Researchers have detected a cluster of lost 2,500-year-old cities at the foothills of the Andes in the Amazon rainforest.

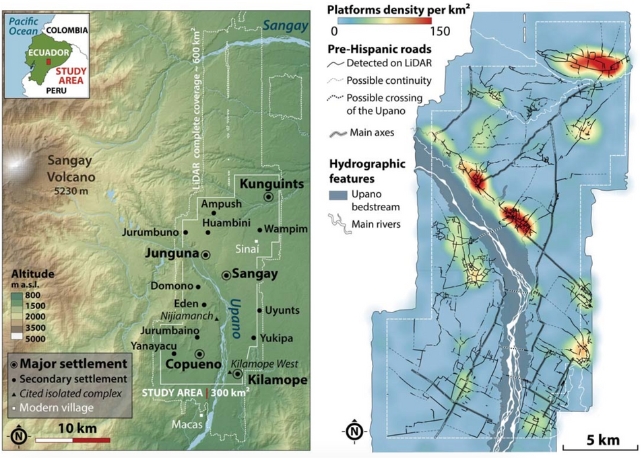

This amazing discovery, the oldest and largest of its kind in the region, includes a vast system of farmland and roads, revealing that Ecuador’s Upano Valley was densely populated from about 500 BCE to between 300 and 600 CE.

Led by French National Center for Scientific Research archaeologist Stéphen Rostain, a multi-national team analyzed data from more than two decades of interdisciplinary research in the region, recently expanded by light detection and ranging (LIDAR) mapping.

