An ancient skull that was found in Turkey close to a century ago does not belong to Cleopatra’s younger, rebellious sister, after all.

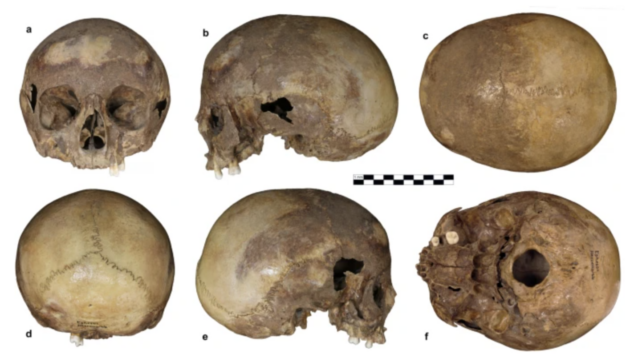

A new analysis of the ancient bone reveals it isn’t even that of a 20-year-old woman. Instead, the skull belongs to a male who died between the ages of 11 and 14 and who “suffered from significant developmental disturbances.”

“What we can now say with certainty is that the person buried in the Octagon was not Arsinoë IV, and the search for her remains should continue,” write researchers at the University of Vienna in Austria.

The modern analysis topples a controversial hypothesis based on a teetering stack of assumptions.

In the year 41 BCE, the Roman politician, Marc Antony, ordered the murder of Cleopatra’s half-sister, Arsinoë IV, at the request of his lover, Cleopatra herself.

Arsinoë had long resisted her sister’s reign, and at the end of her life, she was banished to a temple in a city called Ephesus in what is now Turkey and ultimately put to death.

Flash forward to 1929: a skull is found in the ruins of Ephesus, at a monumental Octagon in the city’s center.

The Austrian archaeologist who unearthed the skeleton assumed it belonged to a special woman around 20 years old, and he popped the skull into his luggage and took it home with him.

Several decades later, in the 1990s, another Austrian archaeologist, named Hilke Thür, put forward a contentious hypothesis based on her analysis of the Ephesus Octagon.

The site, Thür claimed, was Arsinoë’s final resting place, and these were her bones. But where had her skull gone? The rest of her skeleton was not yielding reliable DNA.

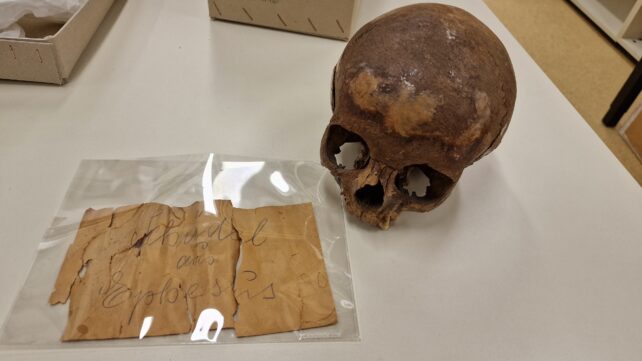

Scientists at the University of Graz in Austria finally rediscovered the missing piece in 2022, hidden within the anthropology archives of the University of Vienna.

In the 1950s, researchers working on the skull concluded it belonged to a 16- or 17-year-old female.

And in 2009, researchers studying the skeleton found the person’s height was around 154 centimeters (5 feet), and they died between 210 and 20 BCE.

Now, however, a modern analysis has drawn a different conclusion.

While the DNA of the skull does match the femur bone found at the Ephesus monument, and while carbon dating does fit the reported lifetime of Arsinoë, researchers say the skeleton is decidedly male. In their new paper, they call him the “Octagon-boy”.

His skull shows conspicuous signs of severe defects and functional issues, according to the team, led by paleoanthropologist Gerhard Weber.

While it’s impossible to say what these issues stem from, they could be related to conditions like rickets or Treacher-Collins syndrome, which is a rare genetic disorder characterized by facial deformities.

Who this young man was and why he was buried in such a special way remains a mystery. Sadly, his skull won’t be able to tell us about Cleopatra’s family genetics, which would have been a huge boon in the famous hunt for her tomb.

“The hypothesis that the Octagon was built in honour of Arsinoë IV is no longer a parsimonious one,” conclude Weber and his team.

“We hope that with our work, the view on Arsinoë IV [becomes] less clouded by anecdotes and speculations, and her and the Octagon-boy’s fate can be unraveled free of bias in the future.”

The study was published in Scientific Reports.