Dominated by carbon-rich swamps and forests proliferating across Earth’s rocky surface, the Carboniferous period saw a boost in atmospheric oxygen and vast quantities of carbon dioxide trapped in what eventually became Earth’s coal deposits. Terrestrial plant and animal life flourished amid these changes.

But we’ve long been missing the earliest part of that picture, with most of our knowledge on this critical stage of Earth’s evolutionary past coming from layers of coal-bearing swamp deposits formed between 315 and 307 million years ago, representing the Middle Pennsylvanian period.

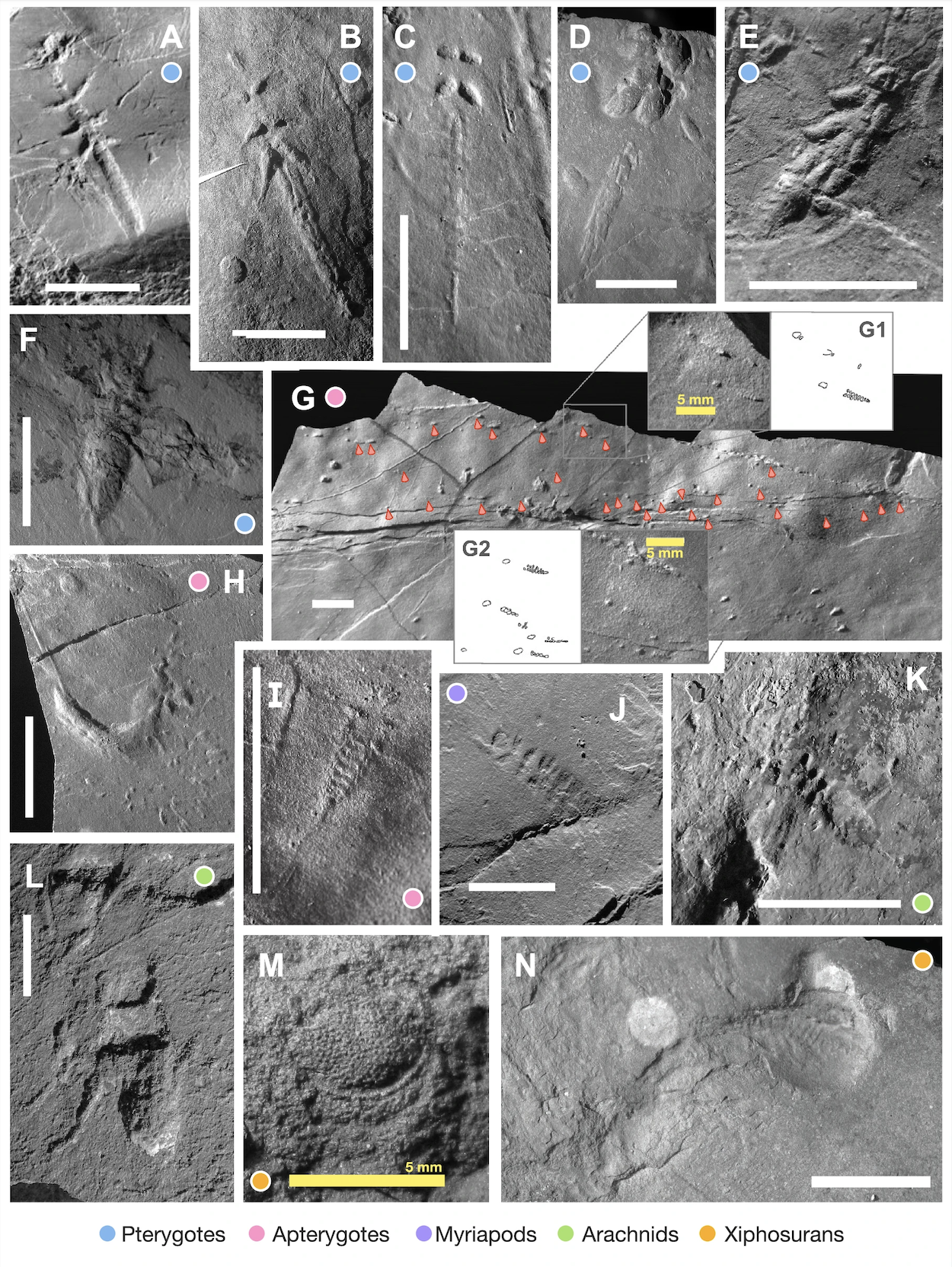

Now, an international team has discovered an entire ecosystem preserved in sedimentary stone from the Early Pennsylvanian (a period from around 320 to 318 million years ago), containing more than a hundred different organisms.

