A koala on a hot day in the Australian outback nestles against the cool branches of a eucalyptus while a wombat hides underground in his burrowand a kangaroo spits on his wrists to cool his blood vessels. Closer to the coast, a Fur seal on the rocks pees on his fins.

The echidna is different. Does not sweat, gasp, lick, or urinate on itself to cool itself. But what it can do is blow wet snot bubbles out of its nose. And that ability has been seriously underestimated.

Researchers at Curtin University in Australia have shown that this prickly cloaca uses booger-like exhalations to lower its body temperature. The findings are based on the short-beaked hedgehog (Tachyglossus aculeatus), but there is a possibility that the chilling technique is also used by other Echidna species.

“Echidnas blow bubbles from their noses, which burst over the tip of their nose and wet them,” explained Ecophysiologist Christine Cooper from Curtin University in Australia.

“As the moisture evaporates, it cools her blood, which means the tip of her nose acts as an evaporation window.”

Scientists have long wondered how echidnas manage to survive in Australia’s hot climate. Previous studies in the laboratory have shown that echidnas have a relatively low heat tolerance and should not survive temperatures above 35 °C (95 °F).

And yet they do. Short-beaked echidnas have been seen Shelter in hollow logs that are 40°C warm.

How do you stand it?

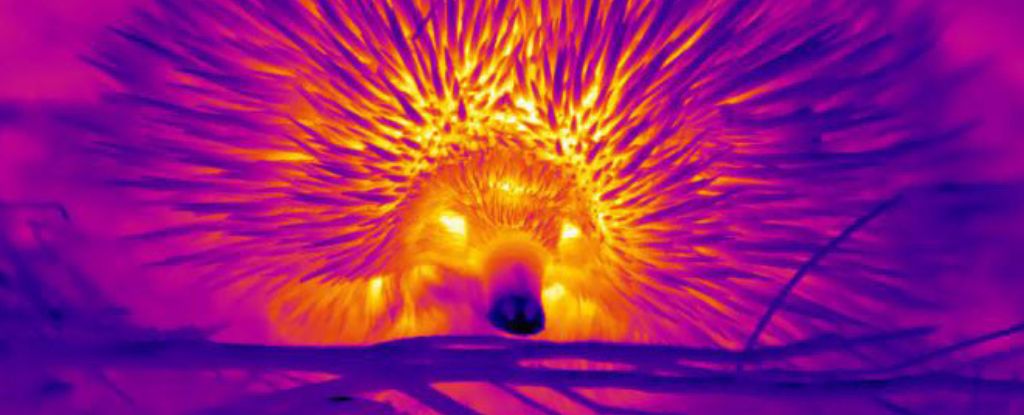

Curtin’s team discovered some intriguing ways monotremes cool themselves. At least once a month over the course of a year, the researchers measured the temperatures of 124 short-beaked echidnas in the wild using infrared thermal imaging cameras. The team also recorded each echidna’s ambient temperature.

The authors have measured ground temperatures as high as 47°C at some times of the year and in some parts of Western Australia. But the body temperature of the echidnas studied remained constantly below 30°C.

The ears were usually the hottest part of the monotreme’s body. The tip of their beak (or nose), the coolest.

In the infrared images below, the cool surfaces stand out in bluish purple, while the hottest surfaces range from red to orange to yellow.

The colorful heat map suggests that echidnas store heat in their spines and shed heat from their stingless areas, such as their abdomen and legs.

To give off heat, the animal simply has to “open” its underparts to the air or press them against the cool ground. The tip of the beak works differently. Under infrared light it looks almost like a small blue Rudolph nose, reflecting its relative coolness.

Based on echidna physiology, researchers know that just below the surface of the tip of the beak lies a sinus cavity filled with blood vessels. Much like when a kangaroo licks its wrists, the echidna essentially sheds excess body heat in its blood by evaporating the moisture on its nose.

“We identify the beak tip of short-beaked echidnas as a unique type of evaporation window,” the Curtin researchers said conclude.

“In the climax [temperatures] Echidna blows mucous sacs and adds moisture to the tip of the beak.”

Nobody said that surviving in Australia’s harsh wilderness is a beautiful job. Blowing a few boogers to beat the midday heat is better than peeing on your hands every day.

The study was published in biology letters.