Children in the United States are increasingly suffering from persistent or severe health conditions, many of which are preventable and could follow them into adulthood, according to new research.

The findings come from a long-term survey of more than 230,000 young people, whose families reported whether they had any chronic conditions, like asthma, or functional limitations, like attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

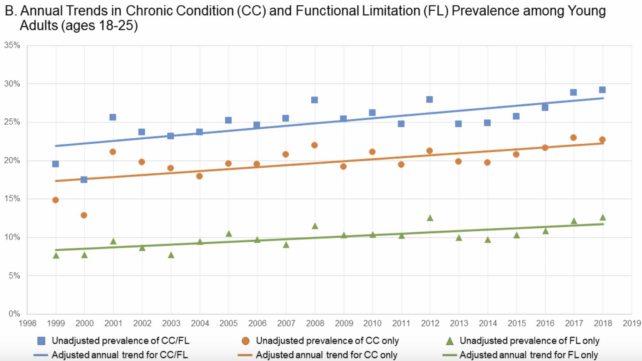

According to the results, the percentage of kids who are dealing with any of these conditions or limitations has risen from nearly 23 percent in 1999 to just over 30 percent in 2018.

That’s nearly one in three young people who are now thought to be living with severe or activity-limiting health concerns.

In children aged 5 to 17, the survey’s data suggests the jump in chronic conditions is mainly due to ADHD/ADD, autism, and asthma. For young adults between 18 and 25, on the other hand, the increase is largely because of asthma, seizures or epilepsy, and pre-diabetes.

Rising functional limitations in children, meanwhile, were primarily driven by speech conditions, musculoskeletal issues, depression, anxiety, emotional problems, or other mental health conditions.

Because some of these conditions are preventable, the results hint at an overlooked and underserviced population.

“We estimate that there are currently 87.4 million youth ages 5 and 25 in the US, of which 25.7 million reported any chronic condition or functional limitation,” write the authors of the study, Lauren Wisk, who studies health services at the University of California Los Angeles, and pediatrician Niraj Sharma from Harvard University.

“This amounts to 1.2 million youth with a chronic condition or functional limitation who currently turn 18 each year.”

That’s a lot of children who will need ongoing care as they grow older. Past studies suggest, however, that doctors in the US are poorly prepared to treat rising conditions of childhood origin.

In a paper from 2014, researchers wrote that when transitioning from pediatric to adult-centered health care, “many youth do not receive the age-appropriate medical care they need and are at risk during this vulnerable time.”

Figuring out what is actually driving these upward trends in pediatric chronic conditions will require much more detailed research. There are likely numerous factors at play, including a “complex interaction of individual biology, community context and environment, and health care systems,” explain Wisk and Sharma.

When the two co-authors carefully accounted for a whole variety of socioeconomic variables that may be influencing their results, they found substantial disparities.

Kids with chronic illnesses were more likely to be poor, unemployed, or have public, not private, insurance.

“Most youth with chronic conditions need to access health and social services for the rest of their lives, but our health system is not set up to successfully move young people from pediatric to adult focused care and so many of these youth are at risk of disengaging with care and experiencing disease exacerbations,” explains Wisk.

“We should invest in assisting these youth in engaging appropriately with healthcare across their lifespan in order to protect their health and well-being, and to facilitate their maximum participation in society with respect to education, vocation, social groups, and community spaces.”

Unfortunately, as of 2019, the same survey used in the current study – called the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) – no longer asks as many detailed questions related to chronic conditions.

This makes it harder to gauge where we are headed, or how the 2020 pandemic impacted childhood mental and physical health.

“This means we no longer have the ability to track and analyze trends in chronic health conditions in youth past that date,” says Wisk. “We need to find creative new ways to continue to monitor the health of our nation’s youth if we want to further study this population.”

The study was published in Academic Pediatrics.