Bone artifacts discovered in Tanzania push back the earliest known date of bone tool technology by over a million years.

In Olduvai Gorge, archaeologists have discovered a range of bone tools thought to have been made and used by an ancestral human species of hominid called Homo habilis 1.5 million years ago.

Known as the Oldowan people, the culture responsible for the bone artifacts was already known for their use of stone tools dating back to 2.5 million years ago. The newly identified bone artifacts show that their tool technology was more complex, advanced, and sophisticated than we knew.

“This discovery leads us to believe that early humans expanded significantly their technological choices, which until this moment was constrained to production of stone artifacts, and now enabled incorporating new raw materials to the repertoire of potential tools,” says archaeologist Ignacio de la Torre of the Spanish National Research Council.

“Additionally, this enhancement of the technological potential hints at advances in the cognitive capacities and mental templates of these hominins … who understood how to transfer technical innovations from stone flaking to bone tool production.”

The development of tool technology is considered a pivotal step in human evolution. Deliberately shaped stones are thought to have emerged in cultures more ancient than our own genus Homo to strip more marrow and meat from kills, which in turn may have played a key role in our own evolutionary success.

Archaeological evidence that early humans figured out to craft tools from the bones of the animals they ate, however, was pretty thin on the ground, restricted to specific sites in Europe a mere 400,000 to 250,000 years ago.

Some earlier sites had fragments of horn or longer bones that had been used as tools for digging, but there was no evidence that these had been deliberately altered in any way.

This lack of identifying marks has made it difficult to establish how tools based on organic remains are produced. It also makes it hard to track their use and study regional variations in bone tool technology.

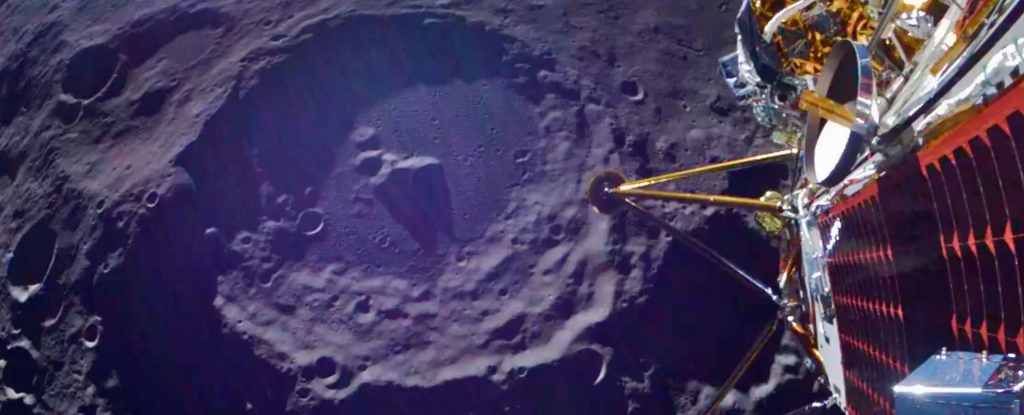

Between 2015 and 2022, archaeological excavations were conducted in Olduvai Gorge, where the Oldowan culture had its seat from around 2.6 million to 1.5 million years ago. Artifacts recovered from digs often include animal remains, so seeing some bones among the thousands of stone artifacts wasn’t a surprise.

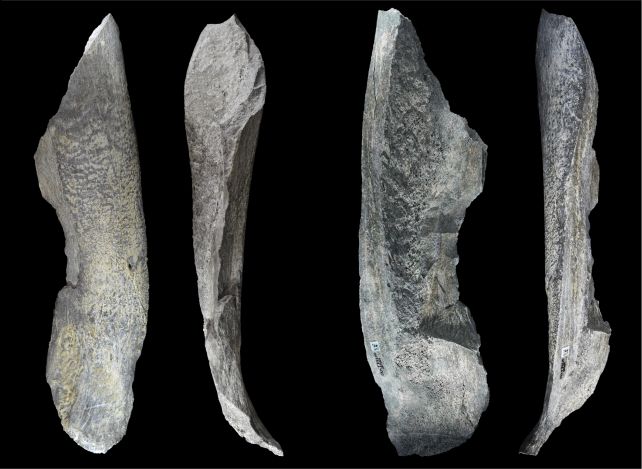

When the archaeologists looked more closely at some of the bones recovered from a buried layer dated to 1.5 million years ago, though, they were blown away. Twenty-seven of the bones showed signs of having been altered: deliberately broken and flaked (or knapped) to create sharp, heavy-duty tools.

This suggests that bone tool manufacture may have played a part in the technological transition from the Oldowan culture to the Acheulean culture that followed it, which started around 1.7 million years ago and came to a close around 150,000 years ago.

“Prior to our discovery, the technological transition from the Oldowan to the Acheulean was limited to the study of stone tools,” de la Torre explains.

“Our discovery indicates that, from the Acheulean period in which the T69 Complex site was formed and where humans already had a primary access to meaty resources, no longer were animals only dangerous, competitors, or just foodstuff, but also a source of raw materials for producing tools.”

The tools mostly consist of elephant and hippopotamus bones. What they were used for is unknown, although the research team suggests the bones may have been employed for butchering, later phased out by more effective heavy-duty stone tools as technology continued to develop.

As for how bone tool technology may have changed, spread, or even died out before reappearing over a million years later in another part of the world, we don’t know. It’s possible future excavations will uncover more tools hiding in the fossil record. Whatever the answer is, it’s going to take more work to find it.

One thing’s for sure. There’s a lot more to our human ancestors than meets the eye.

“By producing technologically and morphologically standardized bone tools, early Acheulean toolmakers unraveled technological repertoires that were previously thought to have appeared routinely more than 1 million years later,” de la Torre says.

“This innovation may have had a significant impact on the complexification of behavioral repertoires among our ancestors, including enhancements in cognition and mental templates, artifact curation, and raw material procurement.”

The research has been published in Nature.