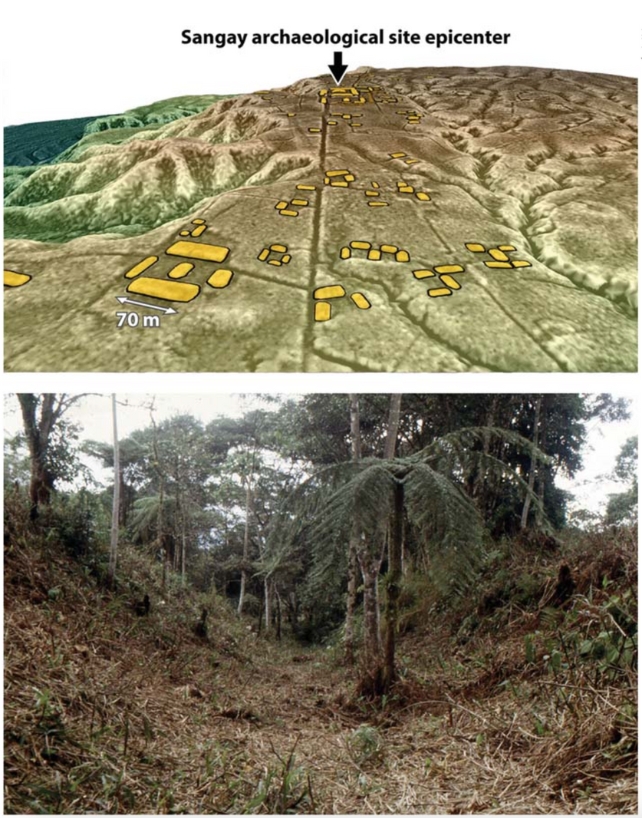

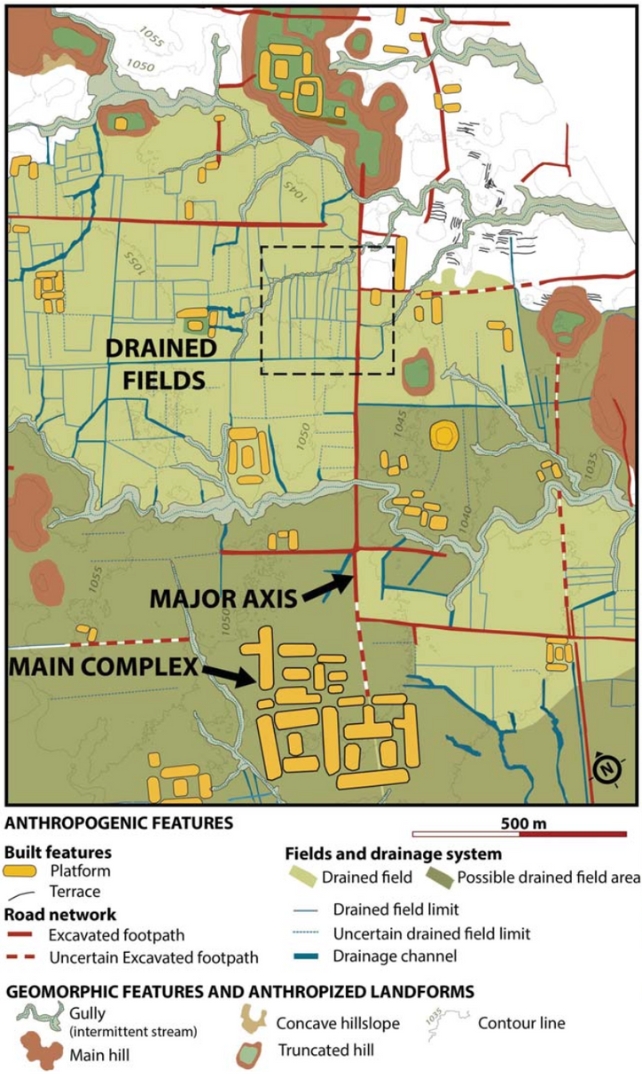

Covering an area of 300-square-kilometers (115-square-miles), LIDAR mapped platforms, plazas, and streets arranged in a geometric pattern, interwoven with agricultural drainage, terraces, and incredibly long, straight roads that connected a number of urban sites.

“This research revealed the largest urban network of erected and excavated features known in Amazonia, whose beginnings date back to 2,500 years ago,” writes the team in their published paper.

“The Upano sites are quite different from other monumental sites of Amazonia, which are all more recent.”

Using the ‘echoes’ of laser pulses consisting of various wavelengths of light, LIDAR can measure the distance between an aircraft and ground objects, crafting a 3D map that can reveal hidden features of the terrain beneath dense vegetation.

It’s a powerful tool that’s already exposed concealed Maya settlements and described the layouts of ancient villages deep within the Amazon’s greenery.

Evidence of a vast, pre-Hispanic human influence in the Amazon continues to grow, with the current coverage of LIDAR data suggesting more than 90 percent of the human history in the Amazon is yet to be uncovered.

Under the canopy of trees in the Upano Valley, Rostain and team detected residential and ceremonial buildings built on over 6,000 earthen platforms, clustered into 15 settlements linked by an intricate road system.

The platforms were mostly rectangular, with a few circular exceptions, and measured about 20 meters by 10 meters (66 feet by 33 feet). They were usually constructed in clusters of three or six around a plaza, with a central platform in the middle.

To form a network of straight roads, soil was dug out and piled on the sides. The longest road stretches for at least 25 kilometers, and possibly further beyond the research area’s borders.

Some settlements were small, with just a few platforms per square kilometer, but others, such as Sangay, which overlooks most of the valley, packed more than 100 platforms into each square kilometer, and closer inspection unearthed impressive detail.

“Large-scale excavations in platforms and plazas at two major settlements (Sangay and Kilamope) revealed domestic floors, with post-holes, caches, pits, hearths, large jars, grinding stones, and burnt seeds,” Rostain and colleagues write.

The LIDAR data didn’t stop at uncovering ancient settlements; it revealed that the open spaces between settlements were drained fields for cultivating crops like maize, beans, sweet potatoes, and cassava – a woody shrub with starchy root tubers.

The organization of the cities reveals the sophistication and engineering capabilities of these ancient cultures, according to the researchers, who concluded that the ‘garden urbanism’ of the Upano Valley provides further proof that Amazonia is not the pristine forest once depicted.

“Such a discovery is another vivid example of the underestimation of Amazonia’s twofold heritage: environmental but also cultural, and therefore Indigenous,” the authors write.

“We believe that it is crucial to thoroughly revise our preconceptions of the Amazonian world.”

The study has been published in Science.