Both bar charts and line charts are designed to help us visualize data. They are tools to transform numerical information into pictorial narratives that are easier to understand. You do not change the data; they just represent it.

However, they present it in different ways, and even these slight differences may be enough to influence our attempt predictionsfor a new one learn.

Researchers from the UK recruited more than 4,000 subjects via the internet, presented them with various graphs depicting past sales of a fictional company and asked them to predict future sales based on past trends.

Participants consistently made lower predictions about how a trend in the data would develop when the data was presented in a bar chart, as opposed to the same data presented with either a line chart or disconnected dots on a chart, the researchers said Study.

Graphics like these play a key role in society, says lead author Stian Reimers, a behavioral scientist at the City, University of London. As a window into complex data, visualizations help more people understand important topics – or at least that’s the idea.

“In the past few years, it seems like we’ve spent a lot of time looking at time series: whether it’s the number of COVID-19 Cases, electricity prices or inflation rates to find out what’s next,” said Reimers says.

“What our research shows is that our predictions of what we think will happen next aren’t just influenced by the trends we’re looking at,” he said adds“but the format in which they are displayed.”

Reimers and co-author Nigel Harvey, a cognitive psychologist who studies judgment and decision-making at University College London, recruited subjects using an internet rewards program that encouraged participants to complete the two-minute online experiment and make accurate predictions.

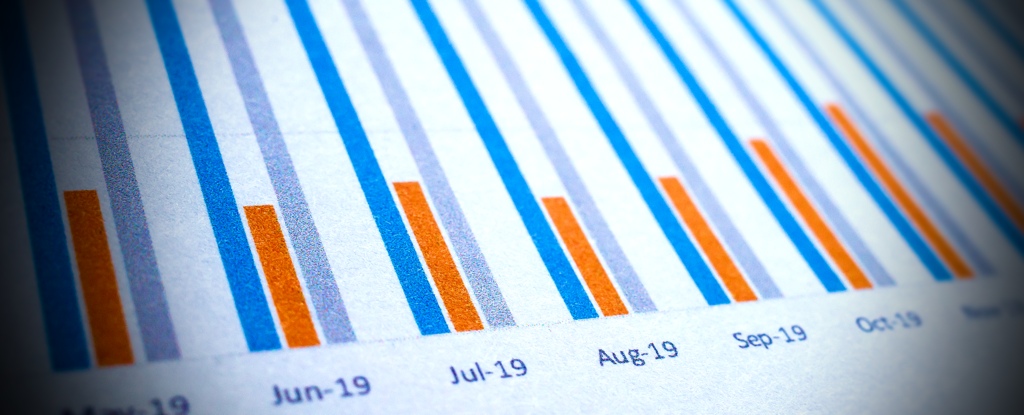

In the study’s first two experiments, researchers gave subjects a single chart — either a bar, line, or scatter chart — with 50 data points representing total sales. The subjects could then click on the chart to record their prediction for the next 8 sales periods.

The first experiment featured a graph showing increases in sales over time, which generally led subjects to predict continued success. The second experiment attempted the opposite, with a chart showing decreases over time, and subjects responded with more pessimistic forecasts.

Across a variety of trends, subjects consistently made lower predictions of future sales when the same data was presented with a bar chart rather than a line or scatter chart.

Hoping to elucidate the reason for this, the researchers tried to adjust the appearance of the bars themselves. Perhaps heavily shaded bars draw people’s attention down and skew it by associating the actual data points with the prominent shaded area below?

However, the researchers found that the subjects continued to hold the bar graphs low even when the bars were unshaded.

A recent experiment suggested that the bias might be reversible if the bars emanate from the top rather than the bottom of the chart, but the results were inconclusive, the researchers report.

Having this bias in place could create problems in a number of ways, Reimers points out. For example, it could lead people to misunderstand local COVID-19 or flu activity before visiting a vulnerable relative, or misjudge whether they can afford a mortgage.

Similar mistakes could have even broader implications in a business or political context, the researchers note, particularly in situations where a person “looks at” a chart to make rough guesses about what’s going to happen next.

A bias like this could potentially be used to mislead people, although there are two sides to this coin. By understanding bias and how it works, we may be better able to accurately present data and help a larger audience understand it.

”Many of the other biases that people display when they try to extrapolate trends are ingrained in our view of the world and are difficult to change,” says Reimers explained.

“The format that we use for our charts is something that we have complete control over, so it may be possible to use certain formats to undo people’s built-in biases and help people find more accurate ones.” to make judgments,” he says.

The study was published in International Journal of Forecasts.