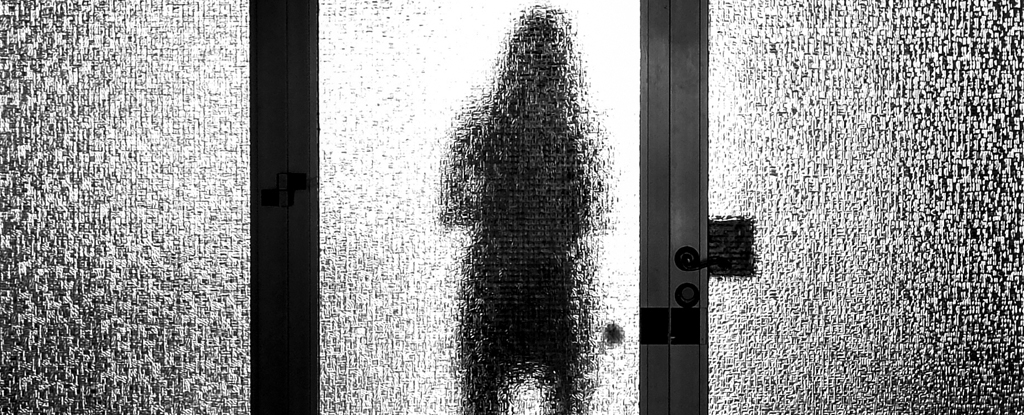

If you’ve ever had the eerie feeling that there’s a presence in the room, even though you were sure you were alone, you might be reluctant to admit it.

Perhaps it was a profound experience that you are happy to share with others.

Or – more likely – it was something in between.

If you didn’t have an explanation to help you process the experience, most people will have trouble understanding what happened to them.

But now research shows that this ethereal experience is something we can understand using scientific models of the mind, the body, and the relationship between the two.

One of the largest studies on this subject was conducted as early as 1894. The Society for Psychical Research (SPR) published theirs Hallucination count, a survey of more than 17,000 people in the UK, US and Europe. The survey aimed to understand how common people had seemingly impossible visits that predicted death.

The SPR concluded that such experiences happened too often to be due to chance (one in 43 people interviewed).

In 1886 the SPR (which counted former British Prime Minister William Gladstone and poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson among its patrons) published phantasms of the living. This collection included 701 cases of telepathy, premonitions, and other unusual phenomena.

For example, Reverend PH Newnham of Devonport in Plymouth related the story of a visit to New Zealand where a nighttime presence warned him not to join a dawn boat trip the next morning. He later learned that everyone had drowned on the voyage.

At the time, phantasms were criticized as unscientific. The census was met with less skepticism, but still suffered from response bias (who would bother to respond to such a poll except those with a say).

But such experiences live on in homes around the world, and contemporary science offers ideas for understanding them.

Not so sweet dreams

Many of the reports SPR has collected sound like hypnagogia: hallucinatory experiences that happen on the verge of sleep. It has that was suggested Several religious experiences recorded in the 19th century have a basis in hypnagogia.

Presences have a particularly strong association with sleep paralysis, experienced by about 7 percent of adults at least once in their life. In sleep paralysis, our muscles remain frozen like a hangover from REM sleep, but our minds are active and alert. studies have suggested More than 50 percent of people with sleep paralysis report encountering a presence.

While the Victorian presences documented by the SPR were often benign or reassuring, modern examples of presences induced by sleep paralysis tend to exude malevolence.

Societies around the world have their own tales of nocturnal presences – from the Portuguese “little monk with the pierced hand” (Fradinho da Mao Furada) that could infiltrate people’s dreams, to the Ogun Oru of the Yoruba people of Nigeria, believed to have been a product of sacrifices being bewitched.

But why should an experience like paralysis create a sense of presence? Some researchers have focused on the specific characteristics of waking up in such an unusual situation. Most people find sleep paralysis scary, even without hallucinations.

2007 Sleep Researcher J Allen Cheyne and Todd Girard argued that when we wake up paralyzed and vulnerable, our instincts feel threatened and our minds fill the void. If we are prey, there must be a predator.

Another approach is to explore the similarities between sleep paralysis visits and other types of sensed presence. Research over the past 25 years has shown that presences are not only an integral part of the hypnagogic landscape, they are also reported on Parkinson’s disease, psychosis, near-death experiences and grief. This suggests that it is unlikely to be a sleep-specific phenomenon.

mind-body connection

We know from neurological case studies And brain stimulation experiments that presences can be provoked by bodily signals.

For example, in 2006, neurologist Shahar Arzy and his colleagues managed to create a “shadow figure” experienced by a woman whose brain was electrically stimulated in the left temporoparietal junction (TPJ). The figure appeared to mirror the woman’s posture – and the TPJ brings together information about our senses and our bodies.

A series of experiments in 2014 also showed that disrupting people’s sensory expectations seems to work create a sense of presence in some healthy people. The method used by the researchers is to make you feel like you’re touching your own back by synchronizing your movements with a robot right behind you.

Our brain makes sense of the sync by inferring that we are creating that sensation. Then, when that sync is broken — by causing the robot’s touches to be slightly out of sync — humans can suddenly feel like another person is present: a ghost within the machine. The change in sensory anticipation of the situation triggers something akin to a hallucination.

This logic could also apply to a situation like sleep paralysis. All of our usual information about our bodies and senses is disrupted in this context, so perhaps it’s not surprising that we feel like there’s something “other” about us. We may feel like another presence, but in fact we are.

In my own research in 2022 I tried to explore the similarities in presences from clinical reports, spiritual practice and endurance sports (which are known for produce a range of hallucinatory phenomenaincluding presence).

In all of these situations, many aspects of the sense of presence were very similar: for example, the person felt directly behind them. Sleep-related presences were described by all three groups, but also presences triggered by emotional factors such as sadness and grief.

Despite its centuries-old origins, the science of sensed presence is only just beginning. In the end, scientific research can give us an overarching explanation, or we need multiple theories to explain all these examples of presence.

But the human encounters described in Phantasms of the Living are not phantoms of a bygone age. If you haven’t had this unsettling experience, chances are you know someone who has.

Ben Alderson DayAssociate Professor of Psychology, University of Durham

This article is republished by The conversation under a Creative Commons license. read this original article.