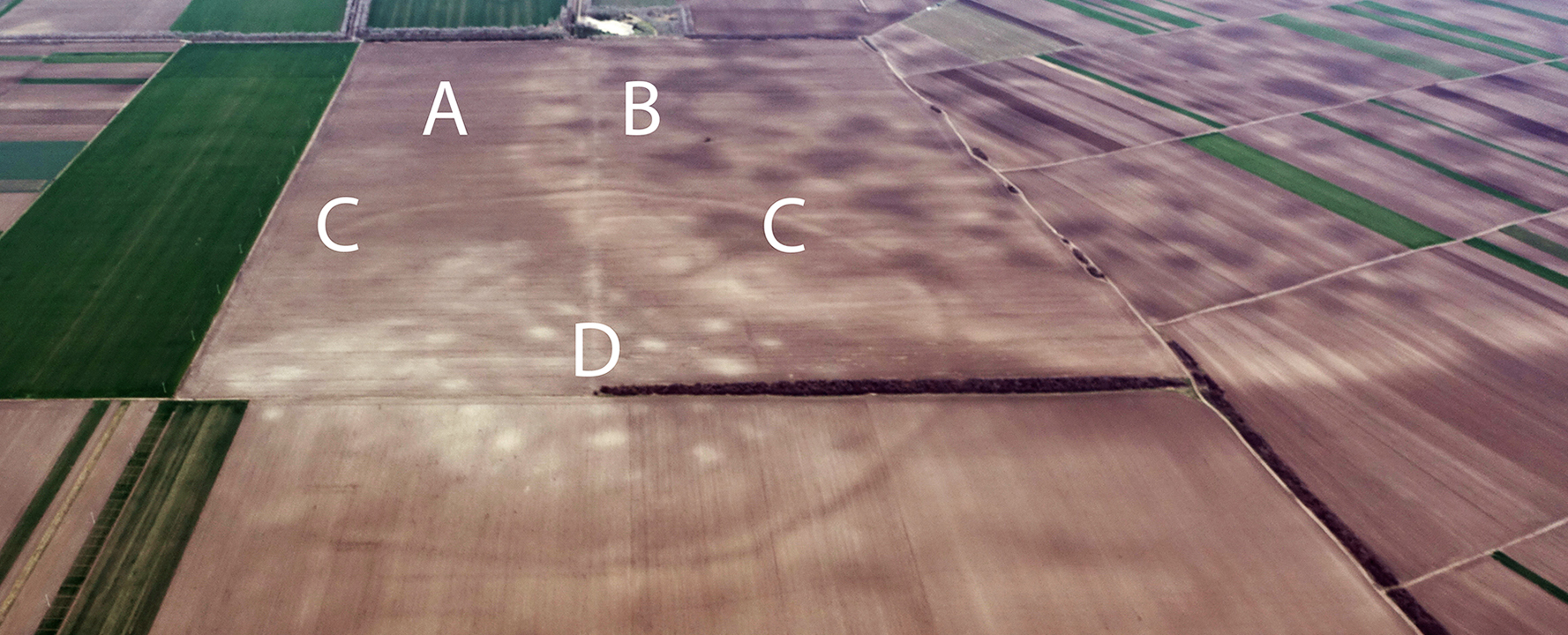

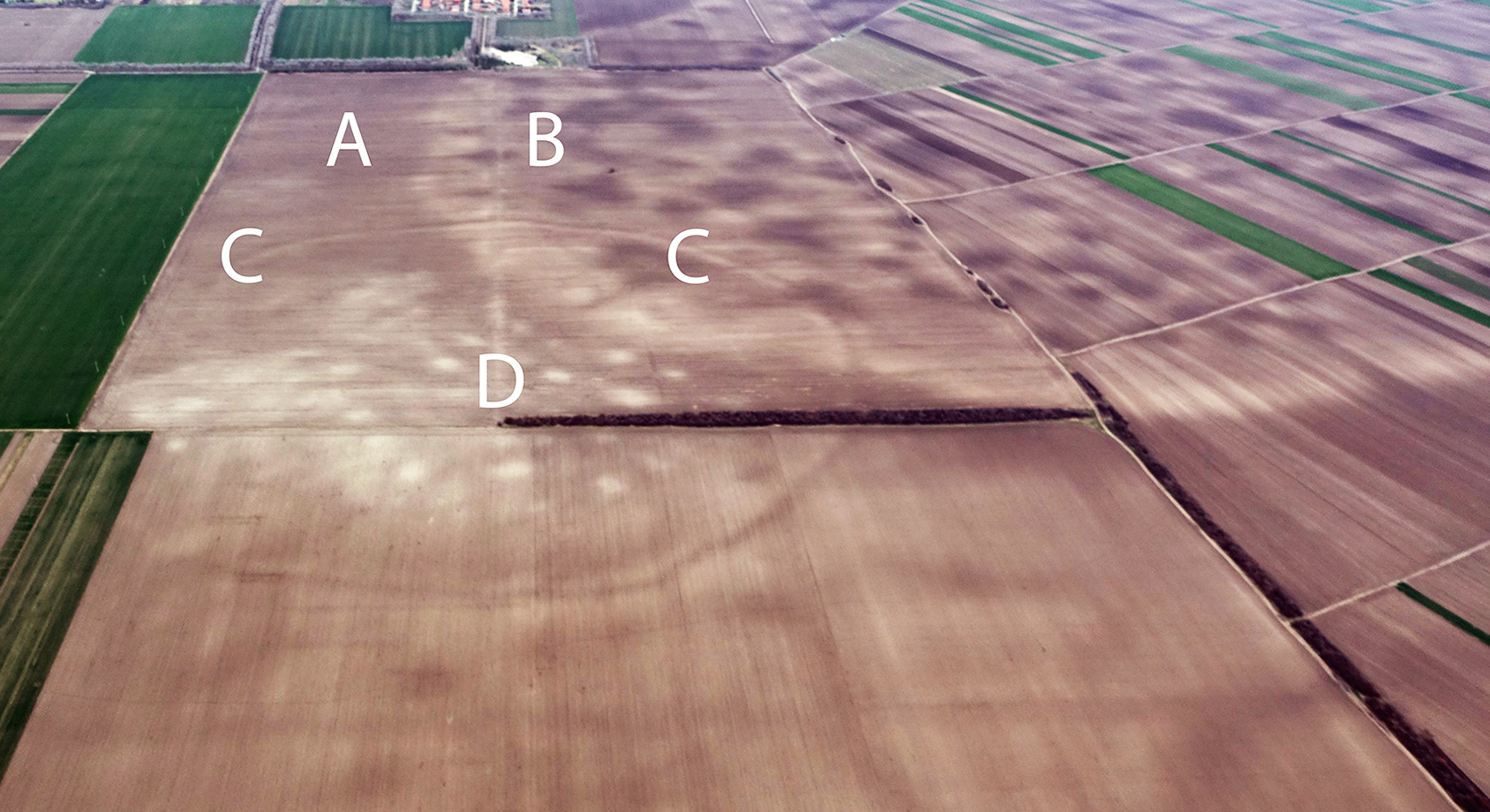

But it wasn’t until they stitched together aerial photographs and satellite images of the south Carpathian Basin in Central Europe – known for its cache of prehistoric forts – that the full picture was revealed.

“Some of the largest sites, we call these mega-forts, have been known for a few years now, such as Gradište Iđoš, Csanádpalota, Sântana or the mind-blowing Corneşti Iarcuri,” Molloy said.

Corneşti Iarcuri – the largest Bronze Age fortress in Europe – is enclosed by 33km (20.5 miles) of ditches and ramparts, far larger than the citadels and fortifications of other Bronze Age civilizations like the Hittites, Mycenaeans, or Egyptians.

In the 16th century BCE, these large central nodes were abandoned, which has led archaeologists to assume the society totally collapsed, foreshadowing the fate of many civilizations in the Late Bronze Age.

However, Molloy and his team no longer think this was entirely the case for the Carpathian basin societies – at least, not until the 13th century BCE.

“These massive sites did not stand alone, they were part of a dense network of closely related and codependent communities. At their peak, the people living within this lower Pannonian network of sites must have numbered into the tens of thousands.”

Although these enormous centers of power were in decline, in 1600-1450 BCE people in the south Pannonian Plain were forming their own polities, or small political states, into a network of monumental settlements and smaller sites, most within about 5 km of each other.

Molloy and his team discovered over 100 of these densely-spaced settlements in the low-lying region, which appear to have relied on adjacent waterways and wetlands for resources.

That might have helped these people postpone some of the climate-related impacts that catalyzed the collapse of other Late Bronze Age settlements, although by around 1250 BCE the lack of rain began to take its toll on these wetland-oriented societies.

By 1200 BCE, virtually all of these sites were abandoned en masse.

“It is fascinating to discover these new polities and to see how they were related to well-known influential societies yet sobering to see how they ultimately suffered a similar fate in a wave of crises that struck this wider region,” says Molloy.

These societies challenge many aspects of European prehistory, and appear to have been an important center of innovation, politics and trade during 1500–1200 BCE.

The researchers describe these communities as mutually dependent and closely interwoven, operating at a near total-landscape level, with complex social institutions and attendant power structures to manage interaction, cooperation, competition, and violence.

“[We] have been able to define an entire settled landscape, complete with maps of the size and layout of sites, even down to the locations of people’s homes within them,” Molloy said.

“This really gives an unprecedented view of how these Bronze Age people lived with each other and their many neighbors.”

The research was published in PLOS ONE.