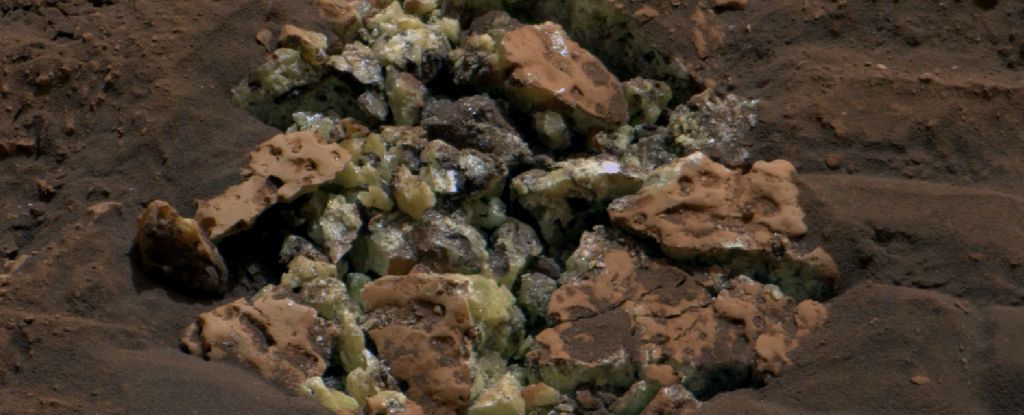

A rock on Mars has just spilled a surprising yellow treasure after Curiosity accidentally cracked through its unremarkable exterior.

When the rover rolled its 899-kilogram (1,982-pound) body over the rock, the rock broke open, revealing yellow crystals of elemental sulfur: brimstone. Although sulfates are fairly common on Mars, this is the first time sulfur has been found on the red planet in its pure elemental form.

What’s even more exciting is that the Gediz Vallis Channel, where Curiosity found the rock, is littered with rocks that look suspiciously similar to the sulfur rock before it got fortuitously crushed – suggesting that, somehow, elemental sulfur may be abundant there in some places.

“Finding a field of stones made of pure sulfur is like finding an oasis in the desert,” says Curiosity project scientist Ashwin Vasavada of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“It shouldn’t be there, so now we have to explain it. Discovering strange and unexpected things is what makes planetary exploration so exciting.”

Sulfates are salts that form when sulfur, usually in compound form, mixes with other minerals in water. When the water evaporates, the minerals mix and dry out, leaving the sulfates behind.

These sulfate minerals can tell us a lot about Mars, such as its water history, and how it has weathered over time.

Pure sulfur, on the other hand, only forms under a very narrow set of conditions, which are not known to have occurred in the region of Mars where Curiosity made its discovery.

There are, to be fair, a lot of things we don’t know about the geological history of Mars, but the discovery of scads of pure sulfur just hanging about on the Martian surface suggests that there’s something pretty big that we’re not aware of.

Sulfur, it’s important to understand, is an essential element for all life. It’s usually taken up in the form of sulfates, and used to make two of the essential amino acids living organisms need to make proteins.

Since we’ve known about sulfates on Mars for some time, the discovery doesn’t tell us anything new in that area. We’re yet to find any signs of life on Mars, anyway. But we do keep stumbling across the remains of bits and pieces that living organisms would find useful, including chemistry, water, and past habitable conditions.

Stuck here on Earth, we’re fairly limited in how we can access Mars. Curiosity’s instruments were able to analyze and identify the sulfurous rocks in the Gediz Vallis Channel, but if it hadn’t taken a route that rolled over and cracked one open, it could have been some time since we found it.

The next step will be to figure out exactly how, based on what we know about Mars, that sulfur may have come to be there. That’s going to take a bit more work, possibly involving some detailed modeling of Mars’s geological evolution.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

Meanwhile, Curiosity will continue to collect data on the same. The Gediz Vallis channel is an area rich in Martian history, an ancient waterway whose rocks now bear the imprint of the ancient river that once flowed over them, billions of years ago.

Curiosity has drilled a hole in one of the rocks, taking a powdered sample of its interior for chemical analysis, and is now trundling its way deeper along the channel, to see what other surprises might be waiting just around the next rock.