The fossil site, dubbed Lantern North, was discovered in eastern North America within the Wamsutta Formation.

Its geological profile is distinct from other Pennsylvanian-era sites, being formed from broken-up pieces of older rocks. Lantern North is also a time capsule of a drier, upland environment that contains records of the daily lives of tetrapod, arthropod, and seed plant groups at a time when terrestrial environments – and the creatures that had recently expanded into them – were changing rapidly.

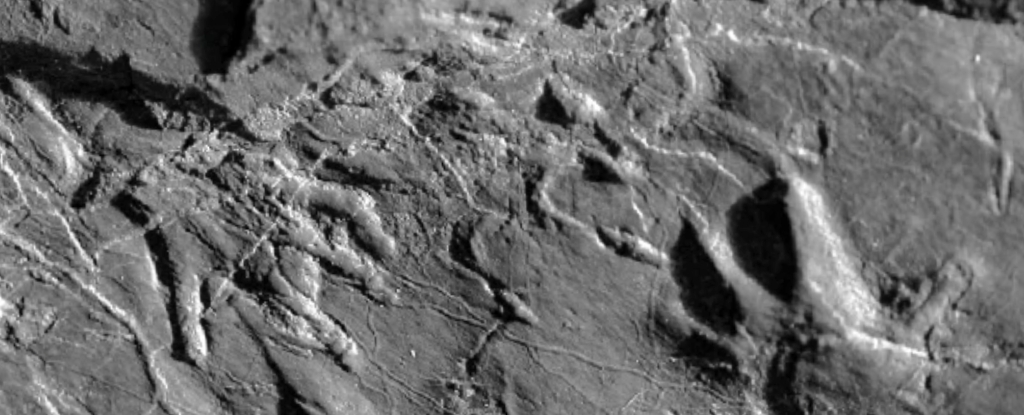

Coarse layers of sedimentary rock interspersed with fossil-rich, oxidized-red wafers of sandstone shale form a basin which had been laid before the period’s signature carbonaceous deposits filled in a swampy center.

