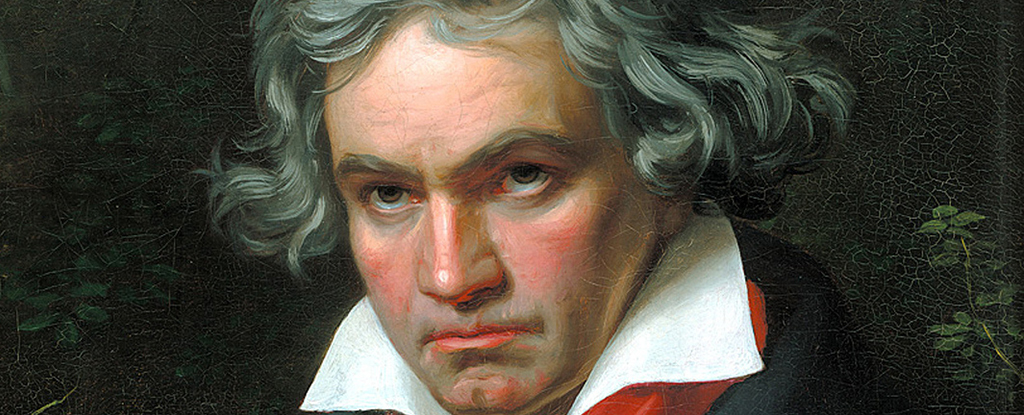

A centuries-old lock of hair that turned out to be from an unknown woman and advanced genomic sequencing technologies in 2023 debunked a long-running theory that German composer Ludwig van Beethoven had died from lead poisoning.

Instead, on a stormy day, wracked with jaundice, the famed pianist succumbed to what is believed to be liver disease brought on by a hepatitis B infection, worsened by his drinking habits and seeded by genetic risk factors.

But for all the interest in how Beethoven died, researchers were still unsure what caused his gastrointestinal problems and progressive hearing loss throughout his life. Distraught by their onset, Beethoven somehow managed to compose orchestral symphonies that are revered to this day, although his hearing loss forced him to withdraw from public and stop performing.

Now, a new investigation of two locks of hair previously authenticated as Beethoven’s own has confirmed that the composer really was likely suffering the effects of lead poisoning – although the exposure was not enough to kill him.

Nader Rifai, a pathologist at Harvard Medical School, and colleagues analyzed the two hair bundles, known as the Bermann and the Halm-Thayer locks, which had been authenticated in the 2023 genetic analysis.

For an added layer of certainty for skeptical minds, the Halm-Thayer lock is one of only two where historians know it was sourced by Beethoven himself; records show the composer hand-delivered the lock to pianist Anton Halm in April 1826.

Using clinically-validated mass spectrometry methods, Rifai and colleagues measured the amount of lead, as well as arsenic and mercury, in the two hair locks, which had first been washed and dried to minimize contamination through handling and storage.

The Bermann lock had a lead concentration 64 times higher than the upper limit of what’s considered typical for an otherwise healthy person, while the Halm-Thayer lock had a lead concentration 95 times greater than that reference range. Levels of arsenic and mercury were also high.

From the lead levels in the 19th century hair samples, the researchers then estimated that Beethoven’s blood lead concentration could have been between 69 to 71 micrograms per deciliter (µg/dL).

“Such lead levels are commonly associated with gastrointestinal and renal ailments and decreased hearing but are not considered high enough to be the sole cause of death,” Rifai and colleagues write in their short letter to the editor of Clinical Chemistry.

Beethoven’s exposure to lead is easily explained by the culture of drinking from lead vessels and medical treatments involving lead used in Beethoven’s time. The new measurements, from verified samples, give us greater confidence in how that lead exposure likely affected his health.

“While the concentrations determined are not supportive of the notion that lead exposure caused Beethoven’s death, it may have contributed to the documented ailments that plagued him most of his life,” the researchers conclude.

Measuring hair lead levels might not be a good indicator of blood concentrations though, and there are some other possibilities that could explain Beethoven’s hearing loss, which other researchers have considered.

The 2023 genetic analysis revealed that Beethoven had a few genetic markers linked to lupus, a rare condition that can sometimes lead to hearing loss.

Medical historians have also wondered if Beethoven’s middle ear bones had fused together, which happens with a condition called otosclerosis. But the genetic causes of otosclerosis are not yet known, so it remains an open mystery that could be revisited if genetic links are identified in the future.

“Like all good stories, it leaves us with as many questions as answers,” Walther Parson, a forensic molecular biologist at the Medical University of Innsbruck in Austria, said of Beethoven’s case in 2023.

The research has been published in Clinical Chemistry.