If you’re fascinated by Nature, these images of spiral galaxies won’t help you escape your fascination.

These images show incredible detail in 19 spirals, imaged face-on by the JWST. The galactic arms with their multitudes of stars are lit up in infrared light, as are the dense galactic cores, where supermassive black holes reside.

The JWST captured these images as part of the Physics at High Angular resolution in Nearby GalaxieS (PHANGS) programme. PHANGS is a long-running program aimed at understanding how gas and star formation interact with galactic structure and evolution.

One of Webb’s four primary science goals is to study how galaxies form and evolve, and the PHANGS program feeds that effort. The VLT, ALMA, the Hubble, and now the JWST have all contributed to it.

“Webb’s new images are extraordinary. They’re mind-blowing even for researchers who have studied these same galaxies for decades.”

Janice Lee, Project Scientists, Space Telescope Science Institute.

The JWST can see in both near-infrared (NIR) and mid-infrared (MIR) light. That means it reveals different details, and more details, than even the powerful Hubble Space Telescope, which operates in visible light, UV light, and a small portion of infrared light.

In these JWST high-resolution images, the red color is gas and dust emitting infrared light, which the JWST excels at seeing. Some of the images have bright diffraction spikes in the galactic center, which are caused by an enormous amount of light.

That can indicate that a supermassive black hole is active, or it could be from an extremely high concentration of stars.

“That’s a clear sign that there may be an active supermassive black hole,” said Eva Schinnerer, a staff scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. “Or, the star clusters toward the center are so bright that they have saturated that area of the image.”

Stars near a galaxy’s center are typically much older than stars in the arms. The further a star is from the galactic center, the younger it typically is. The younger stars appear blue and have blown away the cocoon of gas and dust that they spawned in.

Orange clumps indicate even younger stars. They’re still wrapped in their blanket of gas and dust and are still actively accreting material and forming.

“These are where we can find the newest, most massive stars in the galaxies,” said Erik Rosolowsky, a professor of physics at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada.

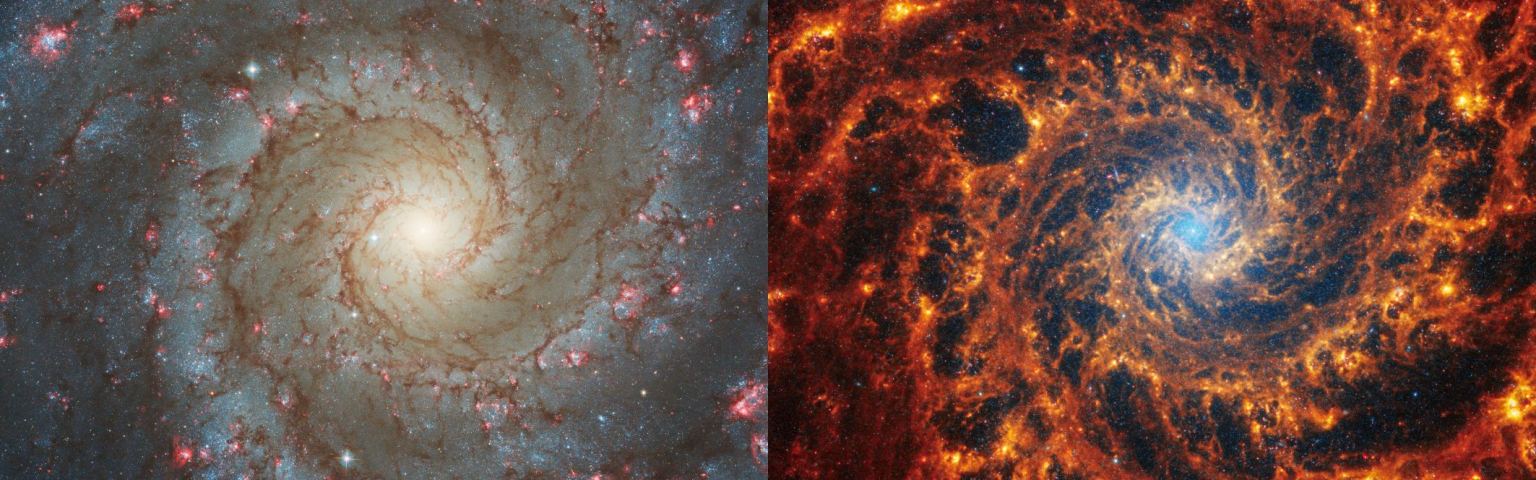

The new images were released alongside some of the Hubble’s views of the same galaxies. These highlight how observing different wavelengths of light reveals or obscures different details in the galaxies. In the PHANGS observing program, different telescopes have observed galaxies in visible light, infrared light, UV light, and radio.

Since the human eye can’t see infrared, different visible colors are assigned to different wavelengths of light in order to make the images meaningful. In the JWST image of NGC 628 above, the galaxy’s center is filled with old stars that emit some of the shortest wavelengths of light the telescope can detect. They’ve been given a blue color to make them visible.

In the Hubble image, the same region is more yellow and washed out. The region emits the longest wavelengths of light that the Hubble can sense, so it has different color assignments than the JWST.

Janice Lee is a project scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

She spoke for all of us when she said, “Webb’s new images are extraordinary. They’re mind-blowing even for researchers who have studied these same galaxies for decades. Bubbles and filaments are resolved down to the smallest scales ever observed and tell a story about the star formation cycle.”

These galaxies are all spiral galaxies like the Milky Way, meaning their massive arms define them. The spiral arms are more like waves that travel through space rather than individual stars moving collectively. Astronomers study the arms because they can provide key insights into how galaxies build, maintain, and shut off star formation.

“These structures tend to follow the same pattern in certain parts of the galaxies,” Rosolowsky added. “We think of these like waves, and their spacing tells us a lot about how a galaxy distributes its gas and dust.”

Ever since it began science operations, the JWST has given astronomers an overwhelming flow of data that will fuel research for years and decades to come. These beautiful images are just a part of a larger data release that includes a catalogue of about 100,000 star clusters.

“The amount of analysis that can be done with these images is vastly larger than anything our team could possibly handle,” said the University of Alberta’s Erik Rosolowsky. “We’re excited to support the community so all researchers can contribute.”

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.