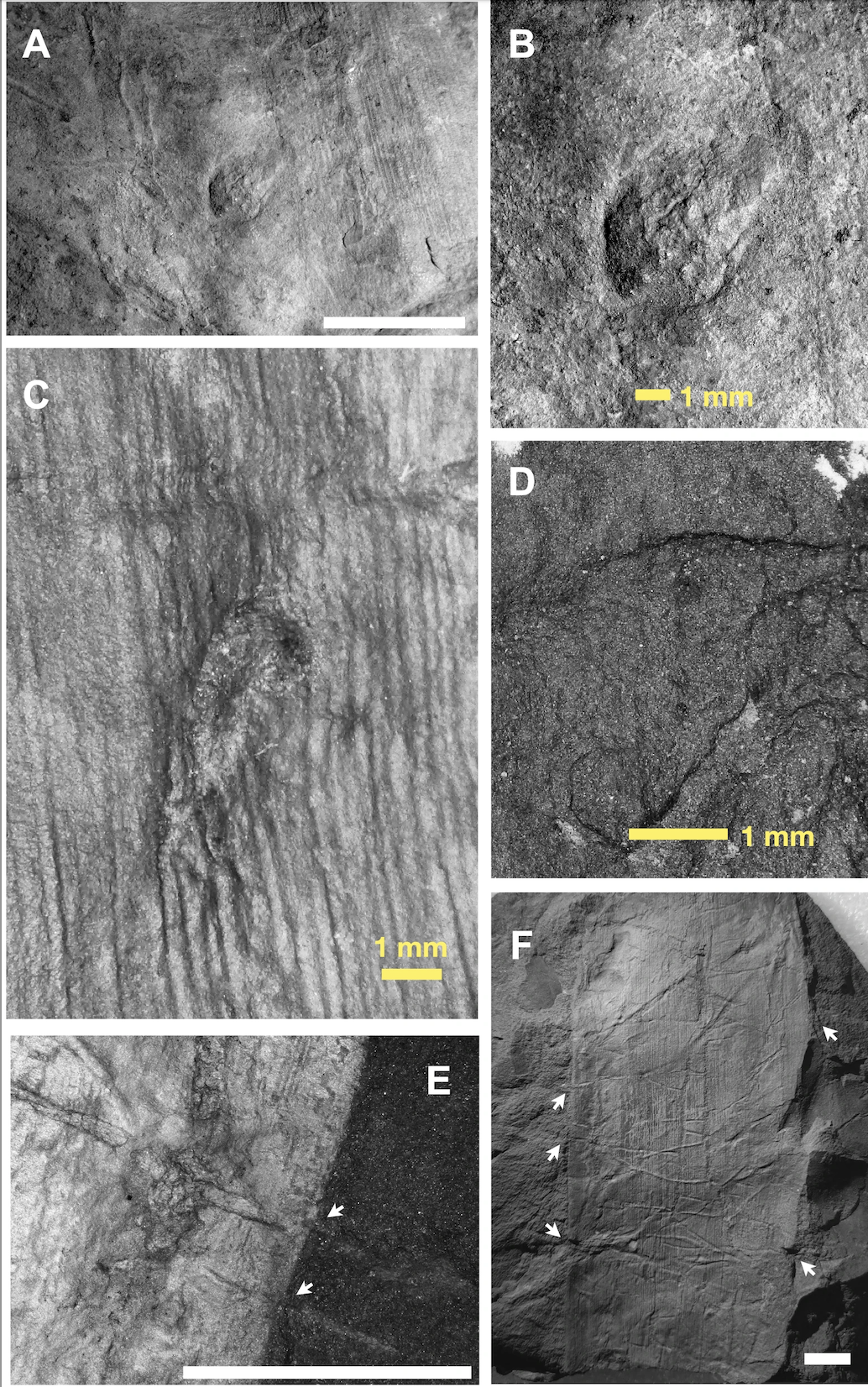

“The exceptional preservation of delicate impressions and traces allows us to reconstruct behaviors and ecology in ways not usually possible with body fossils alone,” says University of Tennessee paleoecologist Jacob Benner, who led the study along with Harvard University paleobiologist Richard Knecht.

“We can see how these early terrestrial communities functioned as integrated ecosystems.”

“The fossiliferous red shale facies may, therefore, represent deposition in shallow depressions near the base of a fan complex that hosted ephemeral or seasonal ponds and pools in which suspended sediment could settle after a flood,” the authors write.

All these years, those layers have held the bodies and imprints of ancient vertebrates, invertebrates, and plants like carefully-pressed flowers kept in the pages of a book.

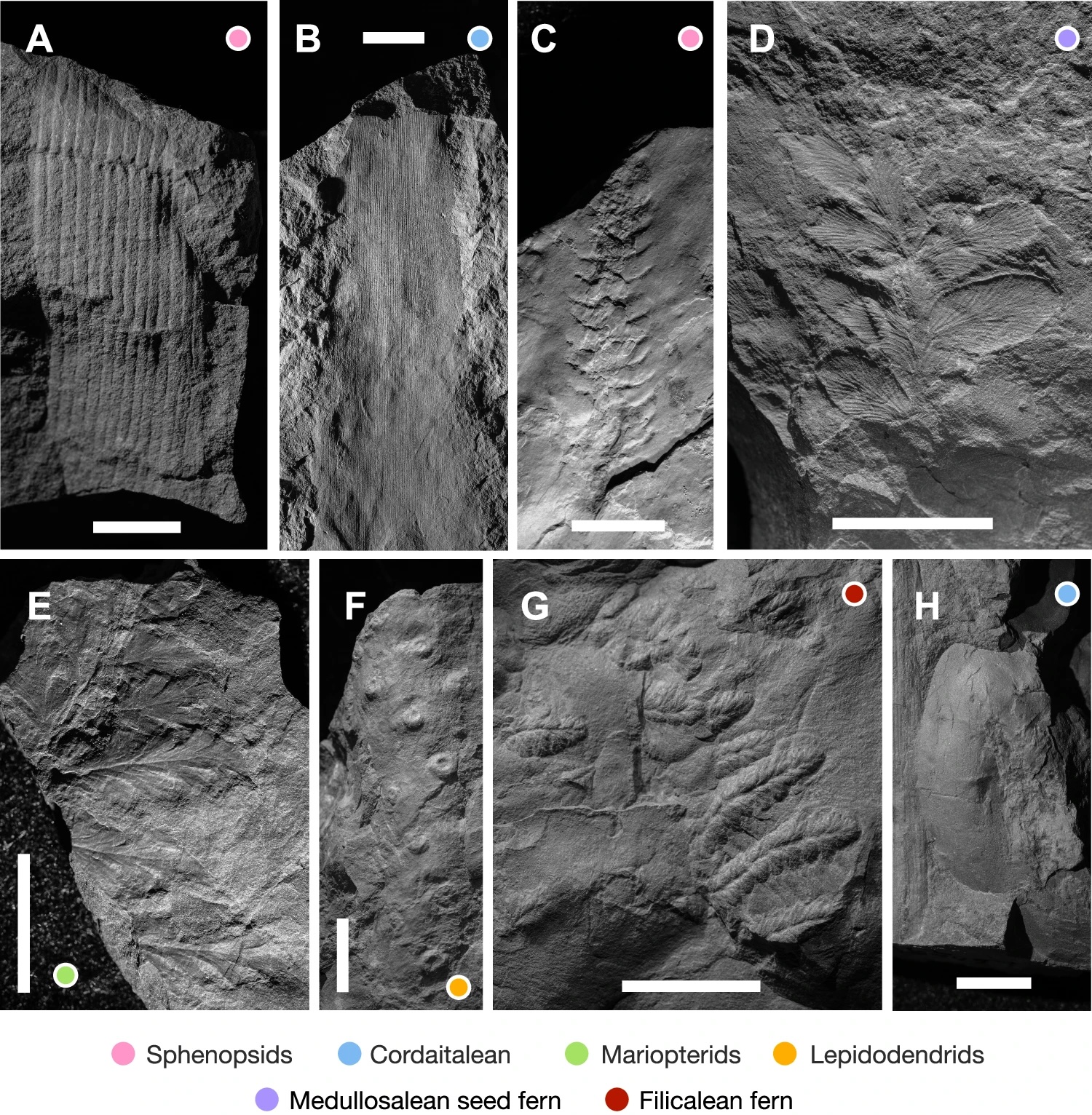

The researchers identified 131 different plant taxa, including 83 unique kinds of plant foliage.

This exquisite find also includes the earliest evidence yet of insect oviposition, in which eggs are laid from an ovipositor into or onto a surface.

The scientists found lesions on a species of Cordaites, trees that grew up to around 30 meters (100 feet) and which may be the earliest conifers. These lesions form when insects lay their eggs on the surface of a plant, and the newfound fossils suggest insects may have begun depositing their eggs in this way at least 14 million years earlier than we thought.

They’ve also uncovered some of the earliest evidence of insect gall formation, in which the insect or its larvae burrow into the living tissue of a plant to form shelter and a food source. The insect modifies the plant’s growth chemically, forming distinctive shapes and bumps on the plant surface known as galls.

This, the researchers say, is one of the oldest documented occurrences of insect-inflicted gall damage in our records.

“We’re seeing evidence of complex plant-insect interactions and some of the earliest appearances of major animal groups that went on to dominate terrestrial habitats,” says Knecht.

“This site gives us an unprecedented look at a terrestrial ecosystem from a crucial time in the evolution of life on land.”

Such a detailed record of this little-known period of time is sure to continue revealing secrets of the early Carboniferous in future studies.

This research is published in Nature Communications.